Justin Benjamin is a painter who primarily works out of his studio in New Providence. Most of his painting scenes depict life on family islands he has frequented throughout his life – Eleuthera, Long Island, and Abaco – and his works place the audience squarely in the perspective of the intimate voyeur. In his book Vermeer and the Delft School (2001), scholar Walter A. Liedtke describes Vermeer as “a perceptive invader of privacy.”

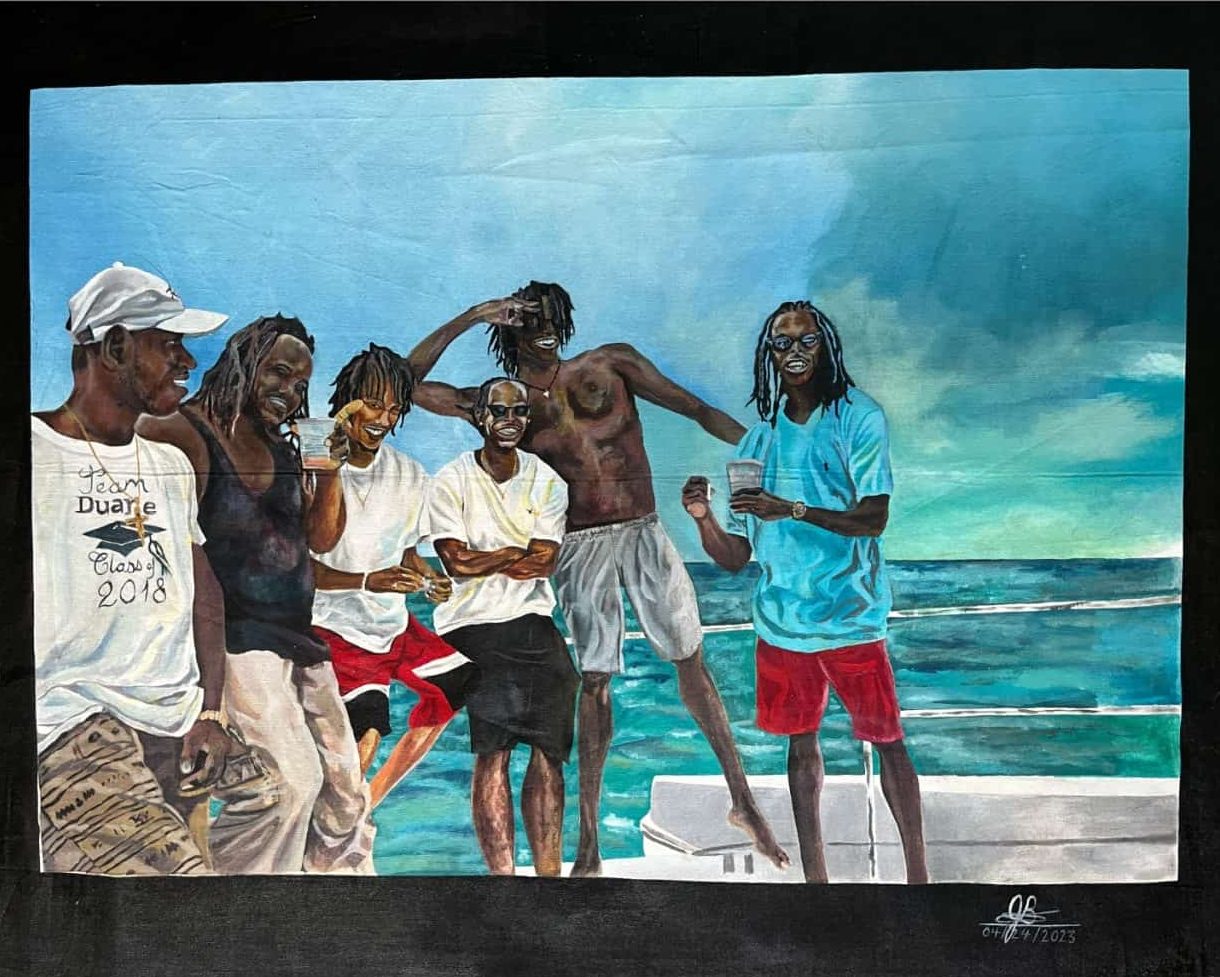

As the intimate voyeur, Benjamin acts as an observer of the unperceived, mundane, or daily happenings of others. Through them, we are witness to the private, secluded life of the locals of the islands, peering through poles and structural cut-outs. The viewer adopts Benjamin’s eyes as the romantic and becomes the first person in his reminiscing, depicting both recent events (such as the never-ending night party in Abaco, as depicted in Just Chilling, or the collection of young men gallivanting on the boat in Do It Again) and reconstructions of memories, (such as the Aboconian marble scene of young schoolboys playing for keeps in Marble Season).

