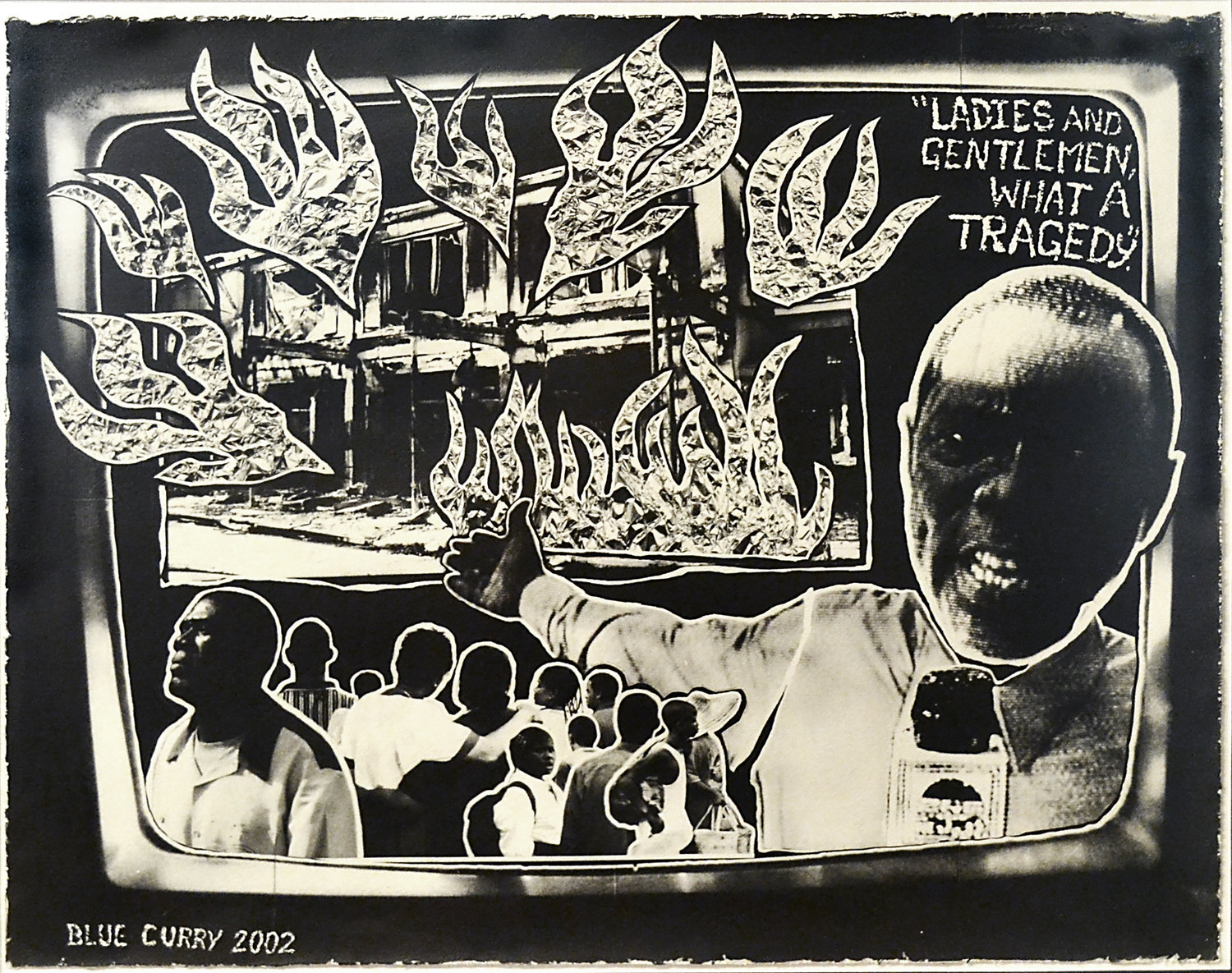

Curry’s gamut of work usually involves some form of tongue-in-cheek critique of the tourism culture of The Bahamas, but this earlier work which stands in the National Collection from 2002 deals more with public response and representation than tourism as it is. The link is still there of course, as the Straw Market on Bay Street has been well known as a spot for tourist consumerism since the 1800’s, with the particular branding of the space that we know today coming out of a revamp in the 1920’s. Previously, however, the site was used as a market of a different kind, to process enslaved Africans to be sold later at the Vendue House.

