Climate Refugees: On Becoming Climate Refugees or Building Back Differently

Ian Bethell-Bennett · 16

After Hurricane Irma hit Ragged Island in 2017, that island was declared uninhabitable given the loss and damage to this small island in the Southern Bahamas.The community was told it would be the first green island in The Bahamas. From this tragedy, grew an initiative to explore how we could rebuild better and retain the lifeways of the small community on Ragged Island.

Hot Water was an exhibition under the wider project of the Double Dutch series at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) in August 2018 that drew on best practices and the work and ethnographic research conducted on the ground in Ragged Island by faculty and students of the University of The Bahamas and members of the arts collective Plastico Fantástico. The work has continued on the project, yet government’s words have vanished into a boiling sea of tsunami waves.

The art of living in the tropics was some of the writing derived from the research and documentary that supported the show. We find now that the art of living in the tropics has continued and needs to be a sustained topic of a dynamically changing conversation: how do we retain life in the tropics, become refugees to climate change and flee the islands we inhabit? As the sea levels rise around barely sea-level islands, we face new threats to our existence. As the climate crisis advances, which includes rising temperatures as well as more severe storms, we see the increase in hurricanes or mammoth storms that come through annually during hurricane season.

The last 5 years have shown us that consecutive storms have grown in strength, ferocity and rapidity of formation, yet many remain, like the proverbial ostrich, with their heads and their preparations firmly stuck in the sand. This is not unique to The Bahamas, though other places are quickly learning that their blindness has been dangerous and have begun put on 20/20 vision workers.

Climate refugees are a 21st-century reality just as much as natural disasters and conflict refugees are a reality. Given the political and social dysfunction entrenched in much of post-colonial-state structures, we are constantly being undermined by the lack of consultation and indeed regard by government and agencies for the well-being of the citizens.

In this regard, the Small Axe initiative currently on display at the NAGB, The Visual Life Of Social Affliction (VLOSA) is a unique partnership to this discussion on falling away off the shores of tiny sand bars and deeply threatened islets. Only, in this case, these are the second and third largest economic contributors to the Gross Domestic Product and to Bahamian Life in general terms.