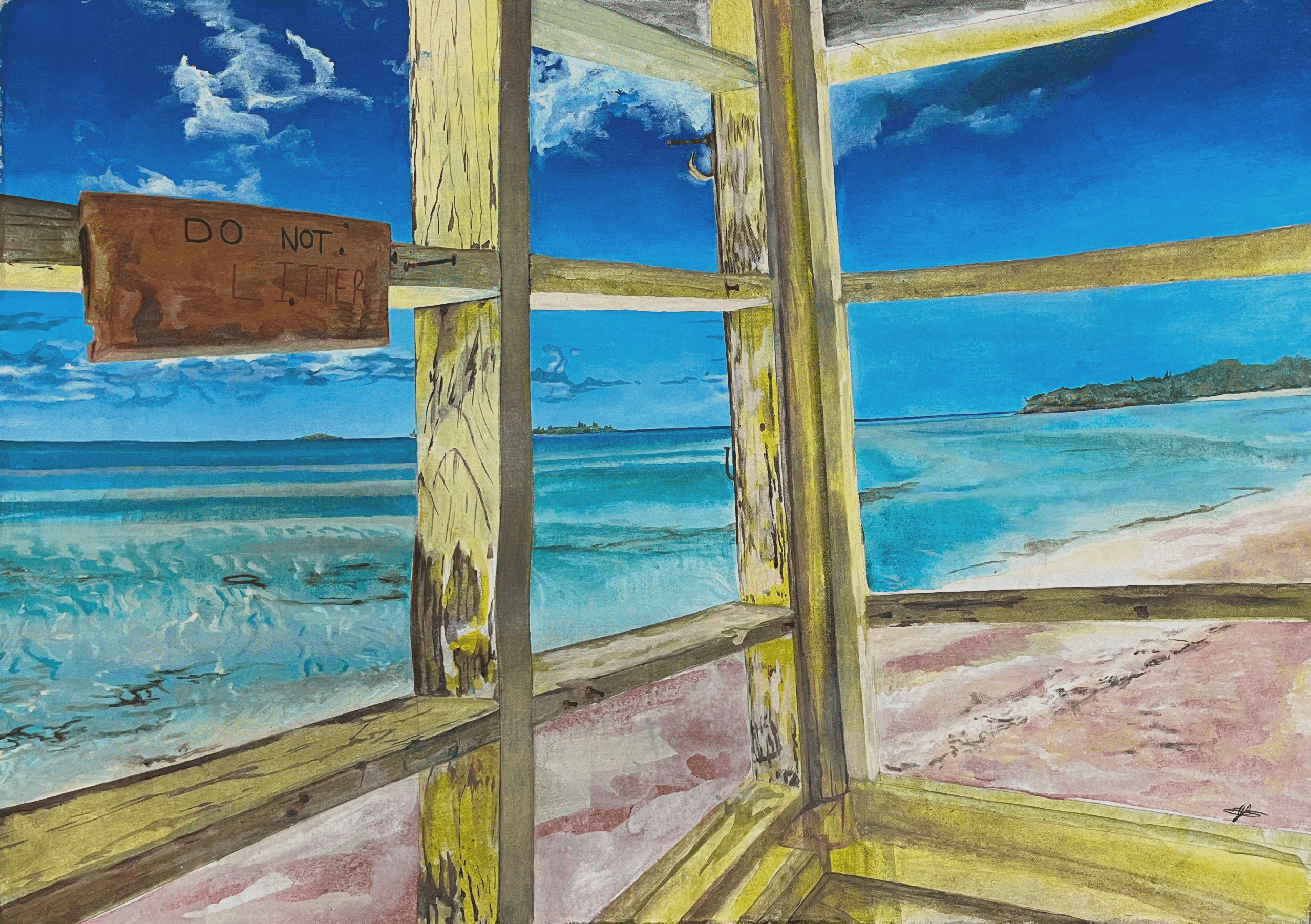

The way Benjamin constructs his compositions contributes to the larger practice of interior composition found in art history. Comparisons can be drawn to Vermeer, who famously tackles aspects of voyeurism through presenting the intimate/interpersonal interior. In Vermeer’s case, the viewer is often looking into a room, indicated by Vermeer’s adept use of depth and by placing windows, curtains, or doors in the foreground for the viewer to look through. Like Vermeer, Benjamin creates this intimacy in his paintings through formalistic construction: often utilising linear point perspective to create planes of interiority. He also does this through physically lowering the audience’s center of view. He utilises the edges of shorelines and boundaries of rooms and walls to create borders that alter the audience’s scope. With this technique, Benjamin envelops the audience into his field of vision, making them an accomplice in his spying, a secondary voyeur. In Keep It Clean, Benjamin not only forces the audience to look through the wooden porch onto a beach, but the depth indicated by the lines following the horizon makes the scene appear even further away. The effect is that the viewer is noticeably not a part of the scene itself, but a visitor just passing through.

