Antonius, AfriCOBRA, and the Aesthetics of a True-True Bahamian

Letitia Pratt●

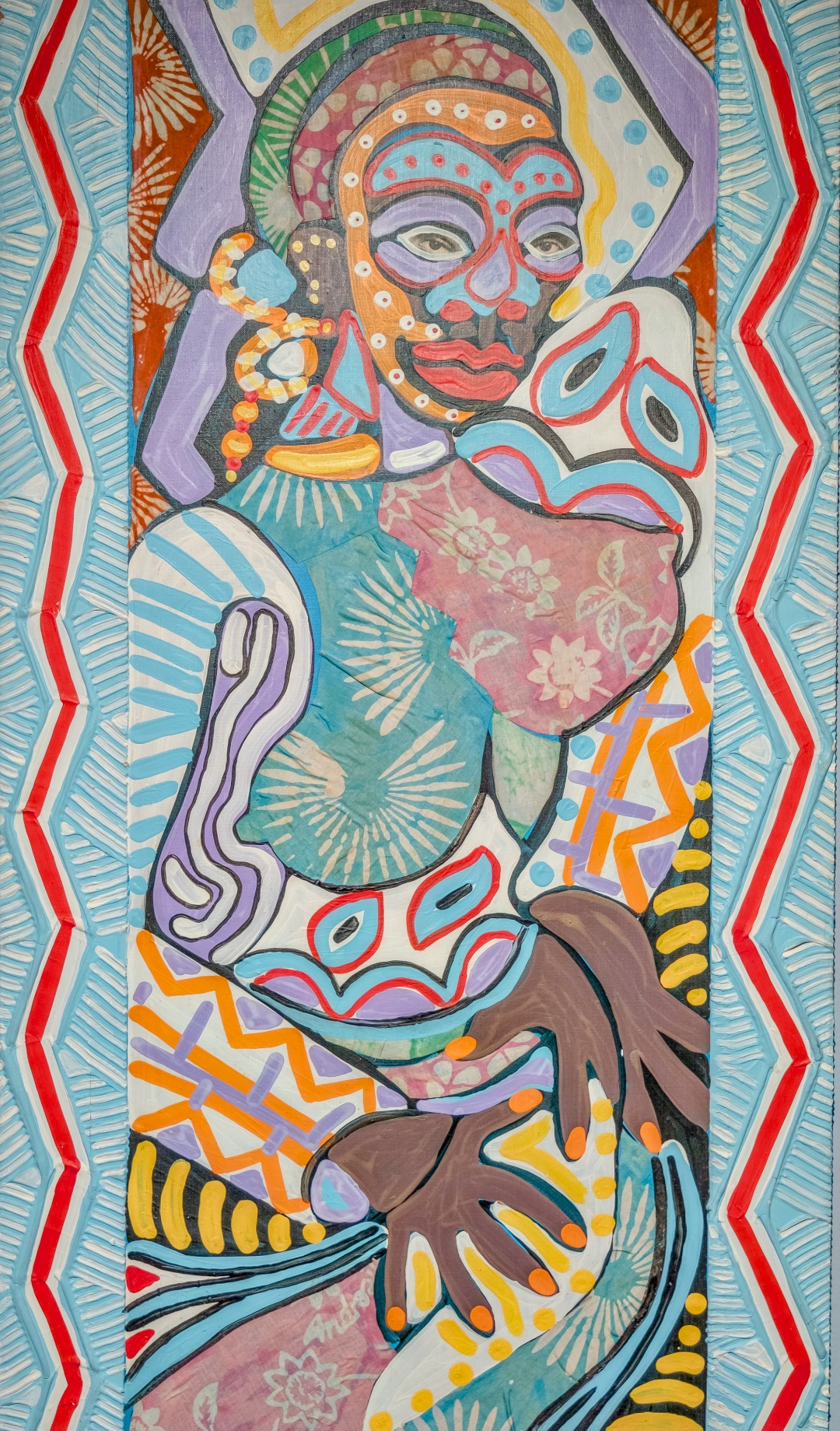

When we take a look at Antonius Roberts’ 1996 collage-painting Once Upon A Time (1996), we recognize the essential markers of Bahamian modern abstraction: it is filled with vibrant colours, an amalgamation of portraiture, and it is charged with an overwhelming amount of movement. Even the name is rooted in Bahamian identity: storytelling is one of the key components to Bahamian artmaking—even across disciplines—and the name Once Upon a Time both evokes this history and signals that the piece itself tells a story of its own. The mythmaking in Roberts’ abstraction was not only inspired by his own Bahamian-ness, I argue, but was a successful attempt to connect his practice to other Afro-diasporic creative practice of that time. In the mid 1990s, Roberts looked to the art collective AfriCOBRA as an anchor for this experimentation, and we often see this in the aesthetic language that he used in his paintings of that decade.

The collective AfriCOBRA (the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) was formed in 1969 in Chicago, Illinois, and was instrumental in disrupting narratives about what it means to be a part of the African diaspora. Born out of the American Civil Rights and Black Power Movements of the 1960s, their philosophical mission was to form an aesthetic language that connects all Black peoples, and responds to the long history of racist and colonial representation in fine art. The five founding artists—Barbara Jones-Hogu, Jeff Donaldson, Gerald Williams, Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, and Nelson Stevens—reclaimed these narratives through creating pieces that countered the Eurocentric imagery that flooded the mainstream. What they were doing, in essence, was attempting to define Afro-diasporic art, as a counternarrative to the traditional institutional standard of artmaking that has been taught for centuries.

