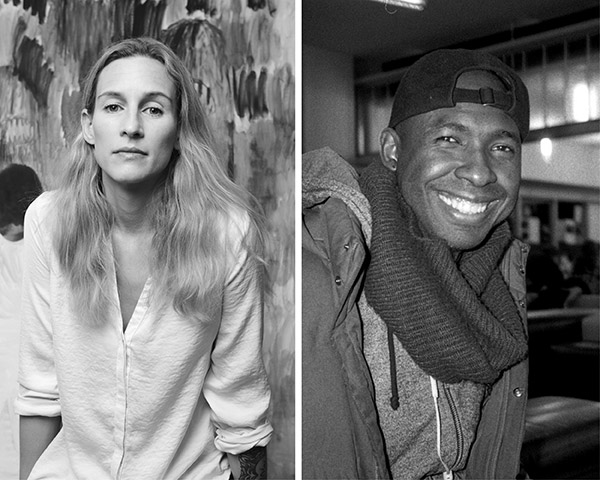

Beauty and Loss in Tessa Whitehead and Chan Pratt’s Work: A Death Foretold, yet Not Dying

Ian Bethell-Bennett · 20

Beauty, as we began two weeks ago, heals souls and allows us to come to a higher place where we feel more human, connected, communal, and loved. Nature, green trees, and shade along roads allow us to walk in and explore the special areas and spaces around us. This exploration is seen in Jean Rhys’ novel Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), and in Tessa Whitehead’s work, the creek (2018) as beauty envelopes us in its natural form. When cement covers every inch of land, the soul is taken out of life. Singer Gloria Estefan’s “Mi Tierra” (1993), similar to Coulibri, the main location in Wide Sargasso Sea speaks of the loss, longing and nostalgia for a home that we have lost the deep connection to and the healing that comes from revisiting even if only metaphorically, metaphysically, or through imagination.

Imagination is the space that creates possibility and promotes personal and community healing and development. Yet many imaginations are killed through infertile spaces whereas Frantz Fanon and Paulo Freire write, the oppressed are sown into spaces of underachieving. The vanishing present is a good place to start a discussion around healing through identification and belonging, a trauma that is often disallowed far too many people. Jean Rhys’ novel Wide Sargasso Sea much like Tessa Whitehead’s work especially Portrait (2019) and Sydney gets married (2018) speak to nature and the relationship between the human and nature, tropical fecundity.The beauty and harmony seep through and into the soul. As Rhys’ main protagonist Antoinette begins to explore her self; she also explores her surroundings:

“I went to parts of Coulibri that I had not seen, where there was no road, no path, no track. And if the razor grass cut my legs and arms I would think, ‘It’s better than people.’ Black ants or red ones, tall nests swarming with white ants, rain that soaked me to the skin – once I saw a snake. All better than people.”

The Duality of Nature

Treasuring the natural beauty is clear, but while this is Antoinette’s perspective, Rochester’s view of the place is totally different:

“There was a soft warm wind blowing but I understood why the porter had called it a wild place. Not only wild but menacing. Those hills could close in on you […] Everything is too much, I felt as I rode wearily after her. Too much blue, too much purple, too much green. The flowers too red, the mountains too high, the hills too near.”

Rochester’s too much is Antoinette’s acceptance. and poignancy Estefan sings about we see in Whitehead’s paintings. It is almost like a manifestation of the imaginary.

“Our garden was large and beautiful as that garden in the Bible – the tree of life grew there. But it had gone wild. The paths were overgrown and a smell of dead flowers mixed with the fresh living smell. Underneath the tree ferns, tall as forest trees, the light was green.”

These words, descriptions of overbearing nature and deep menacing presence compared to self-discovery through exploration and the disappointment of marrying and falling out of love with Rochester, Antoinette feels the first death. As her name is changed, she is separated from herself, yet such separation allows her to be saved but the saving is an actual death at the hands of misogyny itself.

Whitehead’s work brings to the fore all this angst in such wonderful and fading ways as the figures are almost vanishing into the wildlife around them, it speaks to a death foretold, yet not dying.

Pratt’s landscapes speak to the biblical beauty, the fecund nature of the garden in the Bible, but here in the Caribbean, where according to the representation of the male view, only uncivilized things prosper, where the tree of life lives. The tree of life is emblematic of life and nature themselves and speaks to such whimsical and profound beauty and connection. Nature provides a space to heal the losses imposed by colonialism and the distortion of the self-view imposed thereby.

In a recent United Nations Report on Biodiversity states: “We have reconfigured dramatically life on the planet,” report co-chairman Eduardo Brondizio of Indiana University said at a press conference.The loss of biodiversity speaks to the lack of love for and disconnection from beauty and nature Rochester shares. This is at work in the novel and I find it hauntingly present in Whitehead’s work. It is distressing, yet calming to see the separation but the deep connection between the beings presented in the work and the natural beauty they are held in and by. It is life: the beauty of the ocean, the deep blue and deep turquoise, that like the deep greens transport us to more human places in us. Yet we choose to destroy that relationship.

How Do We Heal?

Art and writing heal. Music heals. Connection with kin and culture heals. Perhaps this feminist understanding of searching for warmth that Bertha Mason looks for as she sets the mansion alight is the warmth of the Caribbean Antoinette misses, as she is separated from herself by the man who has come to be no more than an exploiter. The texture and the shadows speak to the written description of the beauty of the garden at Coulibri that resonates with Alejo Carpentier’s The Lost Steps, 1953. The steps are lost, the separation we feel is real, but this can be undone through healing practices. The practice of writing, as Rhys or Virginia Woolf shows, does not align with the male experiences but shows an entirely unique version of life altogether.

Whitehead’s play with light, dark, shadow and texture, longing and disappearance are all those notes that appear in the text with the cleaving off of limbs as Antoinette feels as she is taken to England, a place she has learnt is salvation. The color, tone, and texture in Pratt’s and Whitehead’s works bring the beauty of Rhys’ words in the majesty of the present, even if it is vanishing as The UN Report on Biodiversity warns. These works are reminiscent of Edwidge Danticat’s The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story (2017): the beauty and the longing, oh so so incredibly touching and wonderfully healing for the soul.

Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett is a Bahamian academic and creative whose work explores Caribbean migration, displacement, and identity through photography, poetry, and critical essays. Influenced by thinkers like Gloria Anzaldúa and Édouard Glissant, he examines colonial legacies, gentrification, and the privatisation of public resources.