By Dr Ian Bethell Bennett

Indigenous culture is being smothered in many areas of the Caribbean and The Bahamas. This erasure has been assisted by a process of deculturation that includes the popular image of Bahamians and Bahamian culture being shifted to reflect an image that is about objectification and imagination. This picture is built on the myth of the exotic. Perhaps the best words to describe this are borrowed from Stark’s “History and Guide to The Bahama Islands” (1891).

The view of Nassau from the sea is very striking, but whether it is the beauty of the situation that impresses the visitor so much, or the fact that everything tropical is strangely fascinating to the unaccustomed beholder, I know not; perhaps it is both. To a person coming from a northern climate, it is like realizing for the first time a picture one has been in the habit of seeing for years in their imagination. (106)

Later on in the text, Stark himself recognises that the early tourist will reap the benefit of seeing and experiencing a place that the later tourist will never see or experience because it has been utterly changed by the arrival of many tourists. This reality of an image entirely altered seems to have been missed by the gentle proponents of creating a picture of us that sells us to them. The Paradise image. Stark’s job is to sell The Bahamas–then referred to as the Bahama Islands–as a good and exotic destination. The focus is on the enjoyment of tourists in the tropics. However, the erasure of what was once Bahamian seems unavoidable.

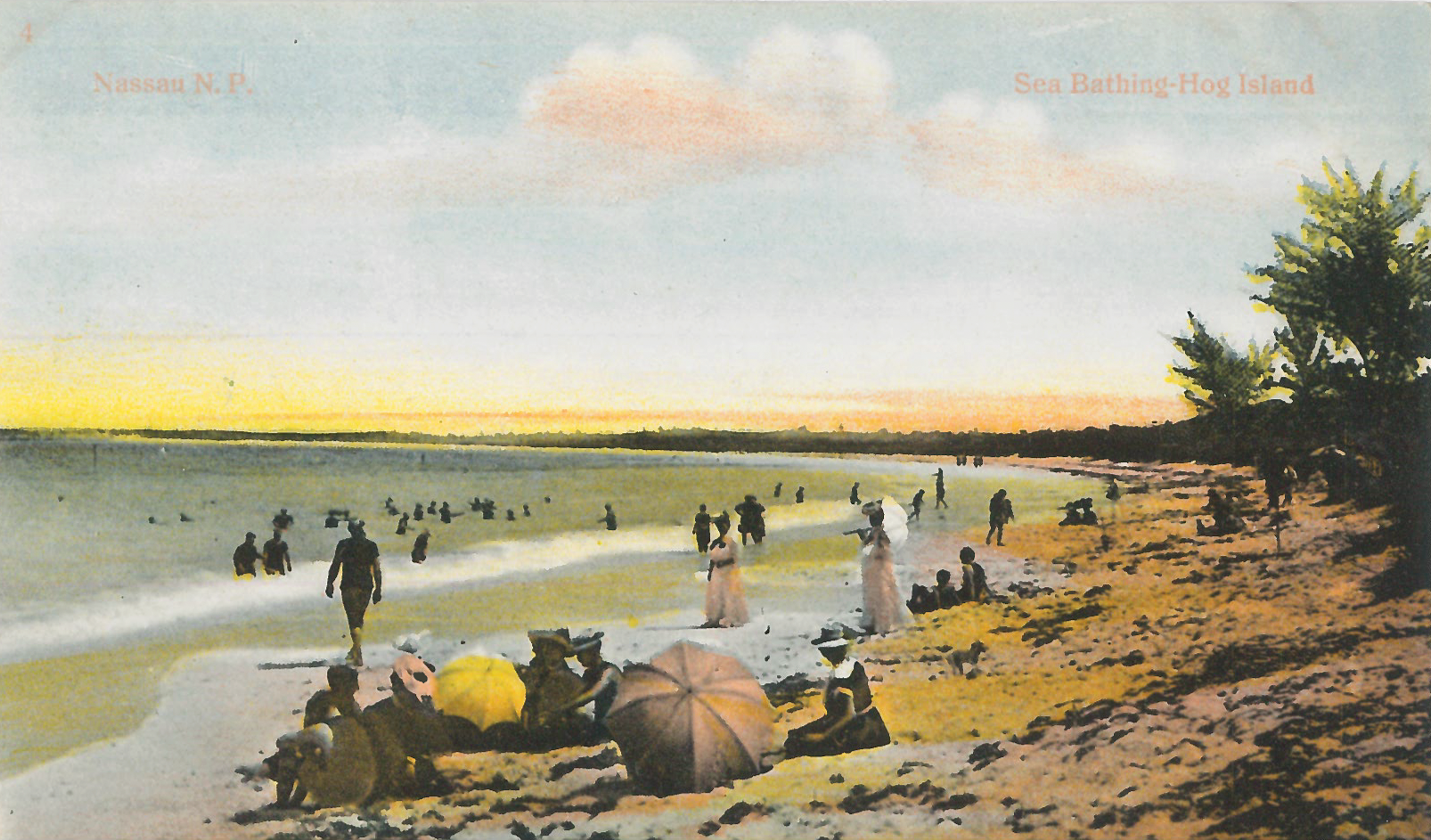

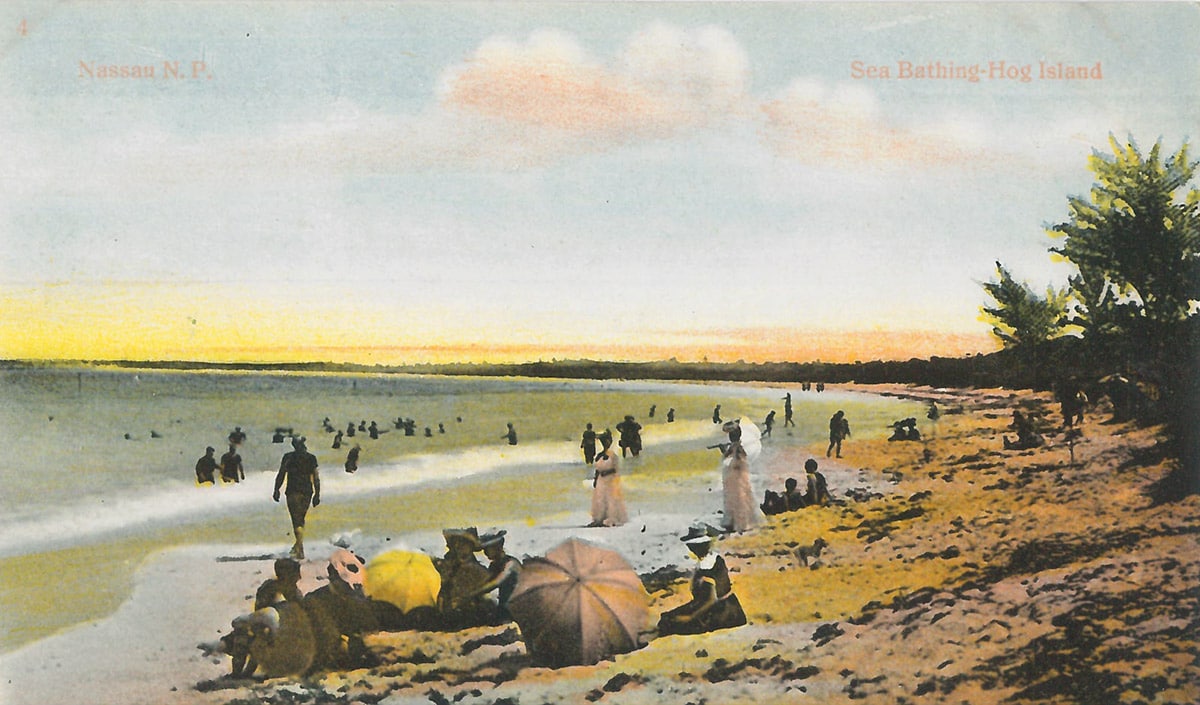

“Sea Bathing – Hog Island” (c.1860-1930), hand-coloured postcard, 3 1/2 x 5 1/2. Part of the National Collection.

