By Natalie Willis. Elmer Joseph Read, an American artist (b.1860, death date unknown), painted scenes of life in Nassau that provide a strange sense of documentary and fiction. They are stylised images, but the way Read tries to capture his perspective of life in the capital at the time is useful to us for a few reasons. It helps us to see how Nassau has changed over the years, and it also shows us how those who many modern day Bahamians are descended from were seen in that time. So many of the colonial paintings from this time use the iconography of smiling natives, women in headwraps, along with lush greenery and sea-glass ocean water as colonial propaganda. It gave a way to say, “Look how beautiful and safe and bountiful this empire is!” But these sentiments and picturesque ideals aside, uncomfortable as it may be at times, are still things we feel today, albeit in an evolved and shifted form.

All posts tagged: Collection

From the Collection: “Untitled (Balcony House on Market Street)” (ca 1920) by James Osborne “Doc” Sands

By Natalie Willis. There is this assumed romanticism of the past for many, especially when looking the quaint images of Nassau-from-yesteryear. But here, we find it is often laced with a pain of looking at where we were as a nation, those issues we faced then and the echoes of this past that we deal with now. “Untitled (Balcony House on Market Street)” (ca. 1920) by James Osborne “Doc” Sands shows us a Bahamas that is still reeling and reconfiguring after the abolishment of slavery, and post-apprenticeship, even in 1920. The legacy of racial power structures inherited by The Bahamas, and by the wider Caribbean region, was very much present and felt. The tiering of whites, mixed-race, and Black Bahamians is still something we feel today, even with all the work done to dismantle this hegemony.

