“Water: The giver and the taker of life”: Edrin Symonette’s “Salt of the Earth”

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

The University of The Bahamas

Salt: pressed into flesh, brines and cures, drying left on lines, as flies land and enjoy a feast of decaying flesh; a colonial resource extracted from the spaces of the once far-flung regions of empire. Salt is a way of life; a natural resource abundantly available in the islands; the pain of enslaved Africans who laboured tirelessly in its corrosive briny suspension as they raked salt under hot sun. Their skin ulcered, backs bent and minds steeled against the dehumanisation of exploitation and enslavement.

Salt = cultural materiality. The southern Bahama Islands are famous for salt production, given their dry, white heat, scarce water and scrub land coverage, they survive off salted foods and salt production.

Material is significant in art and nature. The historical and cultural impact of material–in this case, salt–resonates on many different levels with people and places in multiple ways. The materiality of art and artistic presentation often coincides with cultural materiality and becomes a nuanced reading of cultural performance as well as (re)presentation.

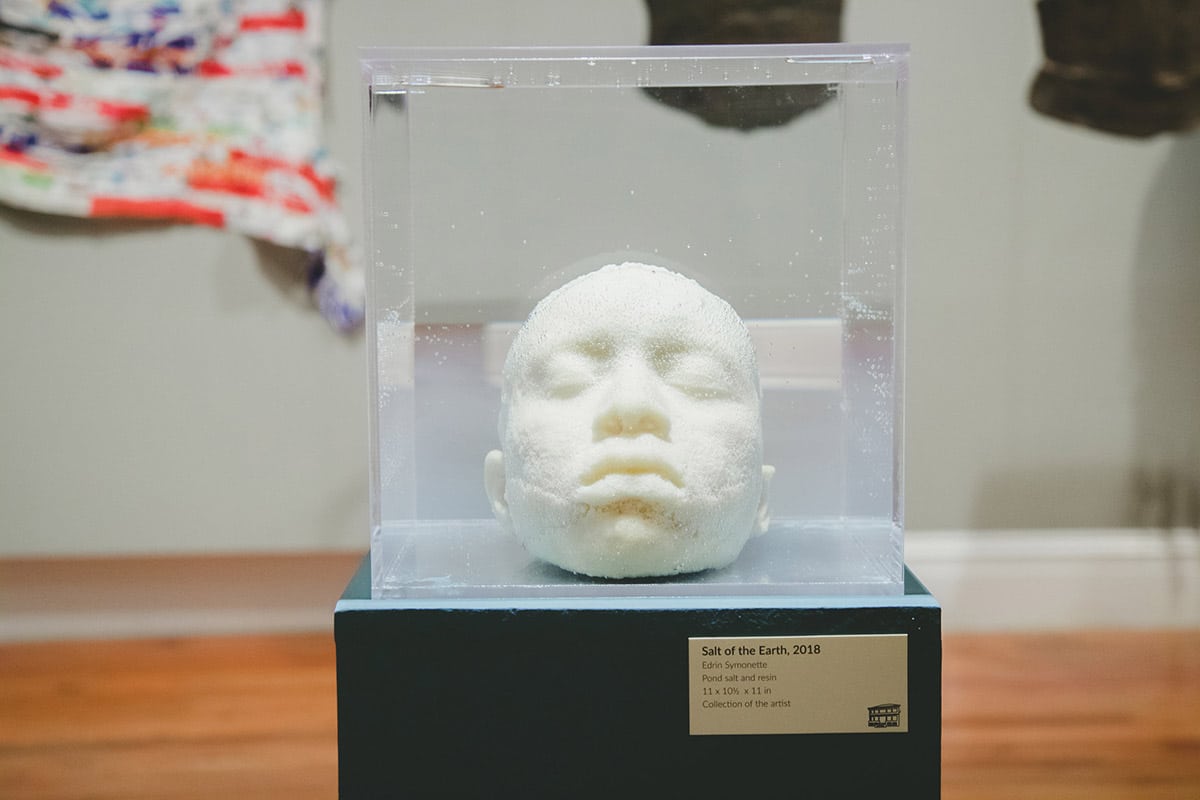

In this case, Long Island-based artist Edrin Symonette undergirds his practice with an understanding of the cultural importance of salt. The material, visceral and cellular, the levels implication of salt in Bahamian cultural and socio-economic identity are deep and penetrating. His most recent work included in the National Exhibition 9 “The Fruit and The Seed” titled Salt of the Earth (2018) presents a head cast from salt and resin suspended in water and enclosed in a clear plexiglass case, which speaks to the value of light and materiality, as well as the sole use of water and salt. As so much innate memory is captured in the physical body that transcends temporal limitations of the here and now into a memory of unlived experiences. The cross-generational pain and trauma of spaces and materials. The water and salt solution become vectors of cultural memory that speak to the dire fear many Bahamians have of water; the unhealthy love of salt that produces unreasonably high levels of heart disease and hypertension, all related to historical realities that continue to haunt, reverberating in physical body as well as in artistic expression.

Salt of the Earth, (2018). Edrin Symonette. Pond salt and resin. Encased in a plexiglass cube. 11″ x 10 1/2″ x 11″. Work courtesy of the artist

The Head

This is a place where thinking, processing and change occur; often the management centre of the body aside from the heart/the two must work together: however, we often find that the power of partnership between head and heart/body is diminished by those who perceive themselves to be more powerful than all others and dominate in ways that scuttle the creativity and longevity of communities and individuals.

