By Natalie Willis

Reclining nudes, women posed ‘just so,’ we’re all quite accustomed to this kind of figuration and portraiture in the art world. Even those of us who are just dipping our toes into the wonders of the art world associate art with this kind of imagery. Art students at universities the world over can be found squinting in deepest concentration, poring over their depictions of a nude model before them – often a woman – and trying to figure out form, perspective, how to capture the ‘essence’ of this stranger they’ve met. It’s part of the canon, in many ways.

The anonymous, somewhat notorious, feminist art collective known as the Guerrilla Girls point out something rather pressing that we take for granted when we look at these images that are so deeply rooted in the public psyche as what art and art history is about: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but over 85% of the nudes are female.” It’s a comment that incites cringes and looks of surprise, but the surprise quickly fades – the art world is, after all, still part of the world we currently exist in, warts and all.

Installation shot of “Untitled (Paula Rego)”, 2017 by Gabrielle Banks. “The Mark of a Woman” is Banks’ solo show of work on view at the NAGB. Image courtesy of the NAGB.

This obsession with the female form, but apparent lack of support of women artists, shows us that while the imbalance here is gaining slightly more attention and care these days, it is still indicative of the difficulties of having an art world that is as wrapped up in imbalances of influence as our daily lives are: patriarchal privileges and the disadvantages of women, particularly women of colour, are very much real and very much felt, especially in our corner of the world. This is why the work of Gabrielle Banks gives us a refreshing moment to sit back for a moment and consider where women of colour stand in the greater context of global art history and also, importantly, in the representations we see of black women in media.

Her new solo exhibition, “The Mark of a Woman,” currently displayed in the Project Space of the NAGB (National Art Gallery of The Bahamas), takes some of the great art-historically significant works one might come across in closer study of the history of painting and shifts the images ever so slightly, in such a simple but significant change, to make us totally reconsider the place of many of these greats in the Western canon of painting in regards to our own lives. The RISD (Rhode Island School of Design) student takes these famous works and simply changes the subject from white women to black women – and this insertion of the black female figure instantly moves the narrative into some weighty topics to navigate: the male gaze, the white gaze, appropriation. It’s all in there, and boldly – in both size and colour – Banks forces us to reckon with the things we take as default, particularly the Western whiteness we use as a baseline for experience and wrongly so when we think of just how much happened in the world even before history began to be framed through this lens.

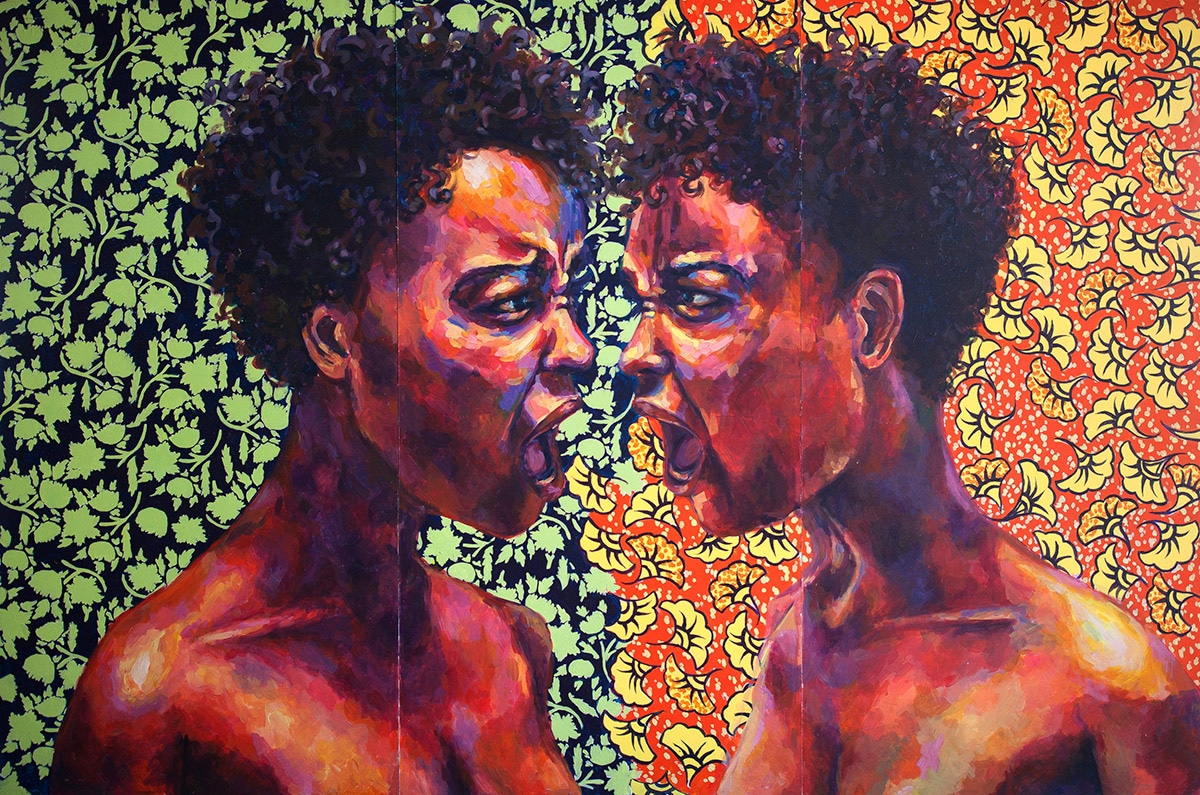

Installation shot of “Untitled (Kehinde Wiley)”, 2017 by Gabrielle Banks. “The Mark of a Woman” is Banks’ solo show of work on view at the NAGB. Image courtesy of the NAGB.

