By Natalie Willis. The issue of rape, and subsequently its deafening silence, is a shocking social disservice in this country, and it is something we should be using our voices to ask many, many questions about. With a failed gender equality referendum, and marital rape still being legal, it is hardly surprising that the statistics for sexual assault in The Bahamas continue to rise. Read between the lines of the statistics and there’s still not enough room for the 60%+ unreported sexual assaults, let alone the “pick-up” lines (see: street harassment) that feeds into gender-based violence. The statistics for the rape of men are even less likely to show the severity of the situation. The sexual violence against women, children, and men, in addition to the commonplace armed robbery and assault, we are left with a labyrinth of heartache and bloodshed that is difficult to find our way out of.

Currently browsing: Stories

Under Attack: Averia Wright’s Elevating the Blue Light Special and the Dualities of Bahamian Identity

By Ethan Knowles. War for much of the Caribbean is a remote idea – a thing of books, films and faraway lands. In a region characterized by calm waters, light breezes and laidback locals, the notion seems oddly out of place. But the idea is not just a distant one. It’s also awfully dangerous. War necessarily conflicts with what Caribbean nations like The Bahamas ‘should’ be, that is, a peaceful escape for the worn and overworked. Put simply: conflict in the Caribbean is off-brand. And in our Bahamaland, where at least sixty percent of the GDP and half the workforce rely on a carefully manufactured and embellished brand image, being off-brand can be about as deadly as armed conflict. As the daughter of a straw vendor in a family of straw vendors, Bahamian sculptor and expanded practice artist Averia Wright is well-acquainted with the brand of paradise we manufacture here. Her work, which grapples with issues affecting both The Bahamas and the region at large, is particularly concerned with tourism and its role as a neocolonialist system in the country today. Elevating the Blue Light Special (2018), Wright’s submission for the “NE9: The Fruit and The Seed,” addresses just this concern, exposing and critiquing the commercialisation of identity which is so central to the contemporary tourist economy.

A Garden: Letitia Pratt Creates New Folklore in Response to Biblical Patriarchal Storytelling

By Kevanté A.C. Cash, NAGB Correspondent. Amid the cacophany of fragile male egos, speaking ever so loudly over the voices of the most vulnerable, the question arises: where can the disenfranchised go to feel safe and protected? To feel comfortable in one’s own skin? To be loved for themselves entirely, and not be used, abused, mistreated or abandoned? Organised religion, for years, has done a superb job in keeping the marginalised on the outskirts of the conversations that seeks to give them liberty. The marginalised meaning ‘the backbone of society’, the movers, makers, shakers and doers, the ones who are made to feel ashamed for how they express themselves and their sexualities. These people–women–I argue are the most disenfranchised group of individuals within society.

“Water: The giver and the taker of life”: Edrin Symonette’s “Salt of the Earth”

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, The University of The Bahamas. Salt: pressed into flesh, brines and cures, drying left on lines, as flies land and enjoy a feast of decaying flesh; a colonial resource extracted from the spaces of the once far-flung regions of empire. Salt is a way of life; a natural resource abundantly available in the islands; the pain of enslaved Africans who laboured tirelessly in its corrosive briny suspension as they raked salt under hot sun. Their skin ulcered, backs bent and minds steeled against the dehumanisation of exploitation and enslavement.