All posts tagged: Collection

From the Collection: Dave Smith, Let Us Prey, 1984-86

By Natalie Willis. The title is undoubtedly provocative given the Bahamian bent toward Christianity, but “Let Us Prey” (1984-86) is, quite literally, a gift. Donated by Dave Smith in 2007, the work is at once an act of good faith, while simultaneously critical of bad. It’s another painting from the National Collection that we have given some gentle care to and put on display for the current Permanent Exhibition, “Revisiting An Eye For The Tropics,” and fits into the theme of the Bahamian Everyday that works within this exhibition.

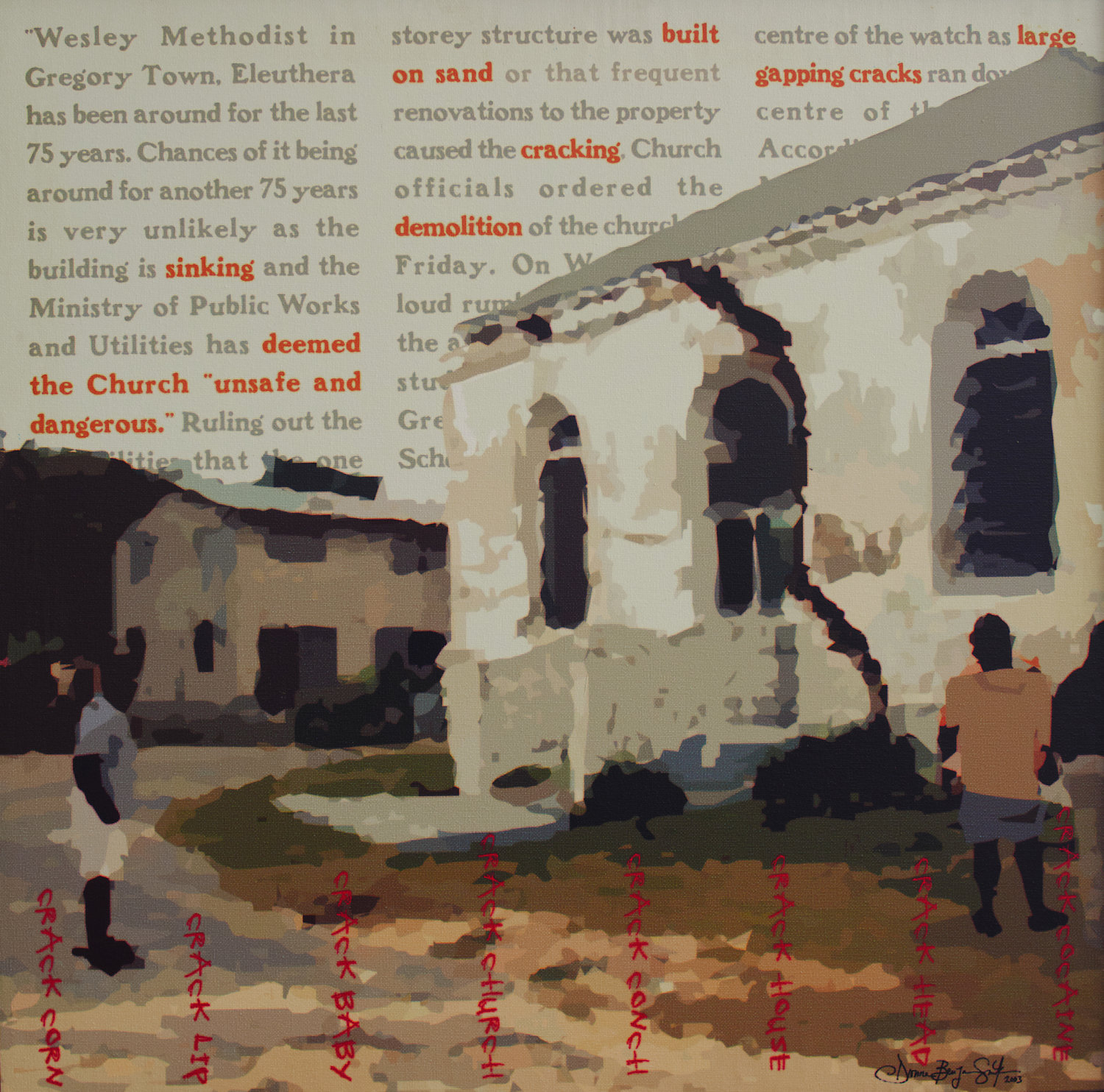

From the Collection: “Built on Sand” (2003) by Dionne Benjamin-Smith

By Natalie Willis.“Built on Sand,” (2003) by Dionne Benjamin-Smith, is in some ways the sister work to “Bishops, bishops everywhere and not a drop to drink,” (2003). Both works are of the same dimensions, which instantly makes us as viewers try to compare them and view them in the same plane when they are placed near each other, but, it is the critique and use of religion as their subject that makes them read like chapters in a book, feeding into each other and helping to inform a greater whole.

