The Nation/The Imaginary

Dates

19 October 2023–October 2024

Location

NAGB

All galleries

Excerpt from curator’s essay by Letitia Pratt:

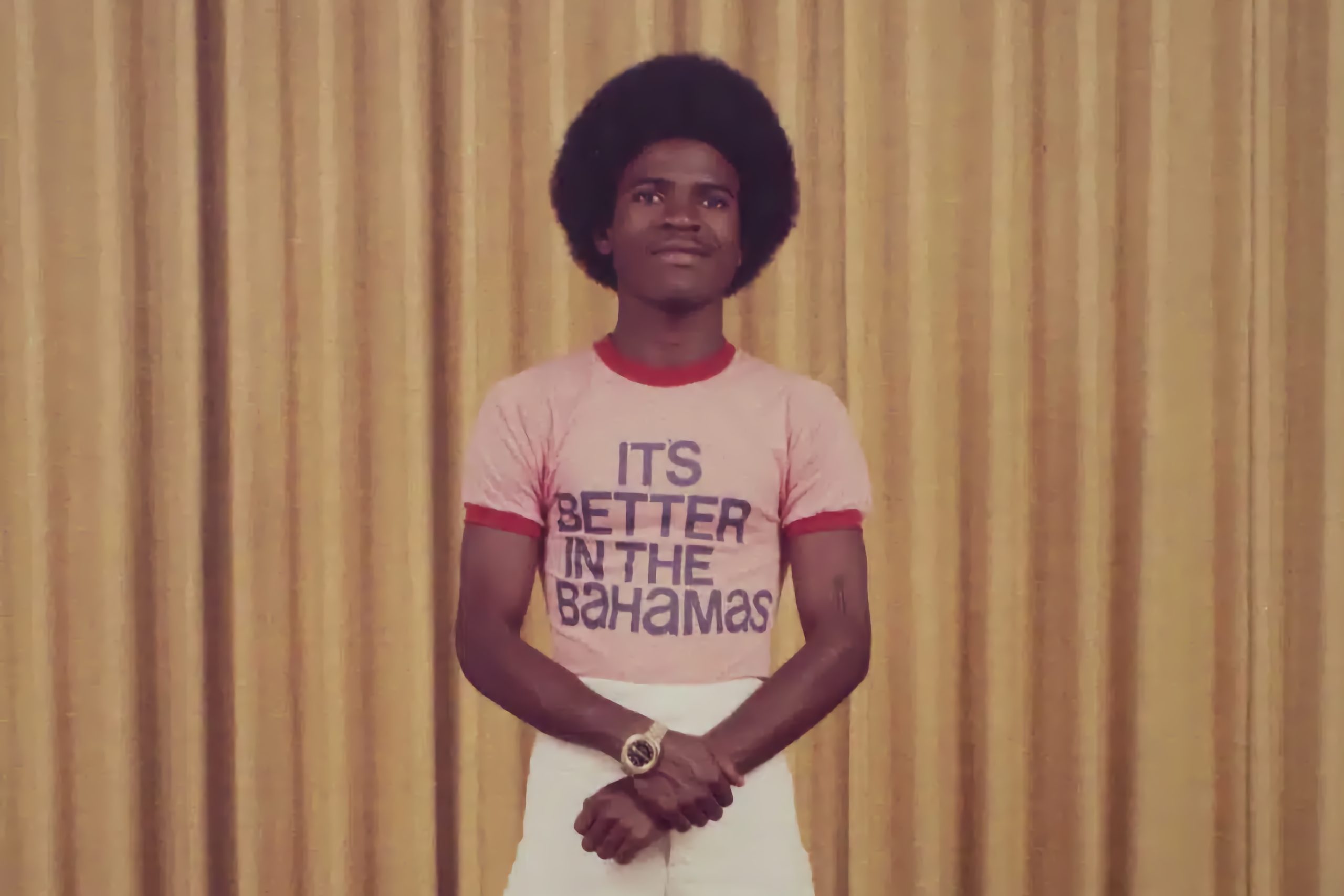

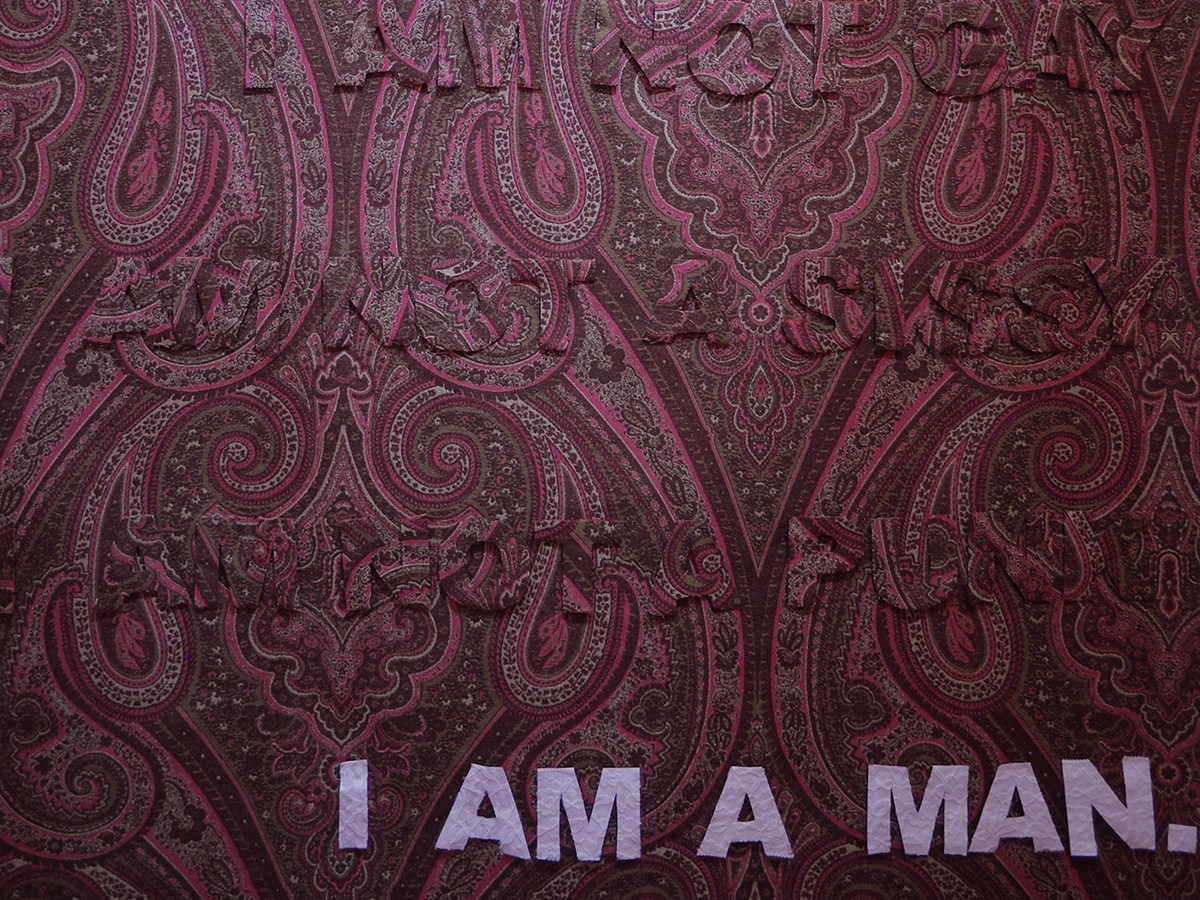

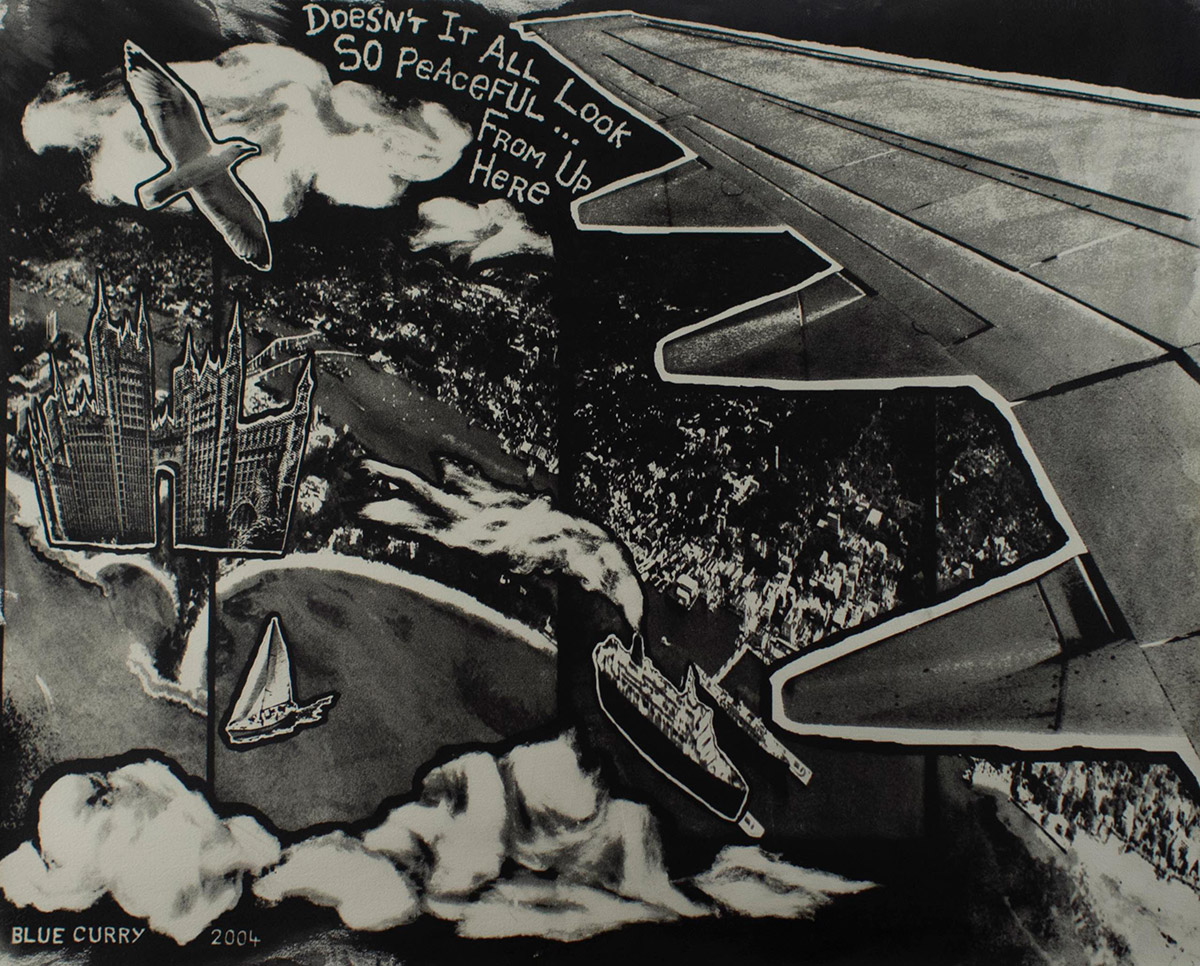

Picture this: a mounted frame of a sun-dappled beach, the coolness of an undisturbed shoreline, a photograph of a market woman, hands akimbo, with a warm, welcoming smile – these images have pervaded our cultural imagination, especially before independence, through centuries of crafting paradise along British imperialist lines. The National Collection, established in July 2003 to support the Inaugural National Exhibition by Dr Erica James, is filled with imageries of nationhood, whether that be in line with the