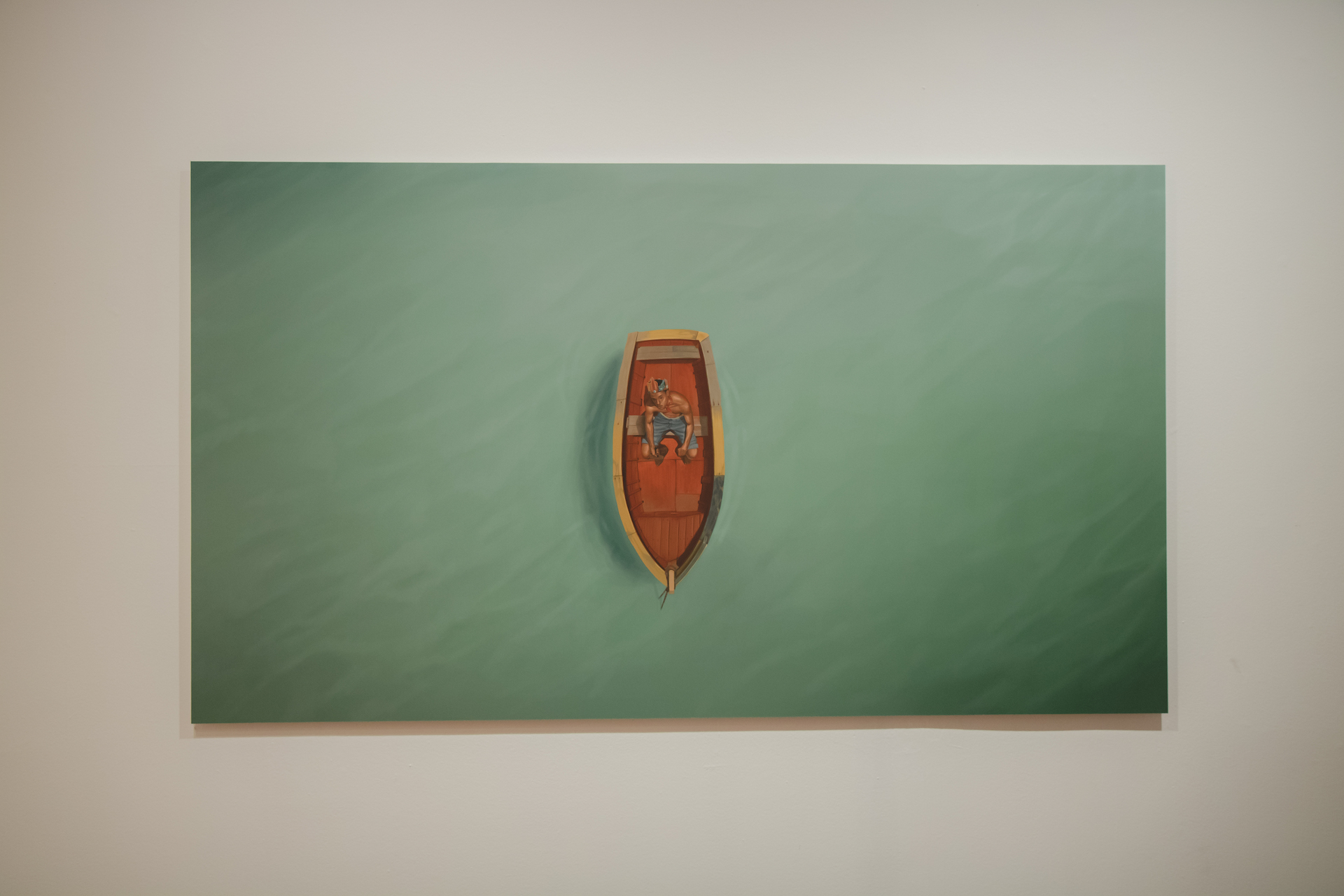

Jamaican artist Ricardo Edward’s Pirate Bwoy (2018) captures our nuanced existence between a new reality and old thinking. At the same time, it underlines the corruption of representation and governance. As BPL continues to plunge everyone into darkness daily because of its corruption and mismanagement, as well as poor planning, and this is not isolated to New Providence; it occurs throughout the inhabited islands of the archipelago. The oil seeping into the waters off Clifton Pier and now Grand Bahama speak to a fictive narrative that reports no environmental damage through the continued exploitation of fossil fuels to produce energy to power Bahamian lives and, now, deaths.

Professor and art critic, Yolanda Wood notes in the catalogue for the show that:

“The sea where the pirate boy’s boat is anchored is neither the paradisiacal turquoise blue of touristic images nor the tenebrous, ferocious sea that devours illegal migrants, subjects–both of them–very frequently represented in insular artistic imaginaries” (59).

We are being shown the art canvas of watery graves and tsunami power as communities lay in tatters under ocean incursion into in-land, flat towns, and the coastal erasure. To date, the narrative has been skewed in negative ways that need to be adjusted. This is not God striking us or cleansing the earth, this is climate collapse/global warming and governmental corruption coupled to make serious disasters deeper and wider than necessary. For us left in The Bahamas to recover, our recovery is delayed by the trauma of darkness and dysfunction.

As the NAGB opens its space to healing workshops, and as a sanctuary under the mental health-focused campaign “We Gatchu: Sanctuary After The Storm” for those afflicted by and after Dorian, we need to think about how we participate in the narrative and art of survival. Living in the tropics is changing. We have been produced for tourist consumption as the resorts sit on top and sometimes literally in the place of the plantation; we need to redirect our lives to refocus on community empowerment and rebirth. What happens if an entire community has to leave?

We see this now in Marsh Harbour, Abaco. Wood notes again on Edwards’ work and his thoughts:

“Imagine being stranded at sea and the only resource you have to survive is a gun. YOU DON’T. It’s the same thing when you’re stranded in the ghetto.“

Wood’s essay is deeply disturbing as it uncovers the layers of climate refugee status, I see as parallel in our current situation. As we are charged sometimes thousands of dollars to evacuate the Dorian ravaged lands, we are told that these first hand accounts and stories are not true by the government. Wood notes “The piece is a proposal inviting decipherment, an image of solitude made even more disturbing by the age of the figure represented among the potential victims, the most vulnerable group in the existing social order that produces its effects of exclusion and marginality. In the semantic field of afflictions, the work emits a silent scream that has the value of social criticism” (59).

The landscape of Abaco is not habitable. The stench enters every pore and the heaviness of death suffocates in the heat. Marsh Harbour is ravaged and torn. I have not been to Grand Bahama, but I imagine, again the need to imagine/image something, it to be similar though different from Abaco. We must now re-imagine ourselves and regroup as we struggle through climatic cataclysmic events.

Edwards’ Pirate Bwoy captures the marginality of the people caught in the storm and threatened by extinction through non-planning and governmental environmental corruption and destruction. The Visual Life Of Social Affliction provides an interesting moment to experience Dorian through art and the open space to community healing at NAGB speaks to the need to bring in and shift the mindset of those most vulnerable in our society.