Timelines: Developing Blackness

Blake Fox · 8

At the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, our Permanent Exhibition (PE) is up for approximately one year, after which the theme is changed. The upcoming PE will open under the title Timelines:1950-2007, and primarily draws on work from the National Collection and supplemented by work from the collections of the D’Aguilar Art Foundation and the Dawn Davies Collection.

TimeLines will survey significant milestones in Bahamian art history and culture from 1950 to 2007.

Included in the exhibition are photographs that were once a part of Developing Blackness, an exhibition held at the NAGB in 2008, curated by Dr. Krista A. Thompson. It featured studio photographs by Bahamian photographers Maxwell Stubbs, Antoine Ferrier, Sanford Sawyer, and local historian, activist, and dentist, Cleveland Eneas, taken in the Black communities of Bain and Grant’s Town, commonly referred to as “Over-the-Hill.” Aptly named, these photographs show us a period in our history where Bahamians were pointedly claiming and embracing their Blackness. This sense of pride was born out of, but not limited to America’s expressions of Black power during the Civil Rights Movement, the road to Majority Rule in 1967, and The Bahamas’ independence in 1973.

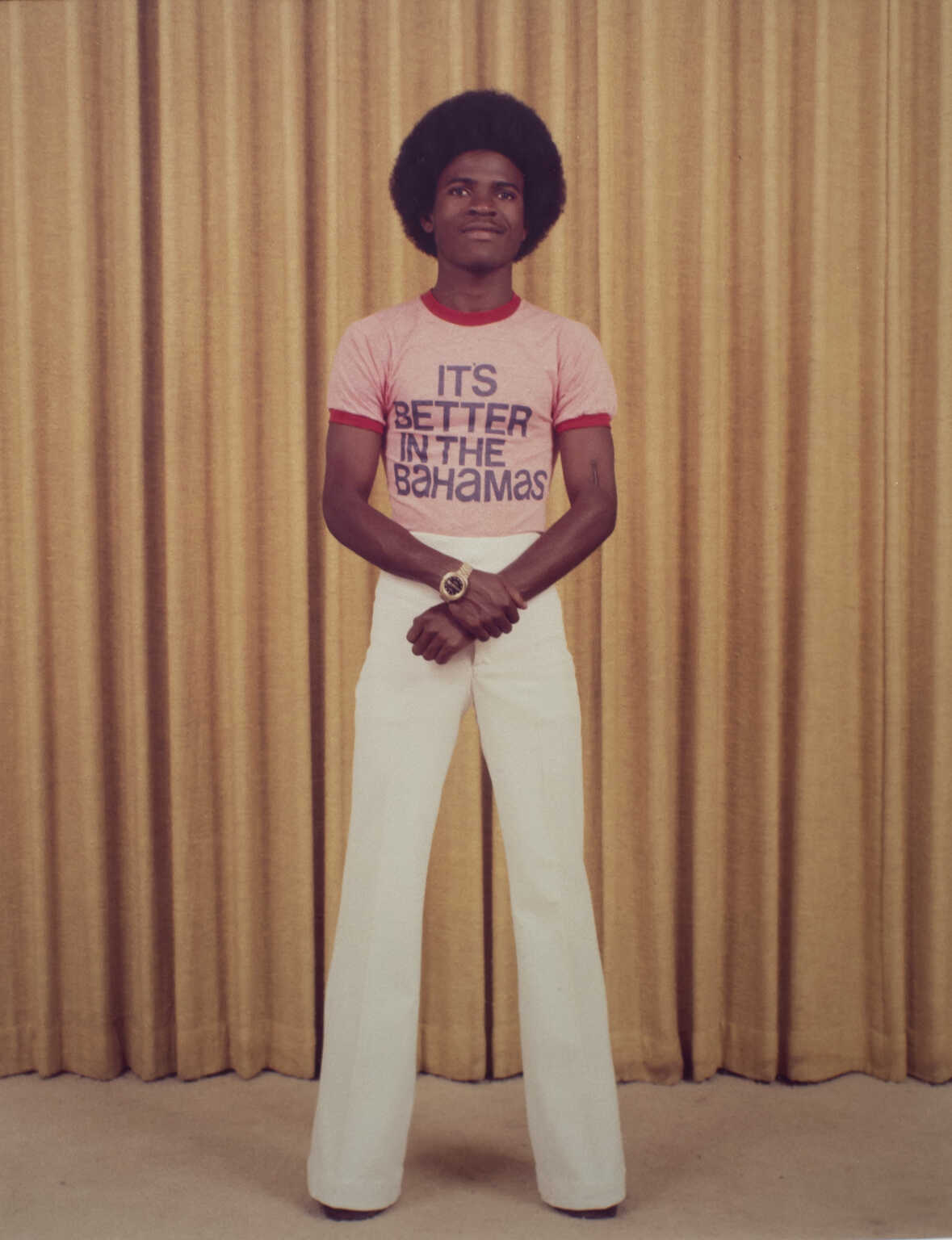

Sanford Sawyer’s photographs feature Black men, women, and children from distinctly different walks of life. There is a marked consistency to his work: his subjects were invariably dead centre of the photograph, with a heavy gold or green curtain backdrop that’s so unassuming that the subjects become remarkably striking. As Dr. Thompson noted in her curatorial essay, the curtains don’t give us much context of location, leaving it up to the viewer to imagine the many possibilities of where these subjects could be standing. The colors of the fiber and Lambda prints are rich, deep, and contrasty. An untitled fiber print from 1978 by Sawyer presents a Black Bahamian man proudly standing in a symmetrical pose with his arms crossed in front of him. His afro is thick and perfectly round, he’s smiling and his chin is tilted upward, he’s wearing an impressive pair of white high-waisted bell bottoms that touch the ground and hide his shoes. Most importantly, he’s wearing a red t-shirt that says “It’s Better in The Bahamas.”

Now fast forward to the digital era where the hashtag #TheBahamasisNotaRealPlace is currently being used to express discontentment and even disbelief with the state of affairs in The Bahamas. Perhaps it was sparked again by the electrical load shedding by BPL during these past several weeks, resulting in lengthy power outages which have rightfully infuriated Bahamians. Moreover though, because the government lacks an overall vision for the country, younger generations specifically feel less inspired and more dubious about our future as a country. The Bahamas doesn’t feel like a place where they are valued. It doesn’t feel like home. It doesn’t feel like it’s actually “Better in The Bahamas.”