This viewpoint, however, is much different than the typical expat romanticist, such as Hildegarde Hamilton or J.F. Coonley, who captured scenes of island living without depicting the intimacy of the day-to-day. Benjamin pulls from his memories and lived-experiences , and this is a direct contrast to an artist who sits and paints the beach en plein air, as if to capture a photographic depiction of the scene, rather than be a witness to the scene itself. With Benjamin’s paintings, he is not only trying to communicate the beauty of the beach, but the experience of being on that beach – and for him, sitting on the porch and looking through the wooden panels onto the shore is what he remembers most significantly about visiting that beach in Eleuthera. Like Vermeer, Benjamin creates intimacy with the audience in Keep It Clean by indicating that we are also in this room, peering through panels, sharing the experience of looking at the subject with him.

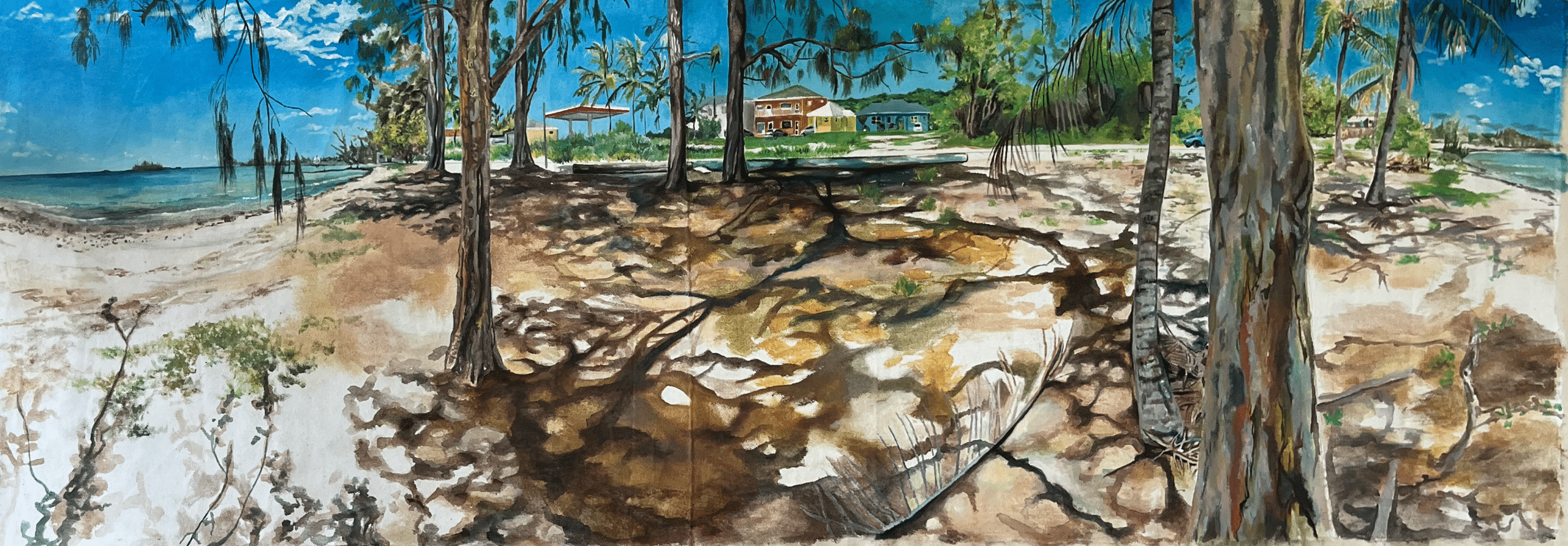

Benjamin’s viewpoint is that of the local, someone who experiences the place they are depicting in a more nostalgic sense, rather than a viewpoint of someone who has traveled here and has a much different relationship with the image they want to communicate to the audience. Thus, his work naturally juxtaposes constructions of an imaginary paradise seen through touristic depictions of the islands. In the typical tourism ad, the local is often relegated to that of a background character or an invisible prop in the landscape. Benjamin’s work, however, not only places the locals to the forefront of his renderings but invites them to remember their own experiences with the scenes that he depicts. In Do It Again, Benjamin showcases a line of black young men soaked in joy on a boat in front of crystal blue seas. In Left Inside Da Car, Benjamin uses a wide sprawling lens to capture not only the shimmering waters but also the island “cityscape” distanced behind casuarina trees. Benjamin turns a recount of the mundane activity of being left in the vehicle, on the sideline, observing another complete their errands, and trails the viewers eyes across this layered landscape of crystal waters, encroaching casuarinas, and dotted buildings with a gas station in the back.

At his core, Benjamin is a wanderer in his own home and creates paintings that reflect this perspective as he travels throughout the archipelago. As he drifts from island to island, falling into local activities and family flings, Benjamin records his own experiences and invites the viewer to participate in these memories with him. Unlike the static picture of some romanticists and the alienation of the tourism ad, Benjamin is a voyeur in the middle of the room, holding a connection with each space he documents. Through his paintings, he creates an eye, a viewfinder for the audience. He places them squarely in his vantage point, inducting them into his activities, ramblings, and the interesting mundane.

Liedtke, Walter A. (2001). “Johnannes Vermeer”, Vermeer and the Delft School, Yale University Press. New Haven and London. p. 161.