Events List

Max and Amos: Enchantment and Magical Realism in Service to Freedom

Reviews of the permanent collection of the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) should always demand an examination of the works and aesthetics of two of the country’s outstanding and prolific indigenous artists, Amos Ferguson (1920-2009) and Maxwell Taylor, better known as “Max”. Ferguson has a particular call on prominence in this regard because it was the Bahamas Government’s purchase of twenty-five of his paintings in 1991 that launched the National Collection.

Sitting Pretty Political: Amos Ferguson and the Reclining Women of Art History

By Natalie Willis One of the key poses for women in classical painting is the reclining nude. It’s become such a huge part of the canon of European historical paintings, no doubt in part to the patriarchal obsession with the naked female form. Nonetheless, it’s been rich territory for many an earth-shattering painting in art history: Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” (1532-34), Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ “Grande Odalisque” (1814), and Manet’s infamous “Olympia” (1865), all of which changed the art world’s reading of the pose each time. It should come to us as no surprise then that Amos Ferguson, our beloved (and often misunderstood) intuitive painter from Exuma, might want to make his own mark in such territory, though perhaps more conservatively given his very religious background.

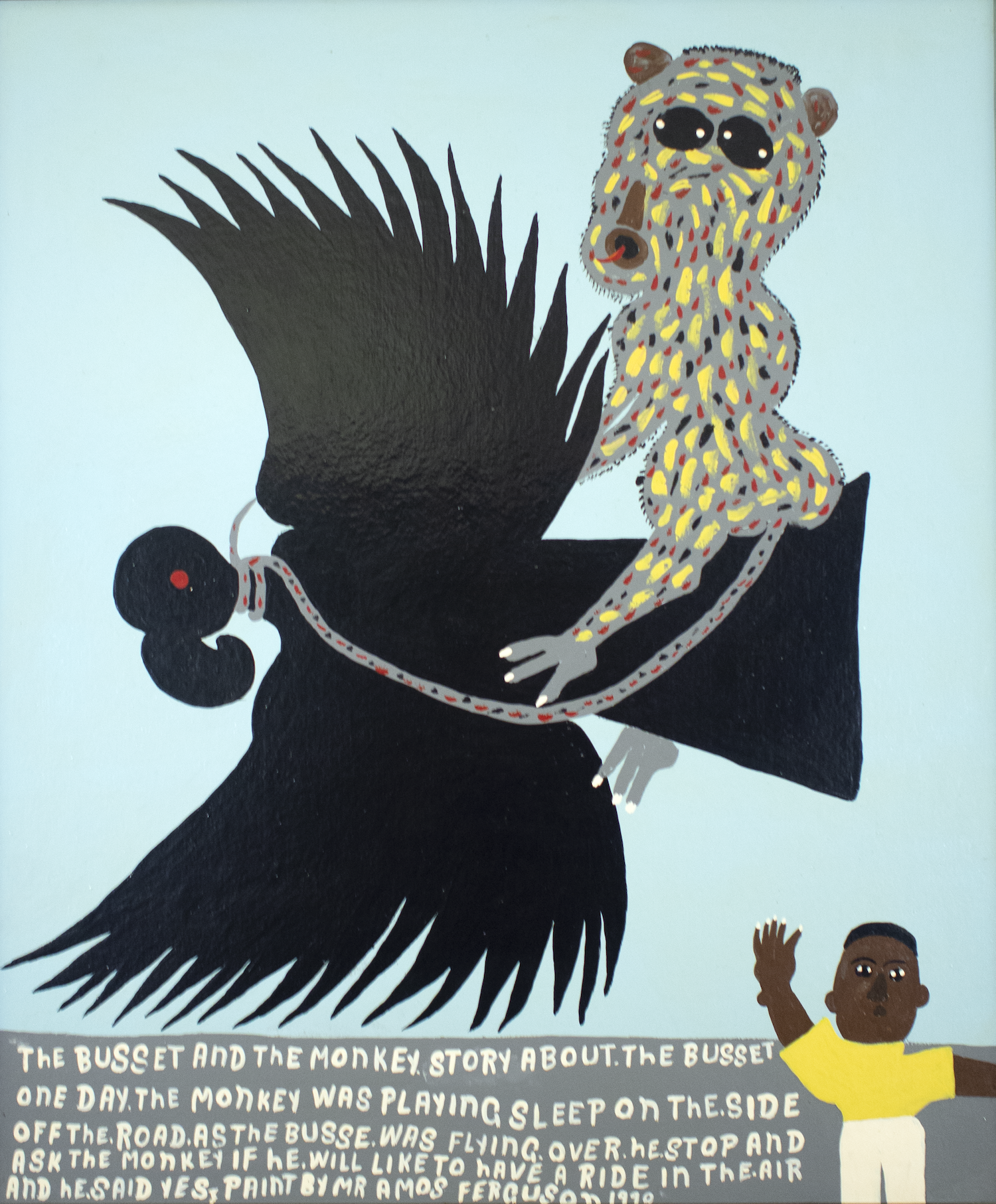

From the Collection: “The Bussett and the Monkey” (1991) by Amos Ferguson

