By Malika N. Pryor-Martin.

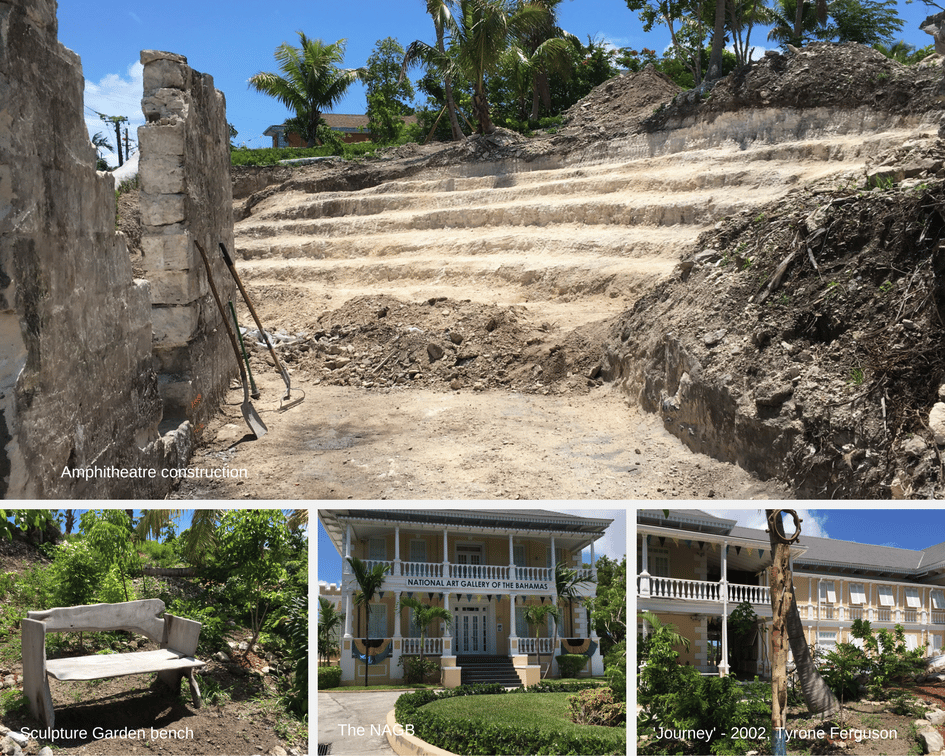

The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas opened on July 7, 2003, just three days before the country would celebrate its 30th year of independence from the British. Nearly a decade in the making, the NAGB was mandated with the task of preserving and propelling Bahamian culture through the visual arts.

As a nation, we wrestle with the vestiges of a difficult past that is both wondrous in its resilience, beauty, non-violent resistance and depth, and then incredibly painful, in its treatment of the predominantly African-descended population, the misuse of its natural resources, the violence and displacement of the poor. It is a story and series of stories that are frequently told on the walls of the NAGB by Bahamian masters, like Max Taylor, Amos Ferguson and Jackson Burnside, as well as the next generations’ practitioners: Dionne Benjamin-Smith, Lillian Blades and Jeffrey Meris, among others.

However, the walls on which the artworks hang, also tell a story. Villa Doyle, the facility wherein the NAGB is housed, was the built in the 1860s by the then colony’s first Chief Justice, Sir William Doyle. It was later expanded in the 1920s to include a ballroom among other features reserved for the elite. Over time, it was sold, abandoned and fell into grave disrepair. Before 1997, when the seven-year restoration began, the grand colonial home atop the hill, was shadow of herself, a ghost. But next door was a lesser known yet equally haunting narrative.

Affiliated with the country’s first African hospital, which was constructed in the 1700s, there is now only one structure that remains and might be part of that history. The cut limestone walls that enclose the mound of earth and fallen masonry and separate the hospital from the Lane that bears its name, was constructed with the resourcefulness and ingenuity of the enslaved and also the free settled Africans who built them. Like its neighbour, in time, the property was abandoned, eventually becoming an overgrown dumping ground for the Villa Doyle, historically and more recently for any dubious person with a stolen good or trash bag they wanted to lose.

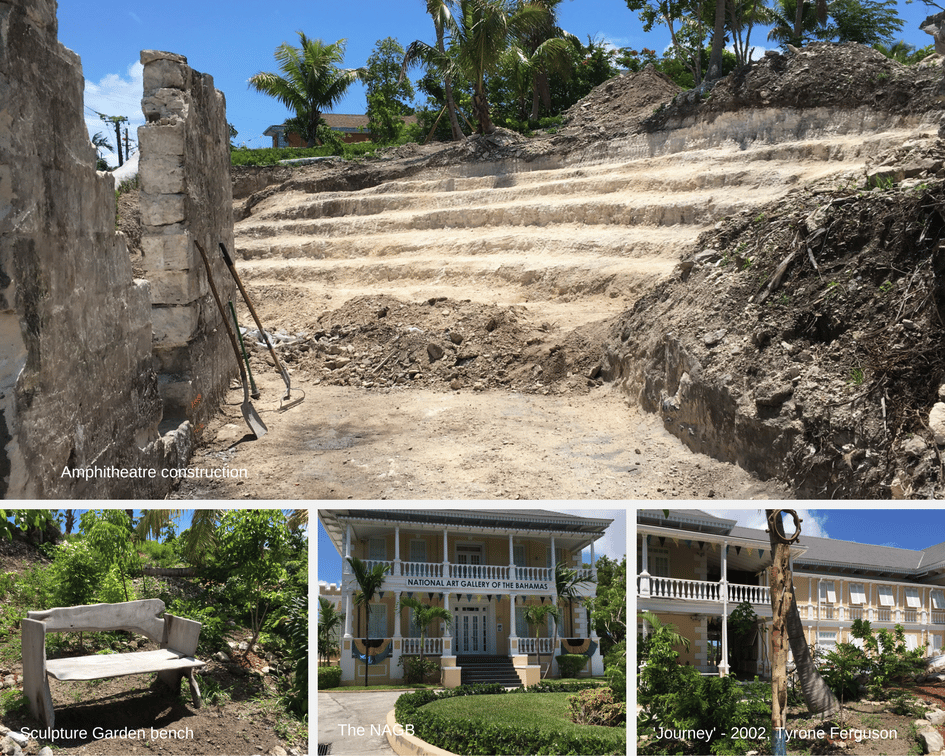

Today, the space is being resuscitated: day by day, week by week. The NAGB Sculpture Garden, which recently installed its first sculptural exhibit, is continuing to take shape thanks to our partners; The Bahamas National Trust, The Leon Levy Preserve, The Bahamas Horticulture Society and the countless volunteers, who have dedicated time to the process of healing a wounded space that once literally healed others. In addition to the Garden, the Gallery has broken ground on its Amphitheatre. Burrows Development, the general contractor and Alexiou & Co, the architectural firm on the project are labouring to complete the project before the year’s end. The newedifice will not only provide a dedicated space for films and talks, it will serve as a true point of intersection for the fine and performing arts. Yet another facility—overseen by Anthony Jervis Architects, Ltd.—is also in the planning stages, to extend our ability for education and conservation.

The trappings of colour, class, national origin, orientation, and status: old ideas and modern tropes act more as cages, trapping us, however metaphorically, in our respective predilections, pushing us further away from each other. But art has the power to bring us together. So, we are working tirelessly to break down those barriers by offering a holistic experience that is as evocative as it is inviting. Bahamian visual arts, like the country it represents, is the culmination of countless narratives that the walls – the people, our communities, tell. At The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, we are listening.