In this region particularly, we are quite used to having others take what is ours and turn it into their own: our music (wherein currently, dancehall beats are now being taken by artists from elsewhere and called ‘tropical house’ music), and even our land itself (we know the colonial history and legacy that we grapple with heavily even now). So then, for such a young artist, and a young biracial woman at that, to take on some of these greats as direct references in her work and shift their focus onto black women is a pretty heavy statement, but one that needs to be made.

Banks began to notice the historical disparity of images going on quite early in her time at university. “I started realising that there was something lacking in the representation around the female form when I started taking art history classes going out to see exhibitions and galleries more often. I was finding that when the female form was represented, it was often in a way I wasn’t very comfortable with. There was always a nude, or a reclining nude, or someone sprawled on a bed or spread on sheets, or women in some form of servitude. And then, looking more closely, I noticed that with women of colour, particularly black women, were almost not represented at all. The few instances I found early on where they were represented, it was in comparison to some other “higher class” female, who was often Caucasian and European, and usually the black woman was there to highlight these other women’s class or status.”

“Untitled (Kehinde Wiley)” 2017, Gabrielle Banks, oil on board, 48 x 72. Image courtesy of Melissa Alcena.

Looking more closely, the fact that Banks is painting in oils – given the rich history of the medium, for instance, when we think of Renaissance painting – is a proclamation within itself. Where Banks saw a historical lack of representation, she literally inserted herself and other women of colour into these works and into this timeline, putting us back into the narrative by giving us this imagined history and playing with the representations we see of ourselves day in and day out. She challenges the notion that black women only be represented in limited terms: as “the help” (both in popular media, and in many an oil painting of old), the hypersexual being, the strong woman, or the black ‘mama’ mystic. It is a limited palette to use to paint such a multiplicity of personal histories and experiences of black womanhood, and this is perhaps why Banks chooses to render herself and those like her in such bright colour, away from these ‘black and white’ tropes.

The thin layers of oil colour build up and sediment into a colourful, saturated, and varied version of history, in a way that almost surreal – and isn’t the idea of seeing black women at the forefront of these historically-influenced images surreal in some way? The cultural amnesia and erasure of black women from history, and people of colour and women in general, is palpable and being challenged – those marginalised are re-writing their stories from the margins into the center, and the old powers we become so accustomed to are now having to be re-thought through.

“Untitled (Paula Rego)” 2017, Gabrielle Banks, oil on canvas, 72 x 60. Image courtesy of Melissa Alcena.

Banks shares: “I’m really keenly interested in art history, and there are some great painters, but there are lot whose subject matter I find really disturbing, there’s just some really problematic imagery. So I take their images, and try to reclaim it in a way that I felt better represented how I felt or better represented women – not necessarily as a way to feeling empowered, but just a more sensitive way to communicate that particular image.”

In looking to other artists of colour – such as the famed photographer Carrie Mae Weems, whose photographs of black women in everyday life show us in such stark honesty, and Kehinde Wiley’s realistic paintings of black people, heroically elevated and proud amidst patterned tapestry-like backgrounds – Banks finds a way to problematize the white, Western canon of art, whilst simultaneously paying homage to other artists of colour in our black diasporic art history who give us the representation we never quite had.

Artist Gabrielle Banks, currently studying at Rhode Island School of Design. Her work is on display at the NAGB in the solo exhibition, “The Mark of a Woman”, in the Project Space. Image courtesy of Melissa Alcena.

The women in Banks’ arsenal of images confront the viewer, looking directly to meet your gaze – as boldly as Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” had done to such scandal in 1863 – or they look away, disinterested, atop a surrealist tropical backdrop of saturated colour that is reminiscent of Paul Gauguin – who also, it is worth noting, had a habit of painting women of colour in Tahiti, among other things we know him to be (in)famous for. Some of the women also seem to reject manicured ideals of femininity as much as they reject the male gaze, as some present themselves with an almost androgynous ambiguity about them, or unflattering angles and rolls of skin proudly on display.

Banks, who tries to not spend more than two weeks at a time on each work, produced all of these pieces in one semester, and her urgency in moving from work to work, and reference to reference, shows not only a love of the medium and practice of painting, but a need to produce these reflections and questions on black womanhood that she wants to be able to see. As the Guerrilla Girls also so succinctly, and so aptly put it: “You’re seeing less than half the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of colour.”

“The Mark of a Woman” will be on view at the NAGB from June 22nd to July 30th.

Nice looking paintings from the Bahamas… ????????????????

Comments are closed.