As we examine history, displacement and the art of historical representation and disavowal, it seems shocking that we have been so complicit in our disappearance. Our culture, now defined as Junkanoo Carnival, or a Junkanoo that holds a little trace of what it should be seems strangely like a ghost of more sinister efforts to whiten or refocus the lens to show other images of what we expect the tropics to look like.

That said, as culture changes, we understand how we become less visible and less critical, even as the backdrop to a pleasure industry, as Mark Padilla refers to the Caribbean tourist industry. A film, regardless of length, makes us see ourselves differently. When, for example, looking back at Euzhan Palcy’s filmic rendering of Joseph Zobel coming-of-age story “La rue cases nègre” (1950), the film Sugarcane Alley (1983) shows the struggle between development and tradition. The film is haunting and poignant as it mainframes the vanishing voice and cultural memory of working-class Blacks in Martinique during the 1930s.

Our very own Kareem Mortimer and other Caribbean filmmakers and critics have joined the discussion on capturing on the screen a part of the story that is often edited out or elided by images of touristic consumption that we see when we watch “Vers le Sud”/”Heading South” (2005) by Laurent Cantet’s film based on Dany Laferrière’s novel of the same name. The action surrounds a resort where Western women go to find sex in Haiti. The depiction of sex tourism and the horrors of Duvalierism are clear, though usually not in Hollywood. The story is uncomfortable and unkind, but true. We can turn to Cuba and see incredibly rich depictions of life under Fidel Castro in films by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea that are unflattering, but extremely proud of being Cuban, be it the award-winning “Fresa y Chocolate”/”Strawberry and Chocolate” (1993) and “The Last Supper” (1976) and the fabulous “Memories of Underdevelopment” (1968).

Film is a marvellous vehicle for capturing and rendering another side of the story. It can do battle with history through providing access to accounts, as Aimé Cesaire and Édouard Glissant argue. In fact, the need for multiple versions of anything is definite. The Argentinian film “La Historia Official” (1985) is a troubling capturing of the silence around the dirty war that empowered the armed services and was a part of the use of the Shock Doctrine. The later, “House of the Spirits” (1983) is a glitzy, glamorous Hollywood picture that almost misses too much of the story of what happened in Salvador Allende’s assassination and the shift to a US-backed Augusto Pinochet hidden in Allende’s subtext. However, films like “Missing” (1982) that so immortalises the slaughter of the country, voices are never heard if not through these alternative versions that speak our facts and render us visible.