The musical stylings of Bahamian favourite Phil Stubbs, no doubt inspired by the Nat King Cole classic, in this story of the monkey and the buzzard, speak to fable, myth and reality. Amos Ferguson was also quite clearly inspired by this story, as we see in his painting “The Bussett and the Monkey” (1991), currently on display in central Andros as part of the NAGB’s Inter-Island Traveling Exhibition “TRANS: A Migration of Identity”.

The Wisdom of Amos Ferguson: Reflections on “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean”

The Power of Imprisonment through language: The Eye for the Tropics and Majority Rule in The Bahamas

By Dr Ian Bethell Bennett. “We believe that rape is a private matter and that women are inherently unequal.” As 2017 passed into memory this last week, it seems important to think about how we see ourselves in the future. Spirituality could play a large part in this vision, or we could simply choose to continue along what seems to be a road paved with consumerist joy. The paradise myth is part and parcel of that consumerism: where beaches and bodies of paradise that we need to survive can be bought, sold, bartered, negotiated away and given to other sovereign states for their own devices. The opening of “Medium: Practices and Route of Spirituality and Mysticism” at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) on December 14, 2017 presented a moment for reflection, but also for a new focus. When we can celebrate Bahamian ‘masters’ Tony McKay aka “Exuma” or “The Obeah Man,” Amos Ferguson, Wellington Bridgewater and Netica “Nettie” Symonette, along with a boat-load–used intentionally–of other artists, we are saying that perhaps we are changing the way we see ourselves.

Amos Ferguson’s “Jesus and the Good Semeriton” (nd): The Colour of God and Histories of Faith