Roberts, along with many Bahamian Artists post-independence, had about the same motivation: they sought to also create a visual language that is not only identifiable as “Bahamian”, but that connects with the aesthetics of the Afro diaspora. The 90s were only two decades into Bahamian independence, and within the political milieu of a newly minted Bahamian landscape was a constant re-negotiation of what it means to be truly “Bahamian”, and what this new-found “Bahamian-ness” looks like. Patricia Glinton-Meicholas states that “Bahamian artists have been among the leaders in negotiating the redefinition of Bahamian ethos and identity,” and argues that the late 60-70s was the beginning of both political freedom in, and the freedom to define, Bahamian art. “One might say that the politics of the era—the advent of majority rule and independence”, she writes, “produced substantial seeds for the generation of [Bahamian art and identity].” As such, the first two decades of the independent Bahamas was concerned with developing an aesthetic that reflects what the people believed to be true about their own experience living on the islands. This aesthetic was usually defined with bright colour, broad strokes that created a lot of movement, and portraiture or landscapes that reflect iconic Bahamian cultural people or scenes.

The commitment to reflecting Afro-diasporic life through aesthetic practice is where the Bahamian post-independence art philosophy and the philosophy of AfriCOBRA overlap. Jeff Donaldson states that this philosophy is grounded in the decolonisation movements of the 1960s. He goes on to state:

Beginning in the 1960s, this tendency toward multicultural synthesis has grown exponentially among numerous individuals and groups of artists across the African continent, in several European countries and throughout the African diaspora of the West. Moreover, in the West, unrelated groups of artists — AfriCOBRA2 in the United States and, in the Caribbean, Groupe Fwomaje of Martinique, Kou- kara of neighboring Guadeloupe, and B’CAUSE in The Bahamas—have issued manifestos that espouse region-related visions of the formal qualities of the trans-African style/movement.

This desire was not only found in the Bahamian politics of identity—it permeated the Afro-diasporic zeitgeist in ways that reverberated through the modern art world. In Bahamian art history, philosophical groups like B-CAUSE (Bahamian Creative Artists United for Serious Expression) and Jammin were instrumental in solidifying a new understanding of what Bahamian art can look like. Erica James refers to this time as an “explosion of perception of Bahamian Art” and argues that “each post-war generation has in individual ways managed to merge the forces of Bahamian culture with the pulse and imagery of global movements in art.” In essence, these groups were good at forming the aesthetic that came to represent Bahamian life.

With artists like Antonius, the inspiration becomes even more evident in the work that they produced in the 90s. AfriCOBRA’s philosophies are very apparent in works like Once Upon A Time, most notably, the concept of “a commitment to humanism”—i.e. the work has to be inspired by the African people and their experience. The portraiture within the piece exemplifies this well; Roberts succeeds in reflecting a specific type of Bahamian reality that connects to African-ness through Junkanoo imagery. The name Once Upon A Time also references this rule, outlining that the painting is in fact the story of the Bahamian people: full of energy, connected to the ancestors, and building, as exemplified through the image of the Manhattan bridge in the upper right corner of the composition, towards a new modern vision of progress. The work itself is a reference to its own purpose: to build a story of Bahamian realities, and Roberts is good at creating this narrative through these aesthetics.

Like most of the work done by the members of AfriCOBRA, Once Upon a Time is resoundingly hopeful. The painting communicates its optimism primarily through its use of colour. The bright, busy palette does two things for this painting. Firstly, it connects again to the aesthetic principles of AfriCOBRA, in which color and “free symmetry” are key to the composition, i.e., there is always a syncopated, rhythmic edge to a piece created by the group. Secondly, the bright colour palette again affirms the “Bahamian-ness” of the work and aims to prop up the narrative of optimism that Roberts creates. The story then becomes about the resilience and pride that the Bahamian people possess.

The work of Roberts, like many Bahamian artists, is constantly defining what it means to be Bahamian. This is not incongruent with the state of living on these islands – as we approach our 50th year of independence, we are still in a constant re-negotiation of our identity. In the first decades after independence, it was crucial to look outward to Black power movements and art collectives like AfriCOBRA to draw connections to the Afro-diaspora. However, the new generation of Bahamian artists is starting to look internally for inspiration: responding to our own construction of Bahamian identity and responding to artists like Antonius Roberts himself.

- Donaldson, Jeff R. “AfriCOBRA and TransAtlantic Connections.” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Duke University Press. Durham: 2012.

- Glinton-Meicholas, Patricia. “Art of The Bahamas: An era of negotiating self-definition.” Published on the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas Website. Retrieved April, 2023.

- James-Hogu, Barbera. “Inaugurating AfriCOBRA: History, Philosophy, and Aesthetics” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Duke University Press. Durham: 2012.

- James, Erica. “Bahamian Modernism” The National Art Gallery of the Bahamas. Nassau: 2007.

Letitia Pratt is Associate Curator at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. In addition to her curatorial work, she is a writer and poet with an MFA in Writing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Pratt has held positions as a writer and curator at the D’Aguilar Art Foundation and SITE Galleries at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her creative writing has been featured in the NAGB’s NE8 and NE9, and published in esteemed literary journals, including WomanSpeak, Bookmarked: PREE New Caribbean Writing, and The Caribbean Writer.