Angelic Remembrance: Antonius Roberts Memorialises Women of Faith

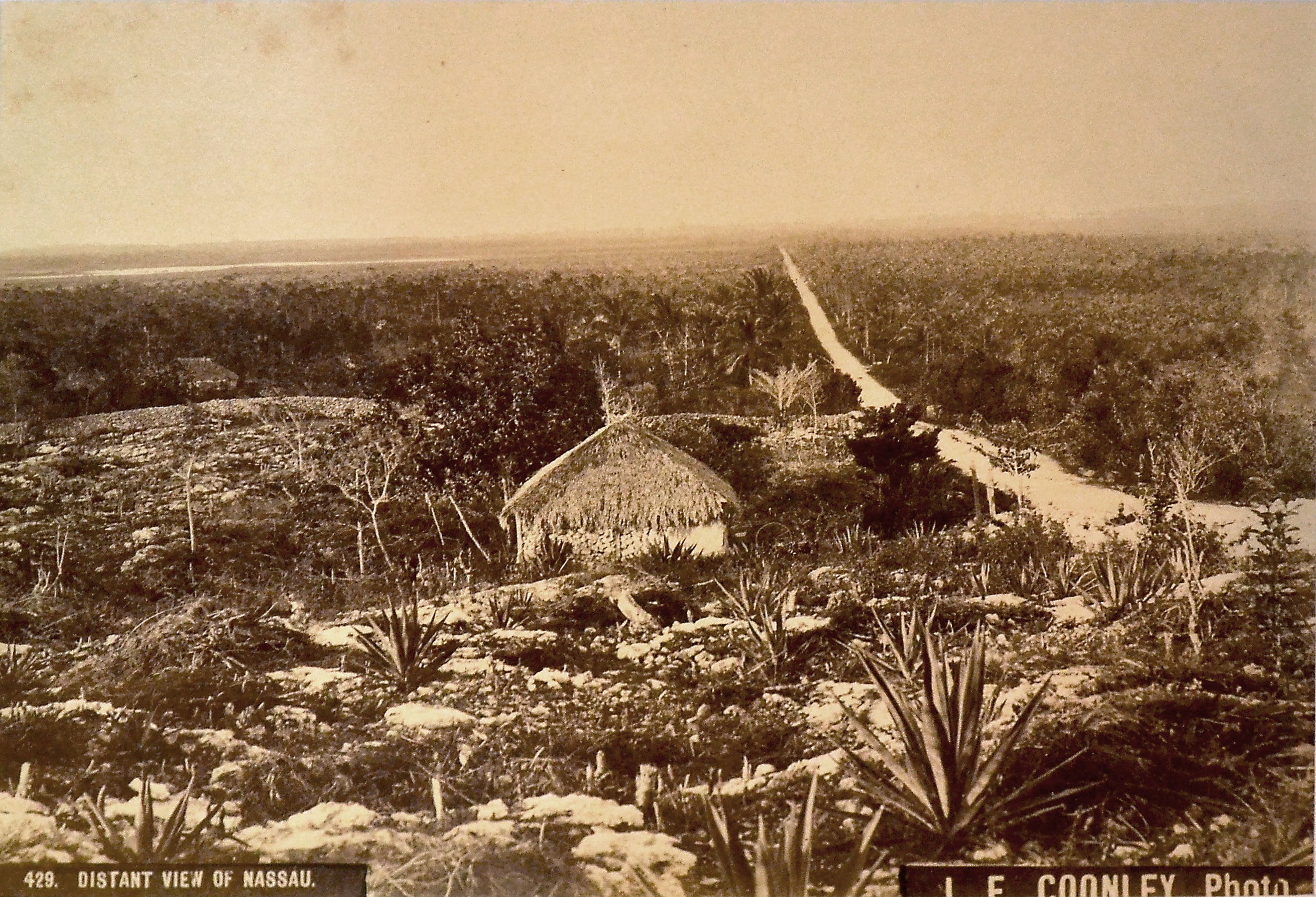

From the Collection: “A Distant View of Nassau” (c.1857-1904) by Jacob F. Coonley

By Natalie Willis. Looking at this photograph, “distant” is certainly apt in different facets of the word. It is a distant, far off view. It is a distant time, a bygone era. It is also a distant idea to think of Nassau in this way – so largely uninhabited with stretches of green bush for miles, sisal and rocky paths to illustrate this difficult land – formerly difficult for our floral inhabitants, now harder for the people living in what feels like harsh social terrain. The reactions witnessed to this image are very telling, the astonishment on locals faces when they try to imagine a Nassau like this seems like having to tell someone to imagine us in prehistoric times, not just over 200 years ago. That surprise speaks to the way the development has become so utterly integral to our identity in the capital, and truly the country as a whole.

From the Collection: Maxwell Taylor’s “The Immigrants No.3” (c1990)

By Natalie Willis. Maxwell Taylor’s woodcut prints are truly a thing of beauty in more ways than the obvious. The stark contrast and drama of a black and white printed image is something to behold in itself, but the way that he incorporates black bodies and the struggles they go through adds a poignant beauty of a different kind. He doesn’t make the struggle pretty, he shows people with the nobility they deserve, migrants included. Using the traditional practice of woodcut printmaking, Taylor’s “The Immigrants No.3” (c.1990) holds just as much meaning now as it did when it was first shown

From the Collection: “Metamorphosis” (1979) by R Brent Malone

By Natalie Willis. There are few artists who were able to evoke the energy of Junkanoo as Brent Malone did. He didn’t just show vibrant costumes swaying lightly: he showed colours and costumes that vibrated, bodies tense with energy and muscles coiled as cowbells get poised to strike, eyes as red as the feathers from that 3 am lap, sweat dripping down faces holding tired red eyes. Malone set out the path for others to display Junkanoo as the manic, feverish, exhausting, and mesmerizing spectacle it is – he made it his mission to show the feeling at the root of the celebration, the cathartic outpour of energy and freedom. It is fitting that he lends this deference of accurate portrayal to a work that means so much to so many: “Metamorphosis” (1979) is a testament to the idea of a nascent Bahamas, the burgeoning forth of a still transforming nation after independence

Living in the Shadows of Empire: Territories of Dark and Light

Remembering our past – navigating our shadowy future. Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett explores the commonalities of post-colonial countries in last Saturday’s “Arts and Culture.”

From the Collection: “Woman With Flamingoes” (1996-97) by R. Brent Malone

By Natalie Willis

It is time to revisit an old favourite with the detail and context it truly deserves. A cross-hatch of brushstrokes, full of the looseness, movement and vibrancy associated with R. Brent Malone’s work, gives way to the key figures from which this piece in the National Collection gets its title. “Woman With Flamingoes” (1996-97), a gift to the Collection donated in memory of Jean Cookson, depicts a flamboyance of flamingoes with a woman staring beyond the frame. Though the flamingoes are bustling and full of movement, she is purposefully still. Malone renders her the focus of the work amidst a pink and crimson cacophony of tropical birds.

The Culture of Space: Places for Art

By : Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

The post office stands at the top of Parliament Street on East Hill street, a monument to 1970s development. It stands now condemned. The Churchill building stands condemned, much like the Rodney Bain Building on the verge of Parliament Street Hill on the way to the post office. Condemned buildings populate the city of Nassau. The shift has been rapid; from a thriving colonial backwater settled by administrators and Loyalists to a post-colonial shadow of colonial rule, to a derelict city of decay. This shift has been enormous.

From the Collection: “On the Way to Market” (ca. 1877-78) by Jacob F. Coonley

“On the Way to Market” (ca. 1877-78) by Jacob Frank Coonley looks to be a work in progress, an experiment, with boxes in the foreground and a window decidedly within the frame of the shot.