All posts tagged: Climate

Everybody and Dey Grammy

Whether we were watching and waiting for the storm to hit directly, or watching and waiting for it to pass from the safety of our own sofas, Christina Wong’s “Everybody and Dey Grammy #hurricanedorian” (2019) struck a cord (and plucked on heartstrings) for all of us. From the hashtag to the sentiment of everybody collectively waiting with bated breath, we felt Hurricane Dorian as a nation — not in a nationalist sense, but rather as people living in, from and tied to this landscape, “born Bahamian” or otherwise.

So Close Yet So Far

As life on islands finds a new normal, we see the importance of connectivity and awareness. Much has been revealed by Dorian’s passage, from the lack of bill payment by some agencies for private companies’ services to aid storm victims, to the need for closer links between people with communities. The beauty of art is that it can capture so many emotions and open up valuable conversations about how and where we live. Naomi Klein in her work The Battle for Paradise (2019), illustrates the gap between words used to rebuild in Puerto Rico in the wake of Maria and Irma and the reality of dispossession and displacement.

Traditional Knowledge Living in the Tropics: Respecting Lifeways

As Dorian’s wake remains with us, do we have time to consider the indigenous, traditional knowledge of the Abacos? Abaco, similar to Inagua and Crooked Island in the south, and even Bimini in the North, has dealt with its share of natural disasters and man-made shocks. Its people are deeply connected to their lifeways and arts.