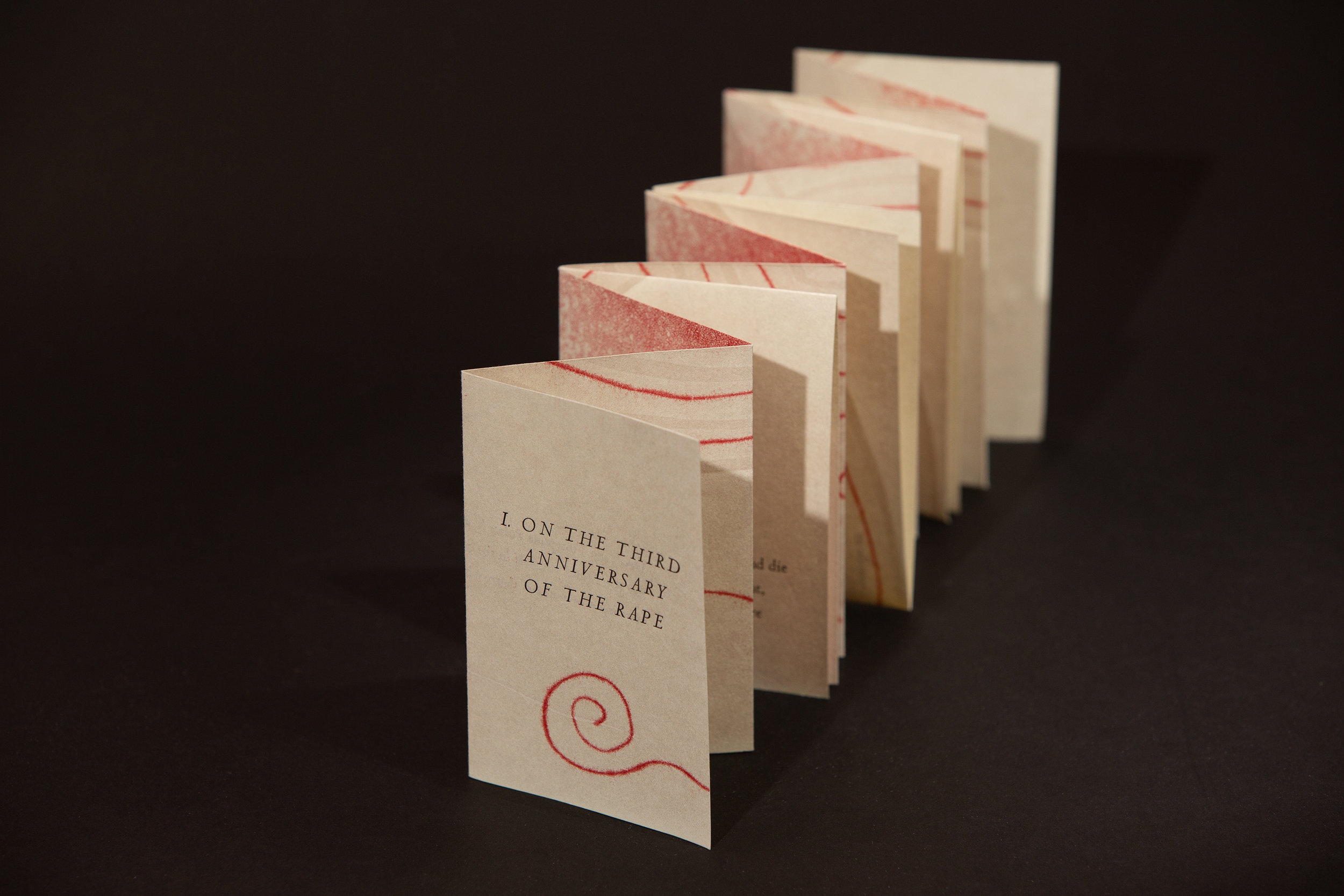

Painting to heal: Artist Gabrielle Banks lays bare the burdens of her troubled past

By Kevanté A. C. Cash, NAGB Correspondent. The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) continues to provide a platform and be a safe space for artists across all genres to lay bare the sentiments of the heart through thematic responses to exhibition calls that seek to engage the wider Bahamian populace. Gabrielle Banks, student artist at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), took the opportunity of submitting works into the ninth National Exhibition (NE9) “The Fruit and The Seed” as a way to vocalise her thoughts and opinions and to heal from past pains and traumas. Furthermore, the artist also intended to inspire a discourse that is oftentimes swept underneath the rug and left for the minority of society to engage in.

Strange Fruit: Kendra Frorup’s Poignant Banana Plumes

By Natalie Willis

Though artist and educator Kendra Frorup may be using the imagery of the banana flower in her work in “NE9: The Fruit and the Seed”, this is anything but a literal interpretation of this year’s theme. Frorup cleverly takes the image of the banana plant – whose fruit is rife with symbolism in the Caribbean and the world over – but takes on its less represented anatomy, the flower, and gives this to the audience for consideration. The plant that has become iconic in the region with slavery and plantations, as well as the more base and salacious hypersexualised iconography emerging from the difficult tropes the slavery era brought forth that we are still forced to contend with today.