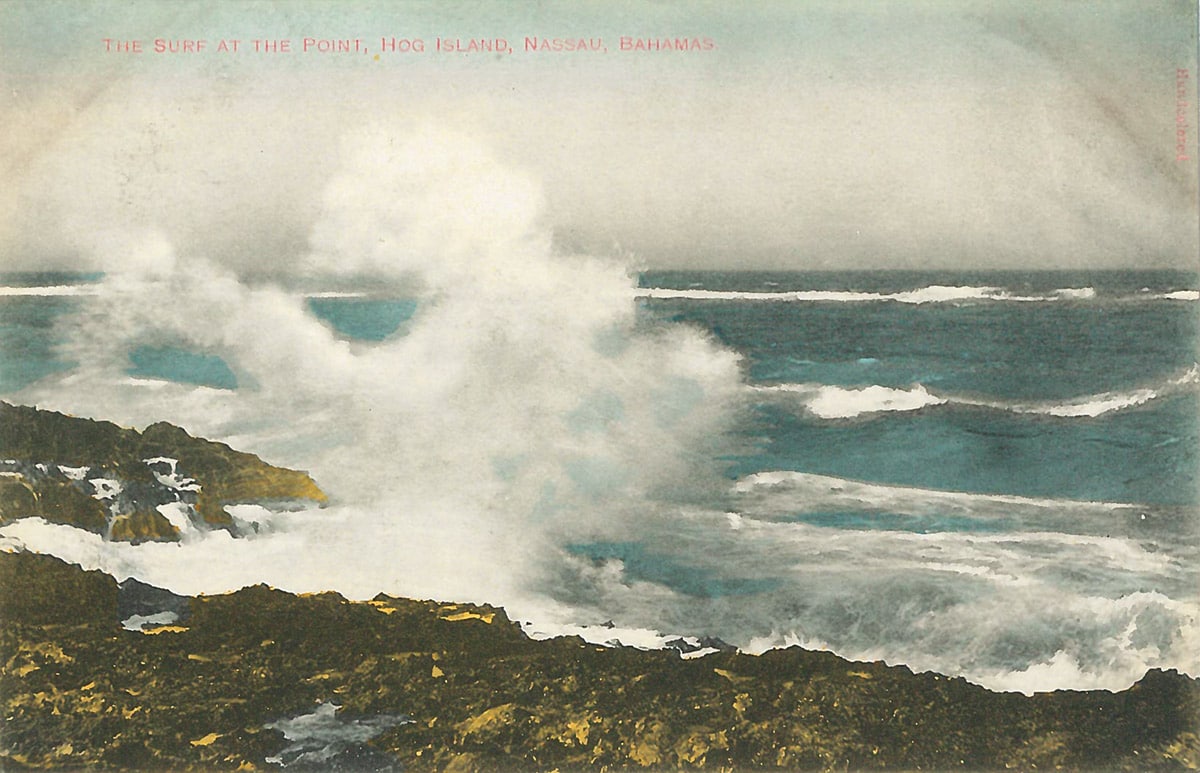

“The Surf at the Point – Hog Island” (c.1860-1930), hand-coloured postcard, 3 1/2 x 5 1/2. Part of the National Collection.

In our Bahamian-made “Cargo” (2017) Mortimer tells the tale that we all know so well, yet no one wants to tackle. Many people are stuck in a spiral of numbers houses and poverty. Haitian smuggling is usually a far more lucrative and larger part of the Bahamian cultural landscape than we would like to admit. The film is not pretty; it does not show the Hollywood side of us, the side where we see James Bond speeding down a pristine road without traffic bordering fabulously calm, blue waters. We see us as we are, all the problematic undergirding that the government hides through doublespeak and boisterous recriminations. It is the story of how we see Haitians, and how they get here. It is the material shift from “simple” migration to the exploitative side of benefiting from the misery of others while criminalising them and scapegoating those we see as evil yet not pointing fingers at the real criminals. The lens is poised and the montage exact. Mortimer brings race, class, ethnicity and exploitative power imbalances into focus in ways similar to Alea’s work. This is a different view of the national discussion that rarely occurs because it is uncomfortable and prickly.

The Island House Film Festival produced by Lauren Holowesko and curated by Mortimer provides access to harder to see smaller budget and independent films. In many filmic representations, we know The Bahamas in the tropical image created for the screen. The image tells one story of spaces and lives not visible to the mainstream lens, much like the work in “Ver Le Sud”, which shows the struggles of the sex workers in tourism, the discourse is harsh but slightly softened by the camera, and the indirect manner in which it presents a reality that is just beneath the surface allows discussion. As the tropical image circulates, the discussion about repatriating “Haitians” who are born in The Bahamas but used as cannon fodder goes on. Their nationality is denied to them and the reality as to why people spend their last dollar and become indebted to leave their nation to set up in another place where they are treated as less than human is eclipsed from the frame. The discussion about Duvalierism, about the macoutes, the reality of rape, torture and murder is not shared with the new generation who have been educated in the image of paradise but not seeing the underside, even though many of them live cheek to jowl with that underbelly.

The beauty of pristine beaches sold to a world beyond our shores that changes the geography of home, the physical space of land and the spatially-determined identity is so appealing that we become victims of the hype and caught up in the fiction of paradise. Film is somehow less invasive than writing and so can influence from close without jarring too drastically, though telling the stories of those the paradise myth is built on but does not see.