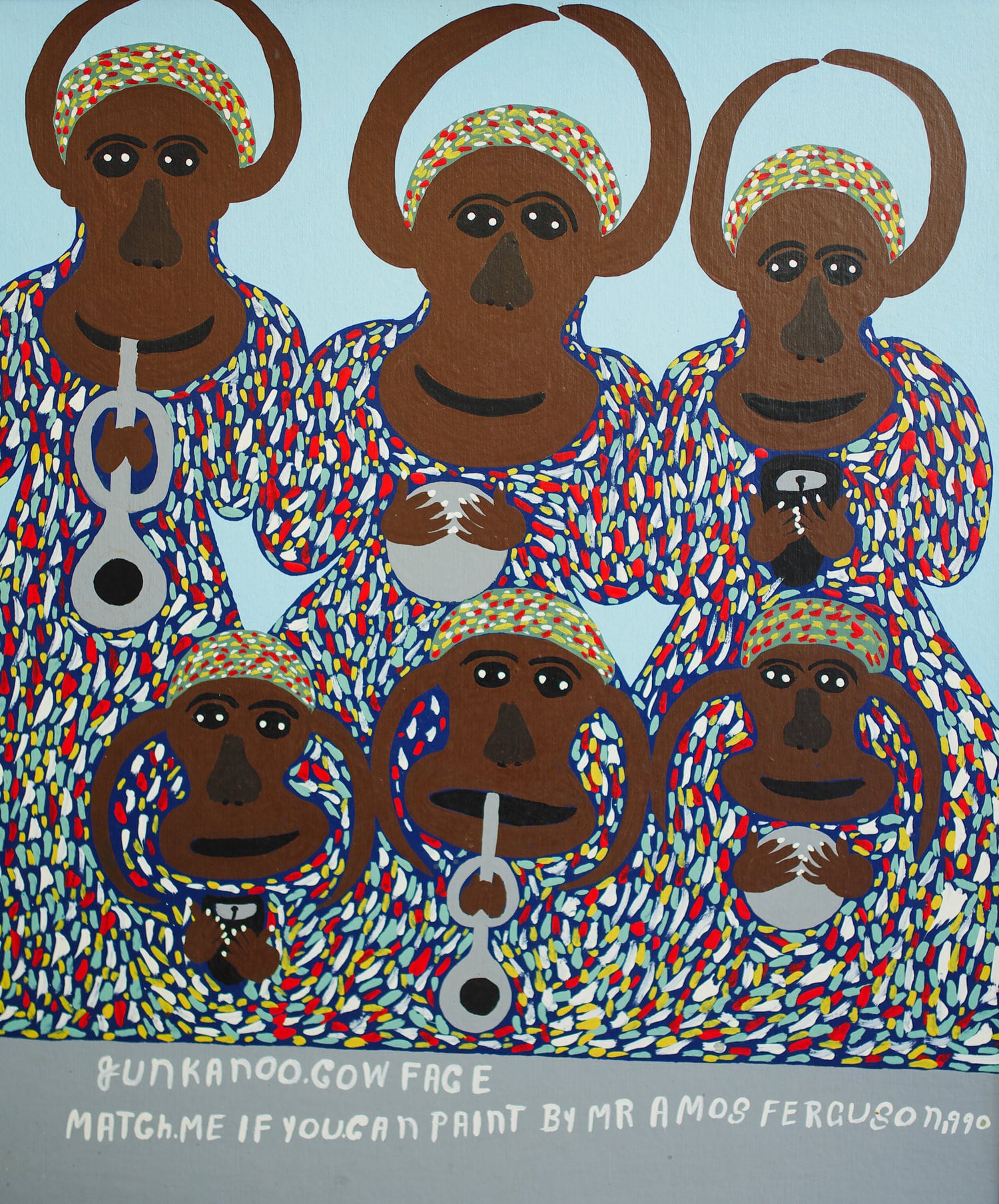

From The Collection: Amos Ferguson’s “Junkanoo Cow Face”

By Natascha Vazquez.

Bahamian artist and icon, Amos Ferguson radiantly portrays the spirit of Junkanoo through an energetic array of repeated imagery and texture in Junkanoo Cow Face – Match Me If You Can, an iconic piece in the Gallery’s National Collection. His interest in flattening the picture plane and depicting a graphic quality to the work is evident in this work, nodding to the style that he became widely known for. Ferguson used colour and repetition of form for impact and clarity. Arrangements of patterns flood his paintings, a visual language closely related to that of Bahamian culture, and in particular Junkanoo.