Sculpture is often seen as a form of art used to enhance the power of those perceived to be wielding power; we see this especially in work by Michel Foucault and other community and resistance based artists whose work challenges the perception that power is limited to a small group who dominates and exploits as they rule. As Foucault argues: ‘Power is everywhere’ and ‘comes from everywhere’ so in this sense is neither an agency nor a structure (Foucault 1998: 63).

The power resides in this articulation Symonette’s Salt of the Earth a material reality, yet also a spiritual and historical remnant. This undermines the concept that power resides in one place and is controlled by one group, as is so constantly strutted out by the core periphery model we follow. However, all experiences form the idea of a national identity, as Nicolette Bethel points out, there can be no ONE Bahamian identity. Symonette’s Salt of the Earth (2018) brings this home for me as it demonstrates the temporal and temporary nature of identity but also the need to see stories and experiences as equal and diverse, and to diffuse the constant hierarchical nature of nationalism’s place/space-locked identity in a patriarchal historical form. Much work has been done on the history of loss, but little has been done on the reality of social death and the power of diversity in building national identities.

Salt of the Earth (2018) grapples with this discussion.

As power shifted from the colonial governor through the Bay Street Boys to the first majority elected government in the country in 1965, which would be termed Majority Rule in 1967, the idea of majority rule was that people would now be active agents in their own lives. Historically, this was not necessarily so unless one was “white”, landed and male. The decolonial or postcolonial process was sometimes violent and vexing as Black people and other persons of colour were repressed by an oppressive yet paternalistic benevolent state. The concept proved to be flawed as was revealed early on in the development of the Bahamian nation and especially the Bahamian state.

Installation shot of Salt of the Earth by Edrin Symonette. Images courtesy of Jackson Petit and the NAGB.

The Work

Salt of the Earth (2018) breathes a haunting air because of its suspension in the plexiglass case. Freshwater in The Bahamas is a constant struggle, as much as we overlook its precious nature. As children growing up in the 70s, water was usually turned off in the capital. In smaller Out-Island communities, threatened by the progressive move to the capital because the modes of survival and prosperity had been removed, lobbed off by a new Nassau-centrism that led to the eventual death of many small and large Out-Island communities, water was scarce, even more scarce than on New Providence where it was barged in from Andros.

On Long Island and Harbour Island, I remember the need for self-reliance and the strength of community. Government did little or nothing for these places that would only receive the gift of infrastructure after 1992. Generators would come on for a while around sundown and then be switched off at dark or shortly thereafter.

Water is needed for drinking but many people still drown in wells and other standing bodies of water because there is a national fear of water. It is also interesting how Symonette uses these two symbols of life and suffering together to demonstrate how salt dissolves in freshwater, the very life giving medium we need. It is also historically significant the ulceration salt has on black bodies and the same way these bodies dissolve into sores due to hard labour in the salt pans, as Mary Prince discusses in her narrative of slavery in Bermuda and the Southern Bahamas.

The sealed plexiglass case provides an interesting play on visibility and distance between object and self. The water and salt, often used to cure freshly-caught marine life like conch and fish, serves numerous purposes from preserving food to providing financial support to communities that farm salt. The work explores the loss but also the memory of a past built on salt. It is temporary and permanent. The corrosive nature seems somehow permanent as the brine eats through everything from cement to steal and flesh. The physical pain of salt ulcers is extreme, and bones are exposed in individuals who are forced to continue in the salt ponds and flats.

Symonette, though, presents a kind of pun on salt as he explores the physical erasure of the population from the spaces that once thrived. Long Island, similar to much of the southern Bahamas has a dying population. The lack of employment means that people in the productive phase of their lives must leave the islands and move to a centre with jobs, like New Providence, Eleuthera or in earlier times Grand Bahamas, today, another dying community. This erasure is most haunting in its complexity but also its legacy of resilience. Many refuse to leave; they remain in spite of hardship.

When Diamond Salt closed its salt plant on Long Island, it continued the legacy of postcolonial instability through plantation-model one employer communities, where the plantation ruled the roost, followed by Out Island depopulation. This erasure speaks to the need to decolonise and to write anew.

Though beguiling, the trappings of independence really wore off as soon as the parades were done and the flag raised. As the colonial companies left wreckage piled up. The legacies of commercialism and banking have never left as imperial, colonial banks like Barclays and Royal Bank of Canada, much like the Hudson Bay Company, build their wealth from the salt of the earth that would then be trampled underfoot once it lost its saltiness.

Salt of the Earth grapples with the lack of opportunity afforded to the real salt of the earth, the people. The harmful, silencing, exploitative legacies of slavery and emancipation remain intact in such small places where a single employer dominates(ed) the landscape until it is neutralised and then leaves the space emptied of possibilities and embroiled in the stagnation embodied in legal chaos and domination of a (post)-colonial space.

Symonette’s work is so nuanced and materially revealing that one is left speaking to one’s self of a history compounded by corporate occupation. Legacies live in our bodies for generations and even when washed away return in (dis)ease and deformity..