colonial frame or concerned with deconstructing the paradisical myth that haunts our daily lives. The work acquired by the museum reflects how we identify as a Bahamian people, and how we respond to different matrices of oppression.

In the essay “Art of The Bahamas: An Era of Negotiating Self-Definition”, poet Patricia Glinton-Meicholas states that Bahamian artists have been among the leaders in negotiating the redefinition of Bahamian ethos and identity. She argues the museum’s importance in nurturing this process: “Well positioned, the museum coaxes Bahamians into discovering and valuing a truer history, heritage, and culture of our country. It also encourages appreciation of the real genius of our people […].”To this end, the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas has been a hub for intellectual and artistic ingenuity, fostering a space where Bahamian artists are free to imagine who we are beyond ideas imposed by tourism and false paradise.

The Nation/The Imaginary, explores juxtapositions of myth/reality, paradise/plantation, and the importance of the imagination in transcending colonial ideation. As artists bear witness to our political coming-of-age, they craft stories that challenge power and help guide us towards self-knowledge. With over 500 pieces, the collection is only a snapshot of this story/making – which is a great place to start imagining.

The Nation/The Imaginary is curated by Richardo Barrett, Curatorial Manager, and Letitia Pratt, Associate Curator.

Upcoming events

See what’s on and upcoming at the NAGB.