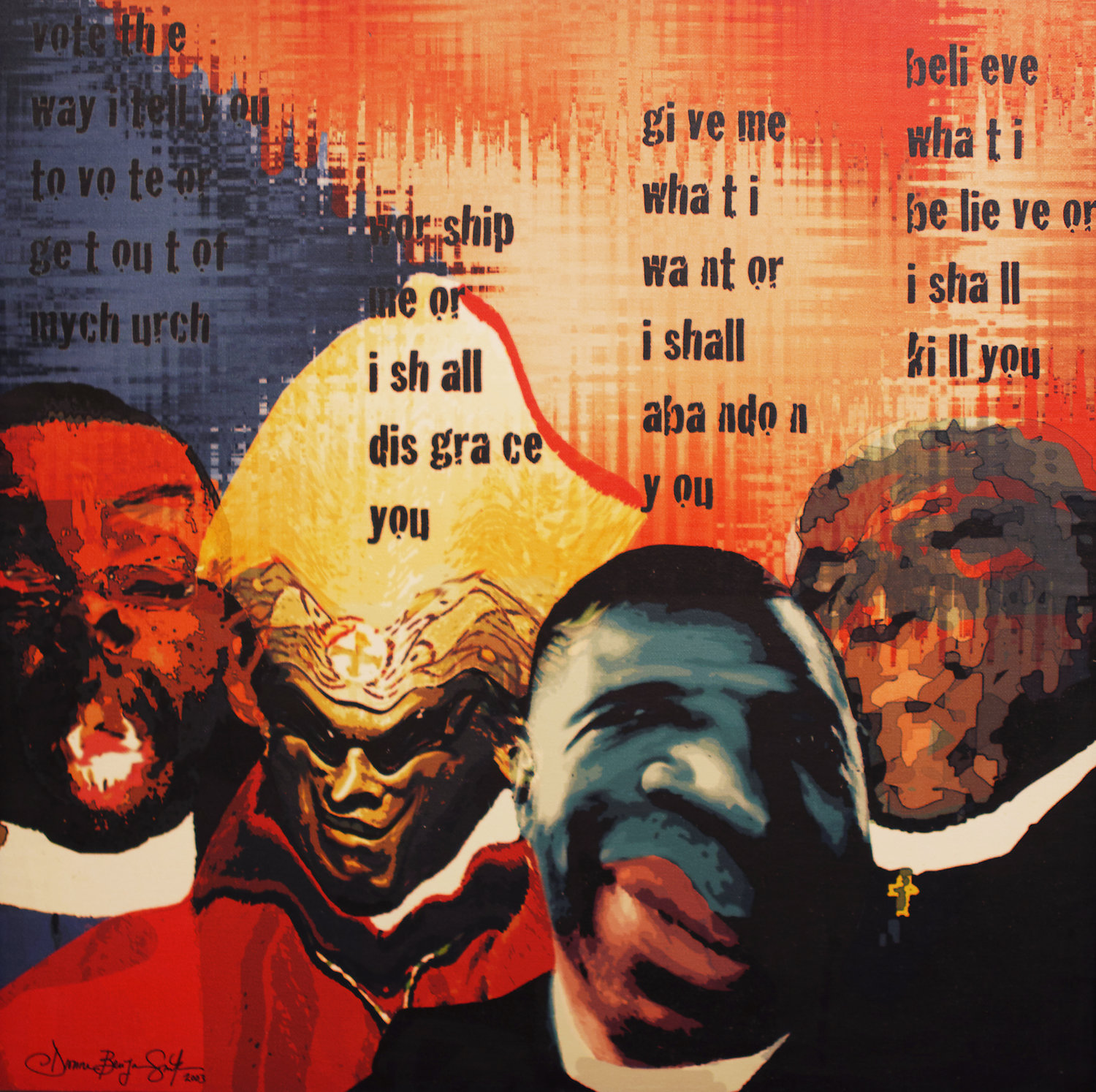

From the Collection: ‘Bishops, bishops everywhere and not a drop to drink’ (2003) by Dionne Benjamin-Smith

By Natalie Willis.Works dealing with the divine, with Christianity, with the spiritual, are very much rooted in what we consider to be part of our representation of Bahamianness. In looking to the work of Dionne Benjamin-Smith, an artist and graphic designer known for her pithy and no-holds-barred practice – and very informative and inclusive newsletter designed and created by herself and her partner – we can see a proudly proclaimed Bahamian woman who identifies with her Christianity taking acute aim at problems with the way we view religion in our country.

From the Collection: Lynn Parotti’s “The Blastocyst’s Ball: A Journey Through the Drug Induced stages of IVF”

By Natascha Vazques. Lynn Parotti is a Bahamian artist exploring themes of natural and biological landscape, those surrounding us and within us. In “The Blastocyst’s Ball,” Parotti displays a triptych of non-objective form and colour, alluding to something that may exist within biology or perhaps, more specifically, in our bodies. Each piece shows a unique arrangement but commonly shared hues and rigid texture created through repetition generate a strong sense of unity between them.

From the Collection: Michael Edwards’ “Untitled II”

By Natascha Vazquez. The interpretation of abstract art entails an inventiveness that allows you to discover for yourself the meaning behind the work. It’s an organic process, it has no equation or set of rules – the art presents itself and you are left with little information to process it. For many, this is unsettling. As humans, we yearn for understanding – we desire clear, detailed instruction. Abstract art provides none of that. Revolutionary colour field painter Mark Rothko says, “Art that truly engages us is felt even when you have turned your back on it.” There’s something really special about that – about feeling the sensation of a work beyond its physicality. It’s when you can feel the strength of the painting from across the room. You can stand in the space the artist once occupied and imagine him or her in that same spot, debating over the next smear of black or red pour or blue dot. Similarly, Jerry Saltz says, “Abstraction disenchants, re-enchants, detoxifies, destabilises, resists closure, slows perception, and increases our grasp of the world.”

