By Natalie Willis.

Regional engagement is key to developing the arts ecology in The Bahamas. This historic hurricane season has shown us that the Caribbean is far stronger united than apart, and that we must look to our archipelagic family of island-nations to support us when the rest of the world might not quite feel so compelled. The Double Dutch series of exhibitions is our way of extending that notion of camaraderie and union, the coming together of different artists to show how we are a Caribbean full of places that, while similar given the history, still hold very unique practices and cultures and ideas of self. This newest iteration of the playful, two-person show brings Dede Brown into the fold as our Bahamian contingent, known for her vivid and beautiful material explorations in space (think: the aluminium flamingos at the airport), and paired with her is Dominican-American artist Joiri Minaya and her intriguing explorations into identity and Otherness.

“Re: Encounter” is named so for the back and forth between the artists and this idea of discovery: of self and of land. Days after the (recently renamed) Discovery Day – what we now know here as National Heroes Day – the artists have each taken their own spin on ideas of discovery and encountering self and space.

Brown, formally trained in interior design before she began to seriously embark on her art practice. This most recent installation in the ballroom for the Double Dutch is developed from a series of work that was born in Switzerland of all places, where she stayed with friends who happened to run a mental health support space.

Brown expands,“They basically cater to people who are having different mental health issues and giving them a space where they can deal with their problems. Being around that and thinking about people and their struggles made me think about how we all have mental health issues and struggles we don’t talk about.”

We are no strangers to this here. Though it is of course all speculation until we can get the infrastructure to get proper statistical data collection in place, I would argue that mental health issues in the Caribbean are staggeringly high given the difficult space we live in, the difficulties we have with identity in general, and the complex history we have inherited. The hurricanes, historical trauma and broken economy we live in are all contributing to high rates of depression and anxiety going undiagnosed and untreated. We are a strong people. There’s no doubt about it, given the fact we are still here ploughing on in spite of it all. However, functioning does not necessarily mean we have a good general state of public wellbeing when there is a lot of suffering going on with little chance for relief. No wonder then that Brown might be drawn to these ideas.

“Sometimes it’s a chemical imbalance, sometimes it’s trauma: all of these things that nobody ever wants to discuss. For my work, it offset this idea of talking about human behavior, human perception, that tension and awkwardness we never want to deal with. So I took these ideas and experiences and started with this form of the human head, this bust, and naturally it became more feminine as I was thinking through my own place in this. Afterward they developed to be a bit more ambiguous, a little alien and androgynous, I want my work to reach a wider audience so I left it more open to interpretation so that you could insert yourself into the figures.”

Brown has been working with these figures for almost two years, and her playful experimentations with space are indicative of her background in design – that, and the variations in pattern and material that make up the busts floating around the upper gallery.

Where Brown deals with discovery of self and identity, (particularly given her difficulties with being distinguished as Bahamian given her European ancestry and the unfortunate stereotyping here of Whiteness automatically registering as “tourist”), Minaya deals with discovery in regards to our colonial history.

Presenting three works for us, Minaya deals directly in the idea of “encounter” as the first encounter the region had with the Western world. Through critique of ideas of the “tropical” as it was produced in the 1800s, and the legacy of our first wave of colonial history here with The Bahamas being the site of the first landfall of the (in)famous Christopher Columbus, she is also directly dealing with ideas of identity but through the lens of post-colonial discourse rather than psychology and self.

Minaya has built a wall in the gallery to divide the space, and this fabric-covered, imagined-tropical wall of material obscures the view of a video work dealing with the past and present of our colonial history.