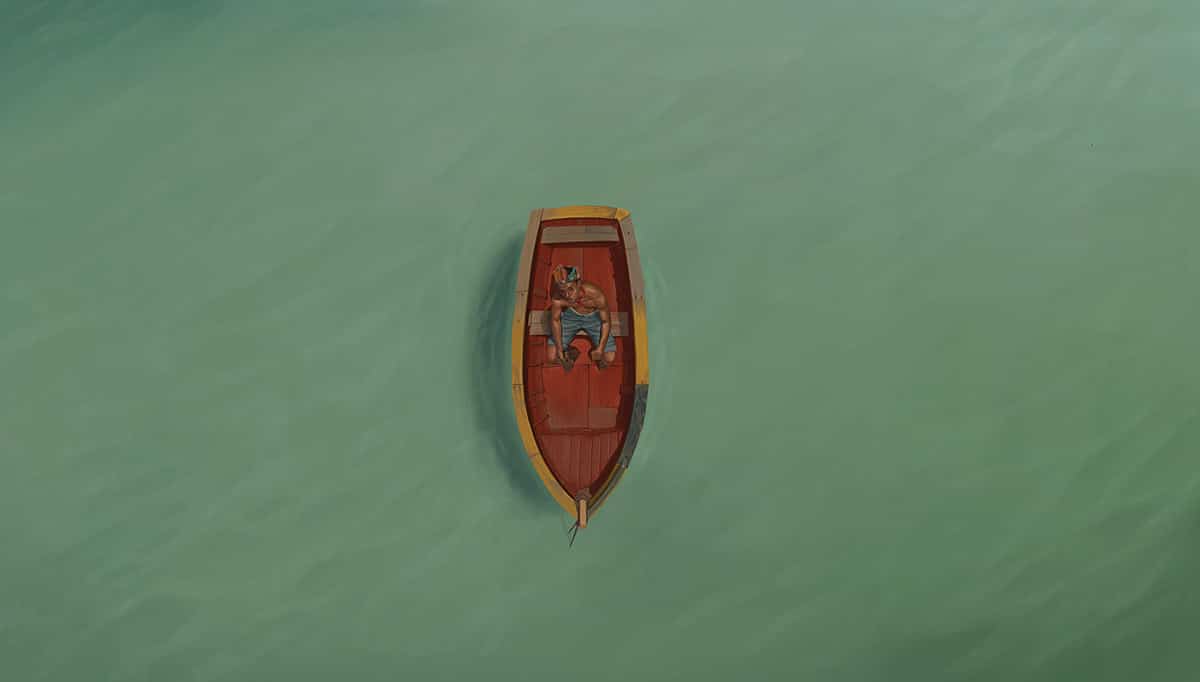

We Live at the Undersides

Resilience in the era of climate crisis and finding the fraternity in loss after Hurricane Dorian. Two years ago, I wrote an article on the impact of Hurricane Irma on the loss of cultural material and the devastation of the landscape, lamenting the single death we sustained here, how we “lost two cultures that day”. I spoke about how many of us, in light of the nature of our dotted, disparate geography, felt the smallest sigh of relief that the more inhabited islands of New Providence and Grand Bahama were not hit, though it did little to soothe the loss of life and property in the Southern Bahamas. This year, I write about another Category 5 storm. This year I write about such heart-piercing loss of life that it’s hard to contemplate how much material loss there is. This year, I write about what happened to one of those “more inhabited” islands, the island I have called home for most of my life, and how the culture and people I grew up with Grand Bahama are underwater, and Abaco all but washed away.

Climate Refugees: On Becoming Climate Refugees or Building Back Differently

We find now that the art of living in the tropics has continued and needs to be a sustained topic of a dynamically changing conversation: how do we retain life in the tropics, become refugees to climate change and flee the islands we inhabit?

Epistemic and Cultural Violence: Powercutting as Light

Anibal Quijano (31 May, 2019) and Toni Morrison (5 August, 2019) – two great thinkers have gone. Nicolette Bethel’s 1990 play, Powercut, produced and performed at the Dundas Centre for the Performing Arts, shows what happens in the dark. Nowadays, lights drop into darkness at least once a day for hours at a time. The violence of structures invisible to the naked colonised eye is only ever gossiped about. We are afraid to cease being what we are not, we do not know how to be who we are. It is the culture of violence and silence revealed through ‘discussions’ around tourism and prostitution, two interlocked economies of pleasure. The Victorian Bahamas avoids discussing these things in the same breath, yet the exoticisation and tropicalisation of space and place speaks to a reality of total erasure of self for what we are not, to pick up on Quijano’s statement. In “The Visual Life Of Social Affliction,” the upcoming Small Axe Project exhibition which opens at the NAGB on Thursday, August 22nd, we see what we are taught/made not to see; we see the violence of not seeing who we are and the trauma of being held in bondage through invisible structures. Powercut reveals a lot of the invisible structures, as do the works of recently departed thinkers Anibal Quijano and Toni Morrison.

The Role of the Arts in Addressing Climate Change

By Blake Fox. Currently on display through June 2, 2019, at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB), the Permanent Exhibition “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean” focuses on how both verbal and visual language have shaped us as a country. One could argue that The Bahamas is a phonocentric culture, meaning speech is given precedence over written or visual work. Because of this emphasis on speech rather than written or visual work, it is no doubt that The Bahamas has a very rich oral culture. While Bahamians rely heavily on oral communication to pass down culture and traditions, visual and written works are just as crucial in communicating cultural beliefs and values in societies. This exhibition highlights Bahamian artwork that serves as a conduit to bridge the gap between our visual and oral culture in The Bahamas.

The Art of Living in the Tropics, Part Three: Silence

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, The University of The Bahamas. Culture is the art of living in a place that speaks of experiences, adaptation and resilience. Culture is the unique expression of spatial and temporal identity or vice versa where a people perform life based on their history and geography. As people are increasingly marginalised through the expansion of capitalist desire into the tropics, the art of living there shifts from a national or an indigenous-peoples-based art to art of magazines and design. How do these things meet so that peoples and their cultures can thrive alongside gated out-sourced post-nationalist communities?

Double Dutch “Hot Water” Opens!: Climate change, Ragged Island and vulnerable ecologies explored.

By Holly Bynoe. The “Double Dutch” series supports the concept of bringing together local and regional artists, irrespective of where they are currently residing, to work with a group of ideas personal, political and otherwise crucial to the development of a contemporary Bahamian identity. These artists and collectives are often divided linguistically and geographically but are united by common historical, economic or practice-based conditions. For this reason, the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) pilot project attempts to create and maintain ties throughout the Caribbean and its more extensive diaspora.