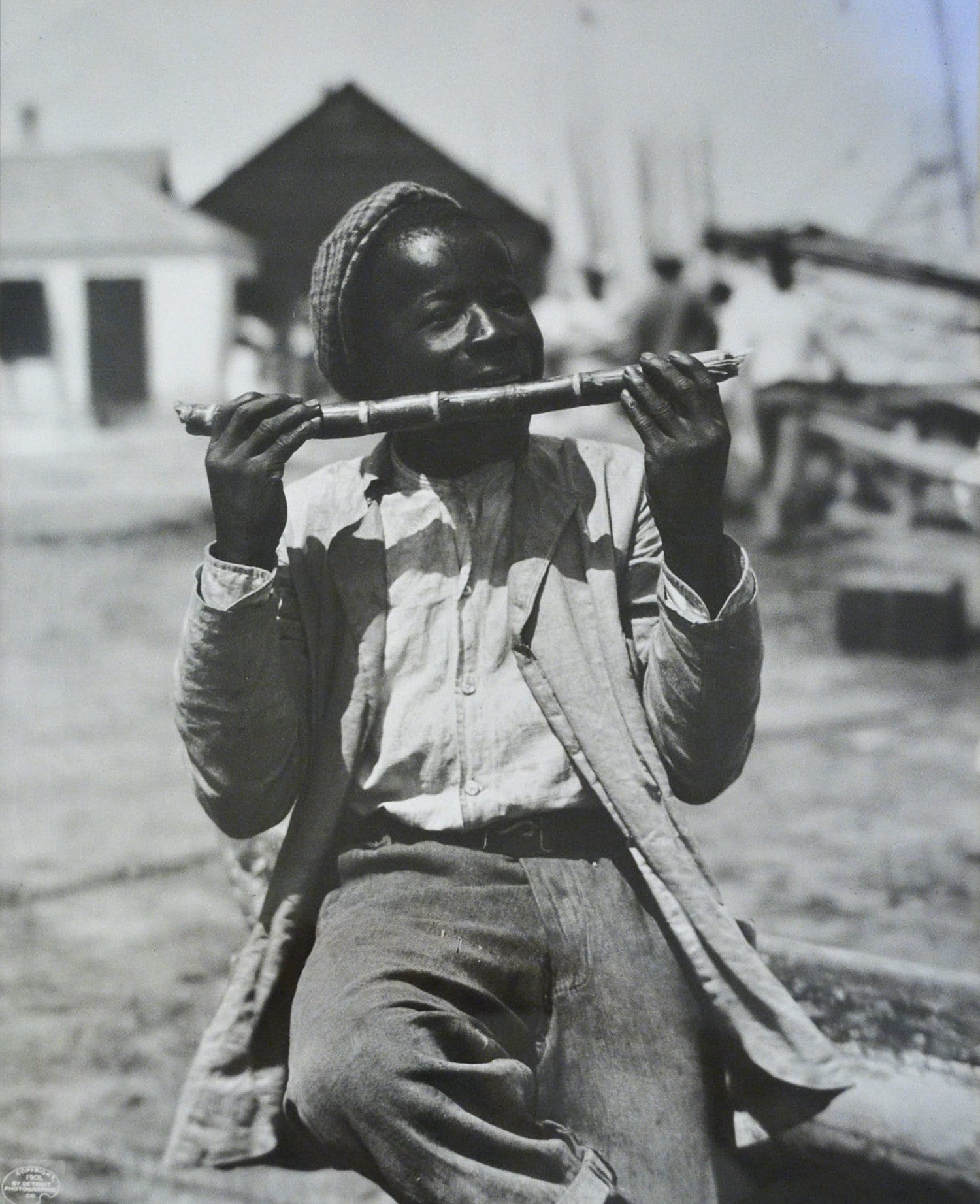

From The Collection: “A Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901) by William Henry Jackson

By Natalie Willis. “A Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901) by William Henry Jackson is part of the suite of historic colonial photographs in the National Collection. Jackson was an American, who started a photo studio here after emigrating from New York in the 1870s and is one of the small group of colonial migrants whose pictures help us piece together part of the story of the time. According to the catalogue for “Bahamian Visions: Photographs 1870 – 1920,” curated by Krista Thompson, Jackson first came to The Bahamas at the request of the Governor of the time, Sir William Robinson, in 1877. Since around 1856, Jackson worked as a landscape painter, colourist of photographs and also owned a studio specialising in Daguerreotype photographs. In addition, he manufactured albumenized paper, managed a stereoscopic printing shop and had even worked as a Civil War photographer. Many of these things seem very far removed from us now, but they were staples of photography at the time.