I think it’s fair to assume that we are familiar with the quixotic slogan “It’s Better in The Bahamas” coined in the early 1970s by the Ministry of Tourism which has pervaded the tourism industry since. It has become so ubiquitous that it often sounds like a regurgitation rather than a true statement. This phrase is catchy and has proven to be commercially viable, with airlines and travel companies using it for marketing purposes, as well as it being plastered all over t-shirts and souvenirs for tourists to carry back to their homelands.

Yet, there is something hazy and escapist about the phrase, painting The Bahamas in a glistening light that in reality is less pristine than we would like to admit. Undercurrents of colonialism, plantation-driven capitalism, xenophobia, and the like still persist in The Bahamas today.

The Bahamas is often viewed with a paradisiacal gaze, making life here seems so idyllic from the outside. Yet, this isn’t the authentic experience for the majority of Bahamians: a lack of vision in the government, issues of gender inequality, a lack of diversification in the economy and the list goes on, clouds and corrupts this rendition of paradise. Certainly, all countries experience similar issues and their own set of unique issues, but it’s important that we don’t deny our problems without being critical of ourselves.

The proliferation of the aforementioned slogan also indirectly broaches the topic of commercialisation and commodification in art. Sometimes art can be brought into question when it seems to be strictly for financial gain but lacking a meaningful concept. Understandably, a big part of the commercialisation of art is practicality. Artists want and need to market their work, they want it to be successful, and they of course need an income to continue developing their practice and invest in their livelihood. One could argue that certain strides in Bahamian art such as Tamika Galanis’ Lignum and Tingum shirts, Angelika Wallace-Whitefield’s Hope is a Weapon public project which was spawned from the National Exhibition 9 (NE9), and John Cox’s this is how much I love you project make art accessible to a broader community while simultaneously addressing deeper social, cultural, or personal artistic themes. Such projects are a way of responding to and being critical of our current cultural climate in The Bahamas.

Sanford Sawyer captured moments in our history through his photography, moments that we will never experience again, and they give us an eye into the social and cultural context of those times. Similarly, Tamika Galanis’ Lignum and Tingum shirts and Wallace-Whitefield’s Hope is a Weapon project will also become a part of our history.

TimeLines opens on 23 July 2019 at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas and is curated by Assistant Curator, Richardo Barrett.

Blake Fox is an artist, art educator, and cultural worker from Nassau, The Bahamas. He has worked in the visual arts for over 5 years, where he’s held a creative practice and facilitated educational programs. His photography has been featured in international publications and he has exhibited at the Pro Gallery, Popopstudios ICVA, the Project Space at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, the Island House, and TERN Gallery. He is interested in art and museum education as agents for social change.