By Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett.

We often ask what makes art Bahamian? Is it about living in The Bahamas? Is it about the colour of the sea, the sky, the play of light? Is it the way we capture images of people in their daily lives that is unlike anywhere else, but also similar to other places? Can Bahamian art be transcultural and also Bahamian?

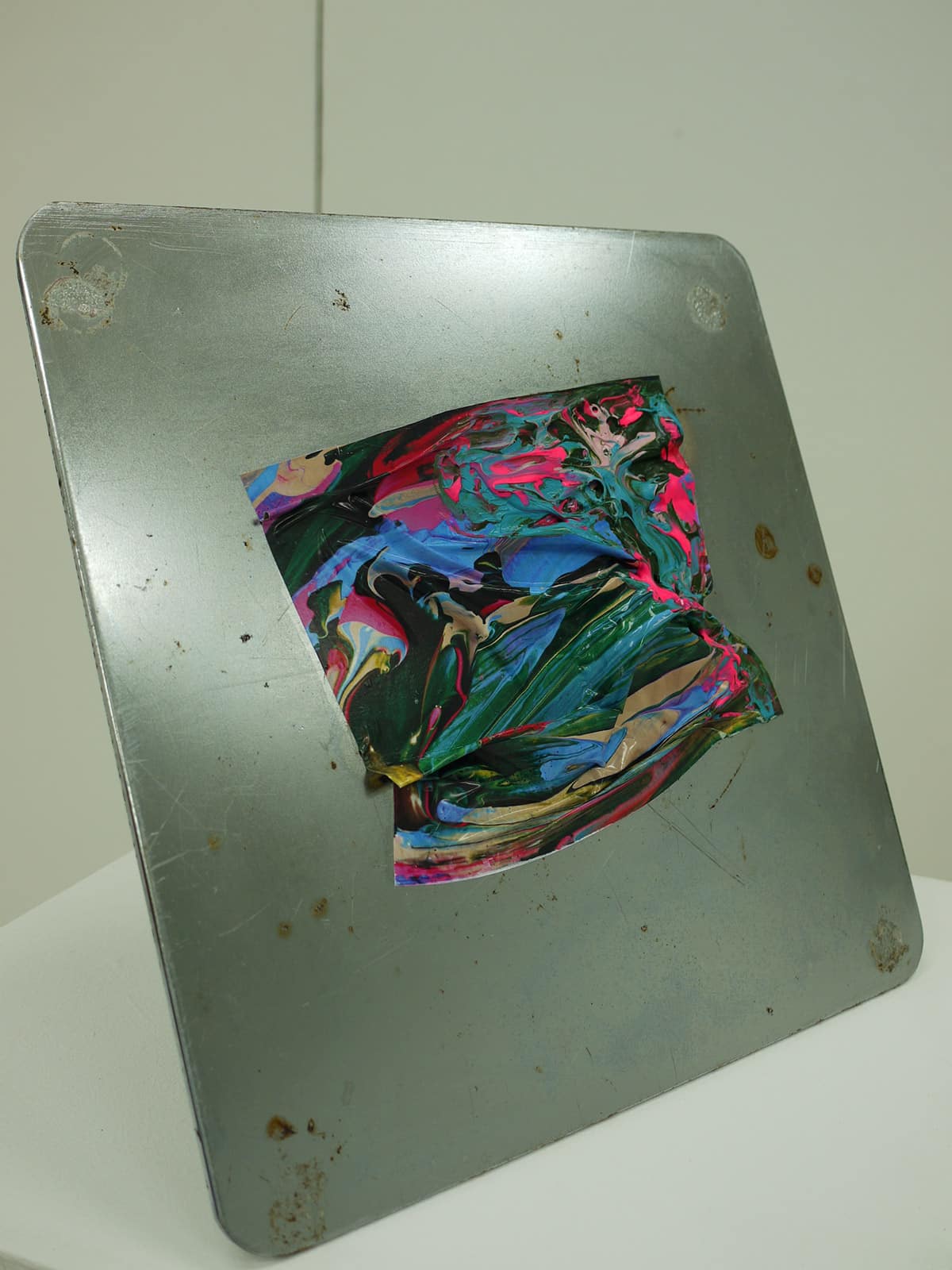

Nowé Harris-Smith. Skin Graft, Photograph. 2016

The world is more transcultural today as people move from country to country, with cable television and various forms of media is blasted into most homes. We have become a place where so much is taken for granted when we discuss culture, but we never really tackle what it means when we say that art is Bahamian. In speaking of “art” we include all creative expressions, not just painting or drawing. We look to woodwork, etching, ceramics, straw work, for example. It is also important to point out that art changes with time; it is never static.

So, as Bahamians change and as generations are exposed to different things and influences, the way they express their creativity will change. How paint is applied to canvas, board, wall, skin will be adapted as new artists take up different challenges. Bahamian art, therefore, is constantly changing. The art of Brent Malone is Bahamian, but it does not limit the scope of what is considered Bahamian art. His work is widely varied and captures so many aspects of different layers of Bahamian cultural life.

