Reconnecting to the Divine Feminine: Tessa Whitehead Challenges the Perception of Bahamian Painting

Blake Fox · 13

Calling upon fear, surrender, and angst, Tessa Whitehead presents us with an incredibly personal impression of her dreams, memories, and experiences in a transcendent series of figurative paintings in her first solo exhibition in The Bahamas titled “…there are always two deaths.”

With the advancement of photography and digital art, it has become increasingly uncommon to see human figures in modern figurative painting as photos ostensibly create a more accurate representation of a person—the visual likeness at least. There is however something to be said about the power of photographic allusions in Whitehead’s work. She references archival family photographs in this series, which when translated to painting deepens the mood, presence, and even the history of the work. Belgian painter Luc Tuymans remarked: “We are living in a society that is predominated by an enormous amount of visuals, but they’re not really looked at. What painting does is slow that mechanism, which is necessary, so you can also say something about it.” Upon entering the gallery, the linear placement of the paintings provides a clear line of sight for viewers and the large-scale format allows for a more intimate experience with the works.

For me, the surface quality of the painting And Us (2018) is the most distinct and captivating in the collection. Filling a large section of the canvas is the lower half of a figure wearing a dress. The undulating folds of the dress create a fluidity as the figure appears to glide across the painting—almost in a supernatural way. It is enchanting. The tenebrous colors used by Whitehead manages to convey a sinister undertone in an image as unassuming as a dress. The texture of the dress is created by using a soft brush to smoothen out the wet oil paint—similar to the technique used by acclaimed German painter Gerhard Richter—creating a buttery and supple surface, obfuscating the image of the dress and expanding the possibility that this might not be a dress.

The texture further expresses a certain degree of murkiness: Is it actually a dress? Could it possibly be the trunk of a mystical tree? It’s not that I’m solely seeking recognizable images in the work, but the mind often subconsciously makes these associations in abstract and figurative works. These images can be helpful to the viewer, establishing a frame of reference that allows you to create your own narrative.

There is no doubt that there is a certain mysticism to Whitehead’s work, and nature and womanhood are salient fixtures throughout the entire show.

Moreover, womanhood and the matrilineal nature of Caribbean societies are suggested in the repetition of brown and grey brushstrokes that emulate a congregation in tow, as the main figure approaches a phantom or spirit—perhaps for guidance. As Jamaican author, Errol Miller noted, in Jamaica, matriarchal forms of kinship that exist among the lower class originate from West Africa and the aftermath of plantation slavery. Having Jamaican roots, Whitehead honors matriarchy and its importance in her development.

Historically, the women in her family would have worked arduously and collectively in the cultivation and betterment of the family. It is commonplace that Caribbean women develop a kinship as a means of survival during social and economic unrest. Relevant to the discussion of matriarchy is the indigenous Guna people of Panama and Colombia. Comprised of approximately 50,000 people living on 49 different islands across the Guna Yala archipelago, the Guna people remarkably possess complete autonomy and still live the way their ancestors did—with the bare necessities that many would deem uninhabitable after access to modern amenities. Akin to the Guna people’s special bond to the earth is Whitehead’s portrayal of women being deeply—almost spiritually—connected to the natural world, enveloped in the lush foliage. Superficially, the Guna Yala archipelago seems undeveloped, but their autonomy, their acceptance of gender fluidity, and the matrilocal nature of the community put them ahead of many seemingly advanced world powers.

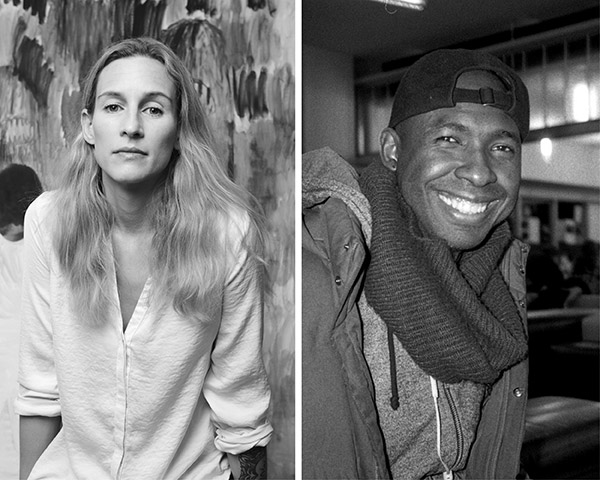

Whitehead’s work is a critique of the typical lens through which Bahamian and Caribbean art are so often viewed: often male-centred, often featuring the ubiquitous colonial seascape with luminous turquoise waters and vivid greens of coconut trees. Yet, her sombre palette of greens, browns, greys, and blues still elicit a relationship to the natural environment. She is challenging the notion of what Bahamian art and painting is and is deliberate with her choice of unpretentious colours that truly speak to our environment. Tessa Whitehead’s work makes for an interesting dynamic when contrasted with Chan Pratt’s Resurrection show and I anticipate that it will spark a critical conversation around the definition of Bahamian art.

…there are always two deaths is curated by Holly Bynoe, chief curator at the NAGB. The show is open alongside Chan Pratt: Resurrection and will be on view through 28 July 2019.

Blake Fox is an artist, art educator, and cultural worker from Nassau, The Bahamas. He has worked in the visual arts for over 5 years, where he’s held a creative practice and facilitated educational programs. His photography has been featured in international publications and he has exhibited at the Pro Gallery, Popopstudios ICVA, the Project Space at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, the Island House, and TERN Gallery. He is interested in art and museum education as agents for social change.