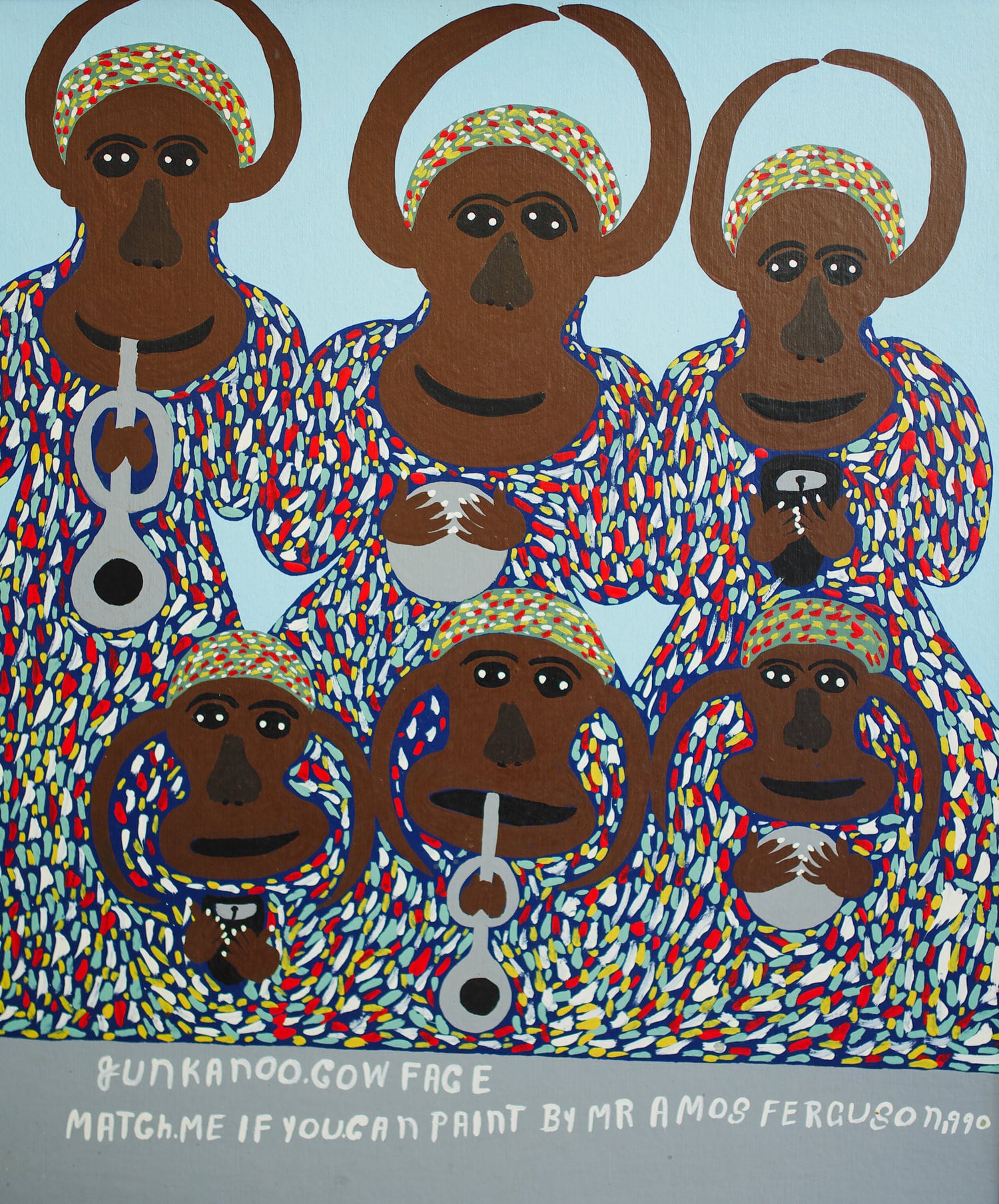

From The Collection: Amos Ferguson’s “Junkanoo Cow Face”

By Natascha Vazquez.

Bahamian artist and icon, Amos Ferguson radiantly portrays the spirit of Junkanoo through an energetic array of repeated imagery and texture in Junkanoo Cow Face – Match Me If You Can, an iconic piece in the Gallery’s National Collection. His interest in flattening the picture plane and depicting a graphic quality to the work is evident in this work, nodding to the style that he became widely known for. Ferguson used colour and repetition of form for impact and clarity. Arrangements of patterns flood his paintings, a visual language closely related to that of Bahamian culture, and in particular Junkanoo.

Ferguson’s Fantastic Dragon: Blending the imagination with the biblical

A fire-breathing hell-beast, a scaly winged thing of fantasy – sometimes good, sometimes dangerous and greedy: Dragons. Not a staple in the established subject matter for Amos Ferguson, but nonetheless a treasure in the National Collection, an entity worthy of having an epic flying reptilian guarding it for sure. Ferguson’s “The Dragon” (1991) is an outlier for a lot of reasons. While his usual practice includes references to biblical scenes, Bahamian folklore, and more often than not, Bahamian scenery – with the iconic titles painted in Bahamian vernacular that act as a mirror for our particular language traditions, this piece doesn’t quite typify his practice.

Amos Ferguson’s Junkanoo Cow Face: Match Me If You Can

The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas was an idea long before it was a reality. Many artworks, therefore, had been purchased and earmarked for the collection before its eventual incarnation in 2003. The Bahamian National Collection, now housed with us in the magnificently restored Villa Doyle, was originally founded on the purchase of 25 Amos Ferguson works.