By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett.

Frames capture or remove things, images, objects, people for or from the public eye. The frame of the photo can bring something into sharp focus, or it can reduce that same thing into an abstraction in the fore or background and highlight something else. One image usually metaphorically represents an entire discourse and political, economic and socio-cultural paradigm, a way of thinking about enslaved bodies and their relation to consumer politics, that is to say, discourses of otherness and sexualisation.

What we see depends on the gaze, and the gaze leads us from its vantage point. There is hardly ever a depoliticised gaze. Let us look to the South Pacific with Paul Gauguin’s work. We can also look at the photographic work examined in Dr Krista Thompson’s “An Eye for the Tropics” to see how the frame determines what is seen and what remains invisible or obscured.

The tropics is an interesting construct that relies on a historical power imbalance or racial bias built around Darwin’s and Hume’s theories and development asymmetries. These images that deploy messages are culturally specific and usually time specific, however, they can transcend both culture and time to become resistant or unruly. Catherine Cocks’s “Tropical Whites: The Rise of the Tourist South in the Americas” provides an interesting study on not just the history and links between colonialism and tourism, but also the power of the gaze to continue to frame what we see and how we see it. The focus of the camera and the painting is extremely important to the message held in the frame. Art serves to either build the formalism and the meaning deployed through the work or it can work to provide positive messaging.

Blue Curry. “New Riviera,” an installation and display that was part of Transforming Spaces 2014. Presented at the former Liquid Courage Art Gallery in Palmdale.

In an installation piece in Paris in the shadow of Notre Dame, an artist collective has created a beached sperm whale to draw attention to the plight of whales and the reality of global climate change. The piece is shocking because no one expects to see a life-like whale, beached andbathed in water in the middle of Paris.

[The beached animal—although very realistic—is a replica installed by the Belgian Captain Boomer Collective with the aim of raising awareness of how our society and the way we live is affecting the environment. The metaphor has generated a game between fiction and reality, reinforcing a feeling of disturbance.] (https://www.designboom.com/art/captain-boomer-collective-whale-paris-07-24-2017/)

Metaphor and metonym, whole or part, the art of the real and the art of the unreal, these are all aspects of unreality playing against reality. This week’s piece chooses to focus on the lack of awareness brought to the rapidly transforming yet interesting image and frame as imposed on life in the tropics, to use Krista Thompson’s and Cocks’s title. In work by some artists, we get to see differently, and this difference either empowers or disempowers. The beached whale empowers because it changes the focus of the frame, the gaze, or the eye from what is expected to be there, the Notre Dame and what is out of place, the whale. The jarring presence of the whale may cause pause and initial confusion, but the eye must translate the unexpected into meaning. This way of expressing art of creating thoughtful gaps between the self and the surrounding allows the mind to challenge what is the expected programme. Sadly, most times, we do not challenge the expected. It is expected, and we accept the image deployed. There is always a message. The Caribbean as a palm tree holds a message. The Caribbean as a tanned nubile, bathing beauty deploys another message. Both of these are extremely heteronormative, masculinist and colonial in their rendering and their affect.

Unfortunately, we often expect the tropics to be represented in particular ways, and these ways are framed by the trained eye so that they remain unchallenged, we see nothing wrong with them. Similar to marketing soap or shampoo or even body spray, as could be the case with Axe, the images deploy messages of power over people and power to change.