Much like Brent Malone, Eddie Minnis is versatile. Minnis uses a knife to create different textures in his work, but he is not limited to that technique. His work has also evolved over the decades. It cannot be said to be the same or to capture one subject. The Minnis family are Bahamian artists, but they are not confined to a narrow frame of bright colours. Kishan Munroe, John Cox, John Beadle, Chantal Bethel, Lillian Blades, Edrin Symonette are all Bahamian artists yet each has a distinct style, eye, and voice.

Each has something to say that cannot be un-Bahamian. When art is produced in the Bahamas by non-Bahamians, does that make it un-Bahamian? We cannot exile art from where it is made or inspired. When driftwood is picked up off a beach in Eleuthera and carved into a frame that surrounds a painting or a box that holds mementos, a crate is used to build a sculpture, a tree is cut to provide for a wooden pen, or to become a part of a handmade, Bimini boat, these are Bahamian. When that same tree is sent to Florida, does that make it less Bahamian? When the Spaniards captured and represented images of The Bahamas, did those form part of Bahamian art? Do these images inform the way we look at ourselves?

Nowé Harris-Smith. Skin Graft, Sculpture. 2016

If we walk through the exhibition ‘From Columbus to Junkanoo,’ currently on view at the NAGB, we can see the differences over an expanse of time. When a boat is built in Abaco and another is built on Bimini, a canvas bag made on Man-o-War or a Straw basket on Acklins or Exuma, that is still different from a Red Bays basket, the stitch, the style are all different, and they are all uniquely Bahamian, made in The Bahamas of Bahamian material. Images of life captured by someone from Wemyss Bight will be utterly different from a rendering produced by someone from Cable Beach. Neither is un-Bahamian. Neither is less valid.

One may resonate with some persons more than others, but they are all Bahamian. The work produced in New York by Bahamian artists is no less Bahamian than that produced in Cockburn Town by a Briton. Bahamian art is expansive. It includes the use of basic ingredients to create local dishes. The refashioning of those dishes to include new flavours and textures allows culinary arts to thrive and grow.

As Bahamians travel and more people come to the country, various influences alter the way conch can be prepared. We can add a twist with coconut, a local fruit that began its Bahamian life as an import but has become a part of the land and its culinary-scape. The way we prepare food is not only historically determined, but also geographically influenced. Hot weather tends to encourage the use of more spices, sugar and salt. This then becomes as much a part of Bahamian cuisine as conch or fish. Sadly, as the population explodes and overfishing threatens the fish and conch stock, we find ourselves in a place where we need to adapt to new ways of using these natural ingredients. We have to change the way we prepare food and the food we prepare. Music is as transformative as visual art. Timothy Rommen’s work in Funky Nassau explores the change in Bahamian music. It also maps out how the shifting culture negatively impacts the production of Bahamian music and its survival. As Rommen points out, the move away from live performances in local venues resulted from a push by hotels to bring local music into lobbies, but it also made Bahamian music begin to die as a popular form.

However, almost every morning as one crosses the bridge from Paradise Island, one can hear the sounds of Rake and Scrape music ascending from the food trucks on Potter’s Cay Dock. This is a part of the culture and art. The more this music is played, the more people identify it with a space and time, and the more familiar they become with it the less likely it is to die out. Cultural shifts through migration are extremely common; from the way we prepare food to the way people speak and then the way oral culture impacts visual culture.

As was evident with the movement of Barbadians to The Bahamas to take up positions as policemen in the colonial days, and with them came a culture of fine tailoring and cricket, so too will the inward move of Chinese and other nationalities influence the visual and culinary culture. It will remain, though, distinctly Bahamian. Each adaptation and new ingredient adds a new layer to an already deeply creolised culture. The light reflects differently in Nassau than it does in London, this in turn impacts the way visual art is produced.

The artist who writes on Harbour Island will have a different relationship with the environment than the artist who writes in Rome and their work will reflect this. The photographer who works in Hawaii will produce distinct art from the photographer who captures images on Crooked Island; the environment really does determine how we imagine art and live culture. So, the tradition of live wells in fishing sloops as all but disappeared in Bahamian culture, and this influences the relationship with the sea and the people. As the population grows, the relationship with space changes. As spaces become gated off from the mainstream, the art that was produced there will change and will be removed from public consciousness.

However, the kind of material available in Mayaguana may not naturally occur anywhere else in the world. This changes the way we live in a space and affects the way art depicts that space. The relationship between a young child from Ross Corner or Peter Street will be different from the relationship of a child from Rock Sound or Palmetto Point, because the geography is different. The same person who moves to Adelaide will then experience a different relationship with the environment. If these young people create art, each will create a different kind of art, be it music, painting or woodwork.

As more Cubans, Haitians and Bahamians of Haitian or Cuban descent grow up and become a part of the landscape, their experiences will allow them to positively influence the growth and expansion of Bahamian art. They will have been exposed to different food and ingredients put together in a different way. The way we live in our environment will also determine how we express our creativity: This is Bahamian art.

I couldn’t have said it better…

Many Bahamians get stuck with Junkanoo, rake and scrape and conch salad defining Bahamian, we are more than that, you so eloquently defined True Bahamian Art. Thank you!

Comments are closed.