Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, University of The Bahamas

Island life is beauty-filled and provides intense moments of feeling through natural splendor from the greens of the foliage, the oranges, fuschias and purples of bougainvillea vines, the fabulous colours of the water. As humans, we need to live in beauty or somehow a part of us dies. The loving and nurturing part of us withers, like leaves in a fire, and vanishes. We need to be around beauty and we need to feel beautiful. When these needs are not met we are often left in tatters or become empty shadows.Chan Pratt’s work in the retrospective show, eleven years after his passing, “Resurrection” shows the beauty of colour and the positive feelings it creates. It serves as an apt reminder of how important connecting to beauty is.

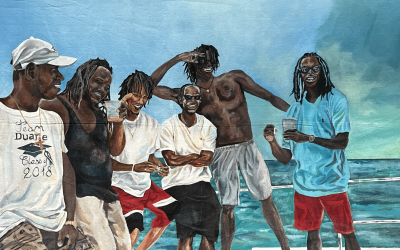

untitled, 2019. Tessa Whitehead. Oil on canvas, 54’ x 84”. Work courtesy of the artist and image courtesy fo Roland Rose.

The presence of art and music in communities where suffering is too prevalent provides amazing tools and conduits for the healing of past traumas and present-day violence. Within this community space, art allows for authentic speaking and generates feelings of self-worth. When denied this connection to beauty and empathy to human subjects they shrivel up and turn inward. In Pratt’s work, we see this beauty all around our island paradise, yet it is cut off and removed from so many people. His vivid use of colour enlivens the landscape and humanity brings dignity to the area. When people are denied this dignity they then become violently disempowered and disenfranchised.

Bread and Puppet Theatre–a name derived from a theatre’s practice of sharing fresh bread for free, with the audience of each performance to create community, and from its central principle art should be as basic as bread to life–shows how these trends can be reversed with community-based theatre and community-based art, which are like bread, essential for human life.These are not exclusive, off in private sectors or away from the mass of people. When we see the separation as insurmountable we fall victim to the splitting of humanity.

In Tesa Whitehead’s powerful exhibition that opened this past Thursday, at the NAGB, the show quotes one of my favourite writers, Jean Rhys, who writes in Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) “There are always two deaths, the real one and the one people know about” the real one is the death of the person. The two protagonists of the novel, Antoinette and her mother Anette inhabit post-slavery colonial Jamaica and Dominica and the action moves between these spaces. They live with Pierre and Christophine and the novel is one of the most stunning and poignant 19th-century English novels and complex character developments that I have read to date. Rhys recontextualizes Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), where there is a famed madwoman who lives in the attic. The Caribbean as imagined into being by Bronte produces madness and is a terrible place as it leads otherwise men into lascivious relations. This is of course barring the sexual violence and exploitation of slavery and imperial and colonial project. Scholars Susan Gubar and Sandra Gilbert later use this as a study of feminism in their groundbreaking text, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (1979). The tragedy of Rhys’s novel is the devastation of the community through patriarchal power and colonisation.

It is the struggle for recognition and power after slavery when power asymmetries change and yet don’t, and Blacks are angry and take it out on a community of women. However, displaced anger is never righted. The female subject is further subjugated in what becomes a story of nature, the loss of belonging and the absolute need for an identity. Antoinette’s husband, the aristocrat Rochester, decides to change her name, and this is arguably her first death as her identity is stripped from her. She refers to it as Obeah, and turns to Christophene for comfort and help, but colonial law and patriarchal power intervene and Antoinette and Christophine are lost as the patriarch takes possession of all her family wealth through his ownership of her.

Carolling: On the way in, on the way out, 2018. Tessa Whitehead. Oil on canvas, 50’ x 62”. Work courtesy of the artist and image courtesy of Roland Rose.

Whitehead’s work really grapples with this beauty and death as it explores the vanishing presence. These experiences of disconnection, dissociation and dislocation, violence are long-lasting legacies. Art and beauty are amazingly effective tools for working through some of these issues. For example, provide a space to have a community garden—as they have effected at NAGB—and relations begin to change. The act of bringing beauty and a real connection to the land into existence is a soul building experience and the ability to break down non-physical but perceived barriers to sharing in art, music and theatre is an act of liberation.

Rhys’s novel much like the work done in these two exhibitions at the NAGB speaks to the need to belong in the natural beauty of the known and the essence of breaking bread together, to use a very religious, across denomination and faiths figure of speech that evokes human connecting and welcome. This kind of allowance for beauty to flow through people’s souls into their daily lives is the kind of action needed in traumatic and conflict-torn communities. We see community-based art programmes doing wonders in post-conflict spaces and working to reduce the post-traumatic ill effects of dissociation.I love the ways in which “..there are always two deaths” and “Resurrection” speak to each other in very unintended yet human and heavenly tones. Beauty is essential for the soul. The amount of beauty with the community outreach and summer activities gives access to joy.