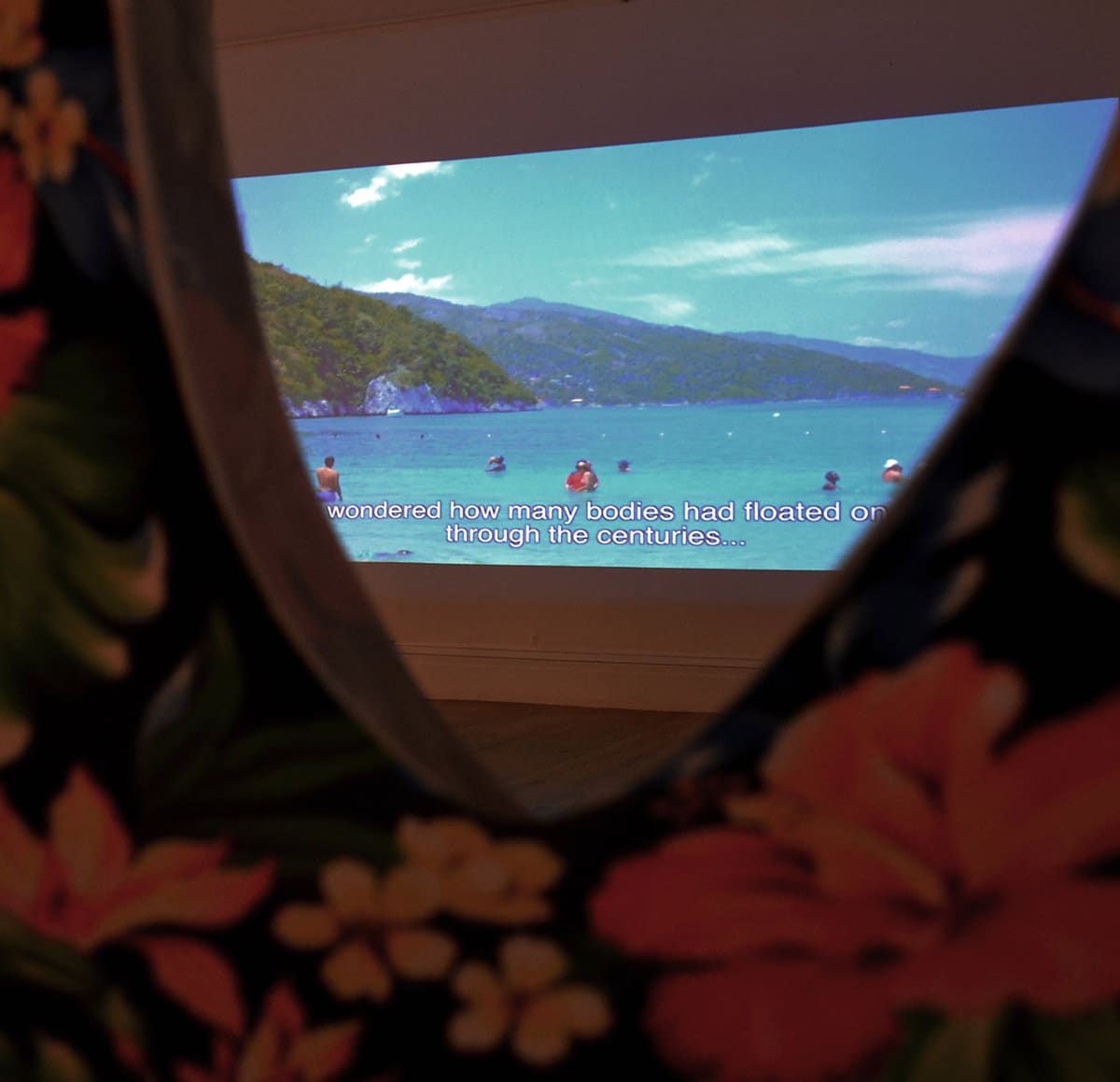

“Labadee” (2017), a video work being presented to play alongside Brown’s “Tesselations (Pieces of you, Pieces of Me),” 2017, is at once disturbing and beautiful as it deals with the landscape and the difficult history around it. “The video came out of footage that I recorded when I first went on a cruise 2 years ago with my family, and Labadee was the most striking for me because it’s a beach in Haiti that is leased until 2050 by Royal Caribbean and has been under their management since the 1970s so it has been like this for a while.”

The work shows Minaya’s exploration of the space, being Dominican she is quite accustomed to the beauty of beaches in the region, so she set off to “explore” and came across an unsettling encounter.

“I wandered around the area and found that beyond this really boring building with bathrooms there’s a wall, and on top of that wall is a fence that blocks off a road and there’s people walking, buses, people just going about their business. But just beyond that is a hill with boys and young people waving empty plates at you so you would give them food from the buffet. I understand that could be performative to a certain extent, it’s possible that they aren’t starving and depending on a cruise to dock to give them food, maybe they just do that whenever there’s a cruise and they have other forms of sustenance. However, seeing it and being on a literal fence and this side of the fence was awkward and convoluted on many levels – I’m Dominican, I’m in Haiti, and I’m contending with this. It really stuck with me.”

The legacies of two different waves of colonial past are very much embedded in the physicality of the landscape here – the way it was “produced” to be an idyllic Eden for the West – and in the way the land is managed. A story we all know too well, and Minaya plays very directly with the history, though it might not seem apparent at first.

“The video has subtitles throughout that are mostly narrating my thoughts on this encounter, but the first few subtitles are actually borrowed from Christopher Columbus’ diary. They are taken from when they first saw land, and you see these subtitles against footage of the sea and the cruise and the cruise starts docking and you start seeing footage of Labadee and it’s like a historic and contemporary dialogue of being on the water in a boat and navigating the Caribbean. Trying to do a parallel between historic types of oppression and these contemporary situations which are almost an extension of, to me, the same thing.”

This play between thinking directly of self as a contained being in Brown’s work, trying to muddle through and sort out our emotions and mental wellbeing, begins to get a direct tie to the colonial trauma that Minaya unpacks and plays with in her works. Interaction became key for both artists, as Brown makes viewers move around the space and engage with what were initially wall-based objects that have embraced their simultaneous 2D and 3D nature by suspending them from the ceiling for better investigation of the contents that spill forth from the figures, and Minaya forces viewers to contend with her hyper-tropical fabric wall to engage with “Labadee,” (2017).

“After conversations with Dede on my previous work with the bodysuits, it had me thinking about how I could take this idea and think about this for the Double Dutch, and we were thinking about how to lay out this space and it got me thinking about the wall from Labadee, and I decided to use spandex tropical fabric as a way to build a wall that people have to interact with in some way, to get to the video – to transgress the space, to crawl through the holes in the wall, some kind of tension to get through to the other side. It’s a choice, but it’s also a sort of privilege. You can come in and out freely, its playful, it’s not a critical-economic situation you’re being put in like the boys in the video.”

This collaboration between Brown and Minaya is what Double Dutch is all about, it is key to understanding ourselves and our particular geography and history and its effects on the collective Caribbean psyche. Opening up discussions such as these helps us to get clearer focus on what really are two sides of the same coin. “Re: Encounter” will be on display in the ballroom of the NAGB from October 13th through to November 12th, 2017.