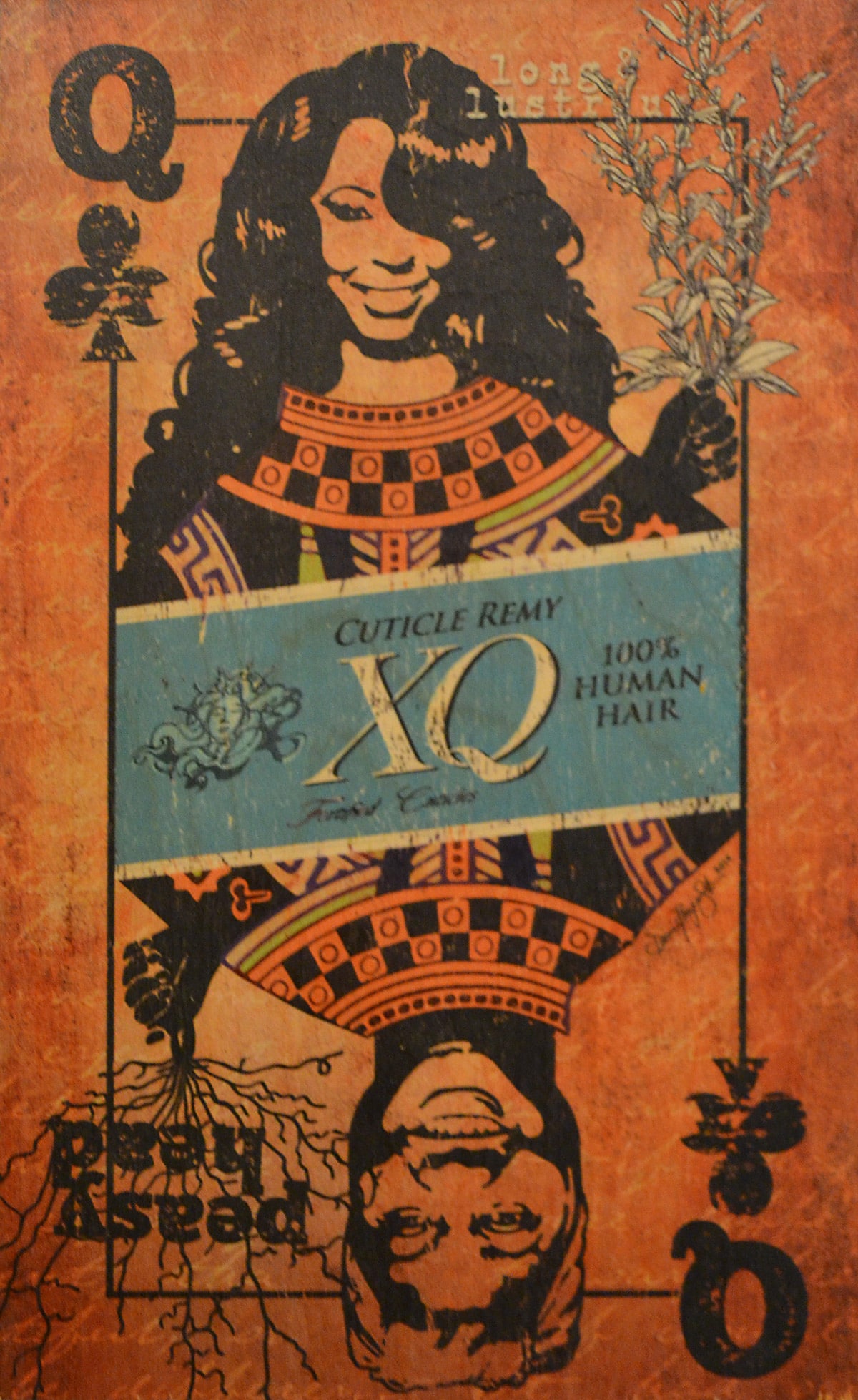

Dionne Benjamin-Smith. “Beauty for Ashes” on view in the Permanent Exhibition “Revisiting An Eye For the Tropics” at the NAGB through March 2018.

The earlier Unilever ads dating back to colonial days were of the effectiveness of the colonizing project to whiten the darkness and to their soap’s cleansing the world of the darkness. This campaign was specially geared towards a warning of the southern latitudes in 18th and 19th centuries where the thought was that if one ventured there as an upstanding gentleman or gentlewoman, one would be corrupted by the lasciviousness and lewdness of the space as everything there was fecund and smutty. So, the image deployed of tropicality was to either promote the need for colonial control over an area of darkness incapable of managing itself or selling that area as a space for sexploitation.

The image has power, and the partnering discourse has another kind of power, so together there is a great project that works to de-civilise the tropics and to reinforce why business must be run from its outsides.

Do today’s arts change this? Cock’s states it thus:

In fact, Tourism in the Southland was frequently described as the trade of tropical joyousness and sensuality in return for temperate business sense, engineering, and, of course, money. . . .(Cocks, 2013 p. 10).

Is it simply ironic that Ministries of tourism seem oblivious to this colonial construct? It is a trade, but it is a Ministry that serves in trading inferiority for superiority continues to cast tourism in this guise.

When we examine art as produced recently, there is always a challenge to the problems with the natives. Dionne Benjamin-Smith’s 2014 work ‘Beauty for Ashes’ showcased in the 7th National Exhibition, and Blue Curry’s “New Riviera” from Transforming Spaces of 2014 would speak to this shift. The Caribbean is imprisoned in the colonial subjects’ understanding of coloniality that continues to hold them and their Ministries in bondage to a frame and a gaze that is hostile to real human development.