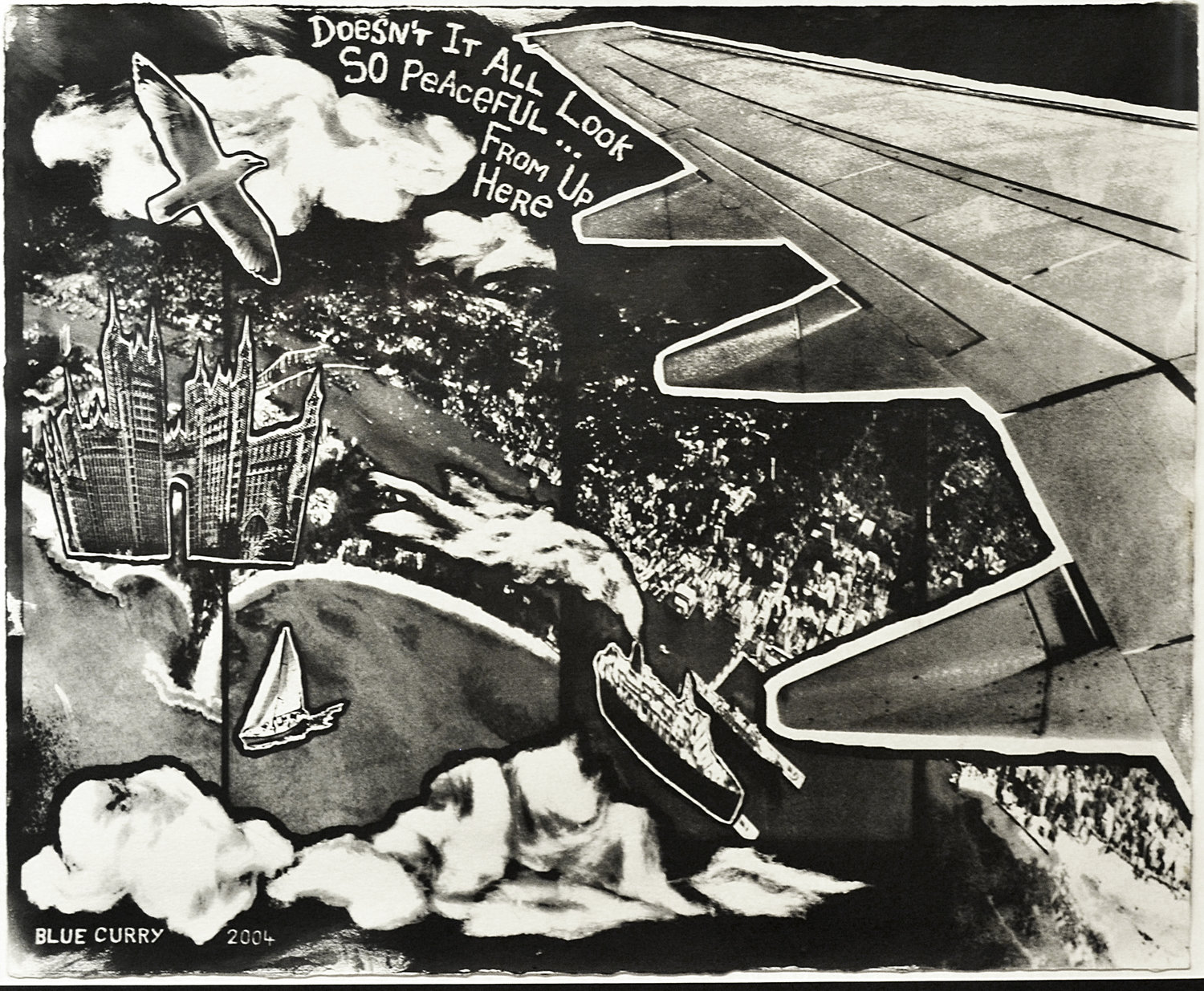

From the Collection: Blue Curry’s Nassau From Above

A sense of gloom surrounds Nassau from Above through Blue Curry’s use of black-and-white collage-styled imagery, paired with the words “Doesn’t it all look so peaceful… from up here.” We are slapped with sarcasm as these words overlay an image of Nassau seen from above through an airplane window.

From the Collection: Lavar Munroe’s “The Migrant”

Lavar Munroe’s “The Migrant” is an illustrative portrayal of a spindle-legged, knock-kneed nomad carrying his home on his back. In many ways, the tale this digital print tells of the ubiquitous image of the immigrant is reminiscent of the Phil Stubbs classic song, ‘Cry of the Potcake.” The xenophobia and self-hate we deal with as a nation is quite easily summated in the lyrics of the catchy tune, “they don’t love me, they only know me when they need me,” and Munroe’s look at the struggle of the emigrant bolsters this when we think of our history as forced immigrants. For instance, can we image our Bahamas without teachers, nurses and doctors from elsewhere in the region working alongside those we consider to be ‘born’ Bahamians?