Vulnerable ecologies: This Woman’s Work

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, The University of The Bahamas. Feminist ecology and ecocriticism have usually pushed for embracing the environment and awareness of the same in our life ways. The intersection of art, ecology and a female’s perspective is often fertile space for serious discussions and new understandings of society, and its socioeconomic and sociopolitical challenges. The environment and ecology are under serious threat as we can see from Naomi Klein’s This changes everything: Capitalism vs the Climate (2014) along with the U.S. government’s recent report on the dangers of climate change as well as the United Nations’ Report on Climate change. Capitalism, usually seen as the driver of economies and the joy of consumption, encourage a particular disregard for conservation and natural balance in favour of expansive and unlimited profits. Meanwhile, artists, nature lovers and regular citizens face the threat of extinction through rising sea levels and increased storm frequency and ferocity due in large part to human consumption of fossil fuels and living outside of harmony. One of the links that we as island dwellers refuse to make is the link between the patriarchy and masculinist discourse that deny the existence of climate change and sea level rise. They reflect a deeply colonial mindset that negates the outward reality. They also offer the limitless life of market growth and profit. However, all things are limited, there is no unending elasticity to profits.

The Weight We Bear: Heino Schmid’s monumental drawings in the NE9

By Natalie Willis. This year’s National Exhibition (NE), “NE9: The Fruit and The Seed”, took time to cultivate, to bear fruit, and much care was taken in tending to the roots of art in The Bahamas. The NE serves as a thermometer or litmus test, a finger on the pulse of what is happening in our creative culture here. Of the 38 artists showing work, one particular “fruit” was very, very big indeed.

Heino Schmid’s contribution to the 9th National Exhibition “NE9: The Fruit and the Seed” is, in short, meta. Allow me to explain. His three monumental drawings (measuring in at 9 feet tall by 5 feet wide), housed in heavy, monumental frames, are a gestural portrayal of one human being carrying another on their back. These drawings were then assembled in their heavy frames on the ground floor level of the NAGB, with the heavy glass to protect them slotted in, and then these heavy drawings in their heavy frames were strapped and hoisted to have the 300lb+ weight lifted by the strong backs of several of the NAGB “ninjas”, (along with some very dear friends). In this way, the work is meta, though perhaps self-referential or self-reflexive better serves the description. It’s a sort of divine irony, that works depicting the act of labour of carrying another human being are enacted in the process of displaying the work itself.

MasC Off: NE9 Artists Challenge Social Binary Views on Gender

By Kevanté A. C. Cash, NAGB Correspondent. During conversations of sex and sexuality do we rarely address the elements of gender, gender identity and gender expression. However, what is gender? How is it different from sex? How is it expressed, and who gets to claim it? Over the last decade or more, millennial culture has started dialogues and much-needed debates over the complexities, toxicities and nuances of masculinity and femininity. Breaking down the stereotypes of such, debunking the myths and redefining it for themselves through the power of the “interweb”, social media, art and artistry. When singer, songwriter and recording artist Rashad Leamount-Davis joined forces with photographer Allan Jones for their project ‘MasC Off’ with the Ninth National Exhibition (NE9), their mission was simple: to address these complexities, toxicities and nuances that exist within the realm of masculinity, specifically for Black Bahamian men, some of whom may or may not identify as LGBTQ+ members of society.

Dave Smith “Violence, the beauty of paradise”: The art of capturing the lingering impact

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, The University of The Bahamas. In the Caribbean, like most of the world with globalisation’s flattening of the world, as Thomas Friedman’s The World is Flat (2005), demonstrates, inequality increases as the local place is transformed by the international space. Art and the art scene belie the international and interstitial connectivity of local and global. Dave Smith’s Caribbean Sunrise (2018), is emblematic of this using juxtaposition and colour in striking yet contradictory and discordant ways. We never think of the Caribbean as a violent space, yet with this history of occupation and exploitation is is quintessentially violent, it’s geography hides violence: the violence of the encounter or the discovery, that in itself marks a violent erasure of what was once there, though overlaying it with a imagery and imaginary of paradise, almost like Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). The allure is dangerous.