Race, as a metaphor for inferiority, as is gender in The Bahamas that refuses to ‘see’ women as deserving of legal rights on an even playing field with their male counterparts is a massive handicap to development. As long as race and gender continue to be defining tropes in the tropical discourse of tourism, human subservience resounds.

Cocks continues:

In the language of race, nature was a realm of dangerous uncontrolled desires; in the language of culture, it was the realm of freedom from oppressive social restrictions on healthy desires. And as they had for centuries, the tropics represented for North Americans and Europeans nature at her most powerful—so, under the regime of culture, the most liberatory. (Cocks, 2013, p. 10)

Dionne Benjamin-Smith. “Beauty for Ashes” on view in the Permanent Exhibition “Revisiting An Eye For the Tropics” at the NAGB through March 2018.

Is it coincidental then that as Cock’s underscores:

In many cases, governments and entrepreneurs bent on resort development seized the lands of poor and nonwhite people suppressed their political participation and political activism. Except as servants, they were unwelcome on the new cruise ships and at the new beach resorts, whose pink-cheeked guests still didn’t want their new liberated daughters to marry one. (Cocks, 2013, p. 13)

Colonialism and the current way governments award contracts and consultancies insist in fact the southern regions are less able to function without the reason of the northern regions:

And the tourist industry reinforced the centuries –old assumption of those in temperate lands–that the tropics ar an inexhaustible source of natural wealth, sustaining economic and political systems that typically benefited outsiders more than locals and degraded the environment. (Cocks, 2013, p. 13)

Black bodies are good enough to be (s)exploited, enjoyed, consumed, but are they good enough to be followed other than through desire? Ironically, tourism has crept so completely into the DNA of Bahamians that they cannot even see where they are being devoured. White supremacy, notwithstanding the racial slurs, sexist rants, bigoted politics and protectionist language, that posits The Bahamas as a mere protectorate of a big, stronger country, being tossed around in the geopolitical centres, has been undone by decolonization and Black power.

On the real side of this dream, let’s say that the installation art as produced by the Belgians in Paris of the destabilising image of a beached whale worked to change the gaze, it may not totally be able to change the gaze or the frame that keeps millions of Southland folks enslaved in a dichotomous language of power.

Dionne Benjamin-Smith. “Beauty for Ashes” on view in the Permanent Exhibition “Revisiting An Eye For the Tropics” at the NAGB through March 2018.

As Benjamin-Smith points out, in as much and as far as it serves Curry’s New Riviera’s desires for nubile, tanned bodies on bleached beaches in a tropical cultural space that ‘they’ own, or at least control economically, usually at the invitation of the local governments. The kind of exchange is not unlike Gauguin in French Polynesia as Meredith Mendelsohn for Artsy noted:

Gauguin spent his Tahitian years with an eye toward the French market, producing paintings, drawings, woodcuts, and ceramics full of tropical clichés to sell at home. He also took three young wives (ages 13, 14, and 14), infected them with syphilis, and eventually died from syphilitic complications at the age of 54 in the remote Marquesas Islands.

Can we hold the government to account or is it us who continue to see ourselves as sexualized puppets for others’ string fetishes? The gaze, obfuscated or guided to see what may be there does not see the (s)exploitation of the 13 and 14-year-olds as Ian Strachan points out in Paradise and Plantation. Our bodies, although ironically controlled by a strongly masculinist, religious, and patriarchal discourse of female disempowerment and male privilege, disarms both men and women. The feminisation of labour in tourism/service industry and the real need to deconstruct and rebuild a better image and frame in which we, as full human beings, can reside, is obvious and dire.

Tragedy: the post-colonial, post-feminist, post-election, post-racist, post-modernist, post-marxist frame has made all of this invisible to the naked eye because we are trained to ‘see’ what may not be there. Let’s look at the art and see what the metaphors reveal to us. However, in a culture and government where the same culture they want to exploit and sell off for tourism is not celebrated nor appreciated nor even protected, we should not expect a whole lot of real cultural support or buy in for the arts as a real and meaningful way of life and economic driver. The stubbornness is the inability of the administration to rid its frame, change it gaze and liberate its eye of the old colonial optics of bygone years. The Bahamas must for Bahamians be, and not for those who enjoy the tourist gaze of the image as deployed by adverts that paint a beach and a body thereon.