We are not used to seeing ourselves outside of the lens of tourism as Bahamians.

This is troublesome for a newly-independent nation not yet 50 years old, and with 200 years of tourism weighing in above our heads. The decolonial work of imaging ourselves as Bahamians (particularly as Black Bahamians) is slow-going but gaining more visibility. The representation for many of our Black non-Bahamian people of this nation is in a more dire state.

These observations and lines of questioning are brought to the forefront in Kachelle Knowles’ delicate and tenderly draughted portraits of the Black Bahamian man in her body of work for Bahamian Man Since Time, which recently closed in NAGB’s Project Space. In the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian and its painful shifts and turns – and in the museum’s efforts to respond appropriately to hurricane efforts, we wanted to share some words on the exhibition as it became the site of a donation center for Equality Bahamas and Lend-A-Hand Bahamas. These works were the backdrop to so many of your efforts to assist and to be supported.

Knowles holds a Bachelor’s in Illustration from Emily Carr University of Art & Design in Vancouver, Canada. Being one of the few people of colour on her course – in a major city with only 1% of its population being Black – she was keenly aware of the ways she was othered and marginalized as a woman of colour, and an emigrated one at that. She was also an anomaly within her course as someone who was actively asking and provoking her lecturers to consider the ways she could and should work as an illustrator producing work for exhibition display – not just on the page. She was a misfit, didn’t quite follow the intended path, and this nonconformity and observation of social positioning is at the foundation of her practice.

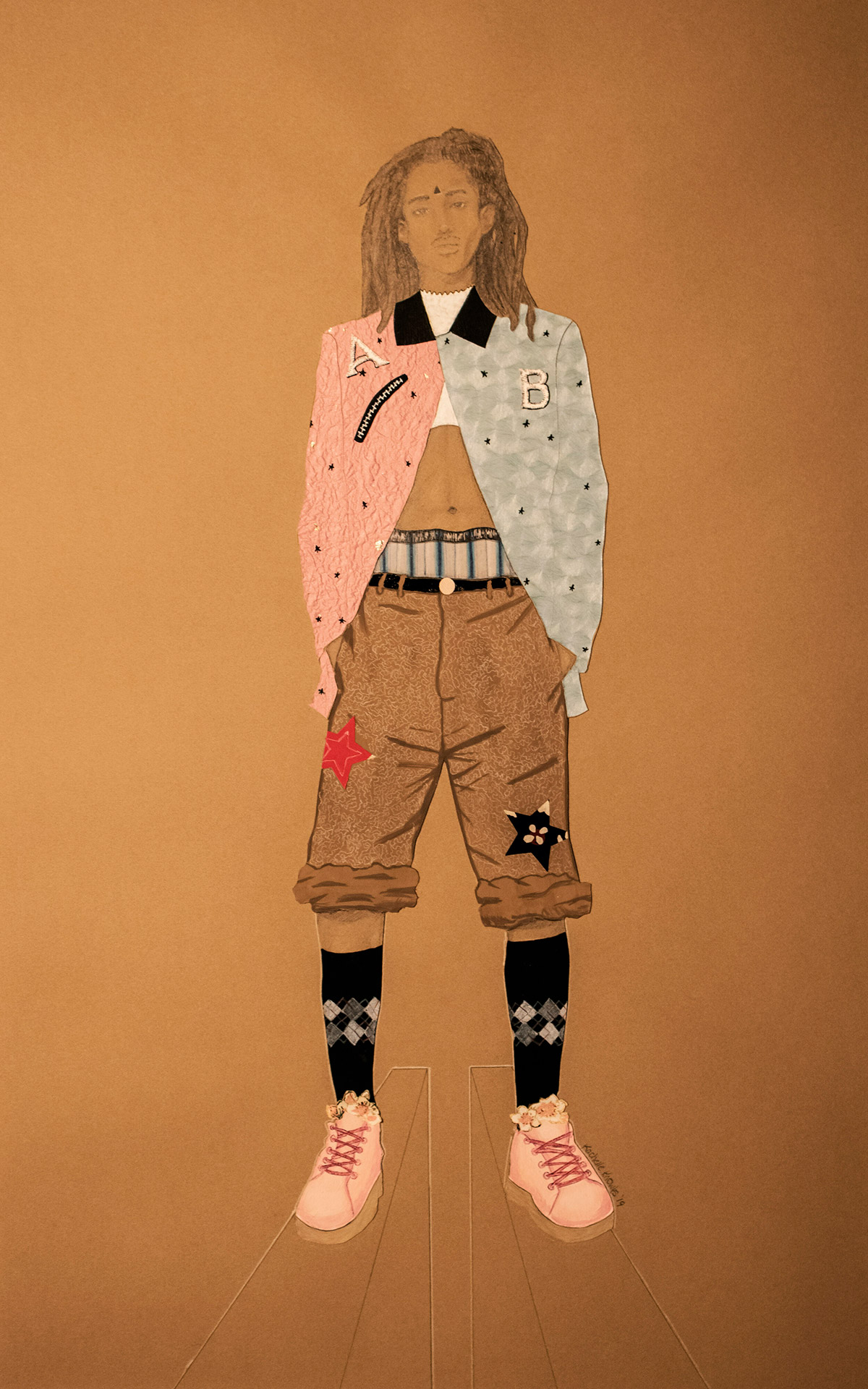

Bahamian Man Since Time is rooted in her own experiences as a misfit of gender norms. A self-identified “tomboy” growing up, she felt most comfortable around the boys and men in her life, and the various figurations we see – frankensteined from faces of the people she knows and the Black figures she searches for online in a facial remix – are testaments to the different ways men have expressed their masculinity. Tight jeans, a shaved head with a seemingly arbitrary patch of longer hair growing out proudly, a suspiciously long pinky nail, gold teeth and elaborately patterned fabric – these aesthetic decisions can seem androgynous or flamboyant to some, and the most utterly masculine to others. It also helps us to document a moment in time, when these trends are ongoing, to be recorded for future discussion much like the Over-The-Hill photographs of Antoine Ferrier, Sanford Sawyer and their contemporaries.

Her work is a play on Bahamian masculinities, but also harkens back to our wider Caribbean sense of masculine social coding. The title Bahamian Man Since Time takes on a stark sort of contention in our current moment of Bahamian nationalist, anti-Haitian sentiments as plans to deport survivors come into the post-Dorian conversation. She is also speaking into wider conversations on the Black masculine figure. Her draughtsmanship and social focus follows nicely into the work of the late, great Charles White – American artist, activist, and general Black superhero. The simple brown paper she uses in these drawings-meet-collage give commentary on the colourism toward Black communities and the “brown paper bag test”, and the work of Dominican-American artist Firelei Baez that delves deep into that underbelly.

It is also worth noting that her solo exhibition came together in the brief calm before the storm that would change our nation’s history forever, and true to her sentiments in investigating the fluid coding and futility of gender, and it’s ever-shifting nature, she shifted her body of work and focus to adapt the exhibition to match the hurricane efforts by producing a series of prints for sale for relief initiatives. Artists work as people in transition constantly and adaptability is the name of the game. It is a pleasure to see the response by artists like Knowles and others within the community is as heartening as the care she puts into rendering Black faces. We find ways to not only represent our collective, but to feed back into it when it needs it most.