One of the great joys and privileges of working in the art field is the necessity of travel to meet colleagues, see exhibitions, do studio visits and, most importantly, create the networks necessary to support our artists. In the Caribbean region, this is even more important since we are—by our natures as island nations—more apart than together in terms of a regional identity. Exchanges—between artists, curators, writers and other professionals—are an incredibly important way to continue increasing one’s professional knowledge and also to disseminate information on what is happening in one’s home country to the outside world.

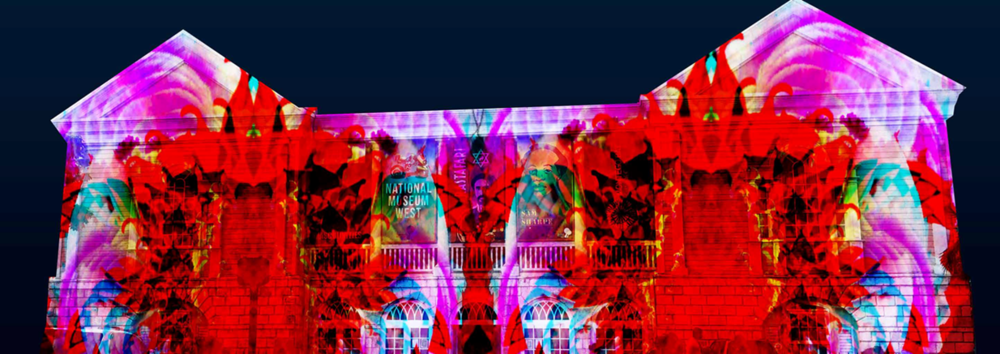

Facade, National Art gallery of Jamaica, Kingston

It was a delight, therefore, when The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas was invited by The National Art Gallery of Jamaica (NGJ) to be a participant as a selector for their upcoming Biennial, giving us the opportunity to do research into contemporary artistic production in Jamaica, learn more about their history and development as a national institution, and forge closer bonds with our colleagues.

Firstly, it is always interesting to compare and contrast one’s institutional history with that of one’s peers. The National Gallery of Jamaica was founded in 1974 in Kingston and is the oldest and largest public art museum in the Anglophone Caribbean. Having started out in an historic home, Devon House (not unlike NAGB’s Villa Doyle), the challenges of a domestic space proved difficult to manage and it moved, in 1982, to an unused department store of modern and spacious design, and currently has a massive 30,000 square feet of exhibition space (compared to NAGB’s 4,500 sq.ft), not including their annex, NGJ West, in Montego Bay (3,500 sq.ft).

The NGJ has a comprehensive collection of early, modern and contemporary art from Jamaica, along with smaller Caribbean and international holdings, an extremely interesting divergence from our mandate at the NAGB, which focuses on solely Bahamian art. The NGJ is a division of the Institute of Jamaica, Ministry of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport, the title of which also speaks to more inclusivity.

A significant part of the NGJ’s collections is on permanent view and being able to look at a range of works—from wooden Taino artefacts; to oil portraits of aloof Englishmen, from the late 1700’s; to the stunning Isaac Mendes Belisario hand-coloured prints of their “John Canoe” (1837-38); to modern paintings from both Jamaica and other countries—certainly gives the visitor a much broader and firmer foundation and context in which to view local production. It does pose the questions as to how “national” a National Gallery must be: can one truly understand one’s artistic output without looking at work by others and understanding the full range of global history in the arts? Can you understand Max Taylor without having looked at African tribal masks or Picasso’s early Cubist period? Must being “national” translate into being exclusive and non-inclusive?

Interior view with tour group at National Art Gallery of Jamaica.

The NGJ has an active exhibition programme, which includes retrospectives, thematic exhibitions, guest-curated exhibitions, and touring exhibitions that originate outside of the islands. The NAGB can say the same and, conversely, the plus side of not having a huge historical collection to take up space and time to care for means that we can stage more local shows. Comparatively, the NAGB has a high turnover, which has translated into increased local buy-in. So, as one sees there are pros and cons.

The NGJ’s flagship exhibition is the fairly recently re-branded Jamaica Biennial. This event was birthed in 1977, inaugurated as the Annual National Exhibition, not unlike our national exhibitions, such as that currently on show at the NAGB (NE8), which is generally an open call survey show. Having existed for 25 years, the Jamaica’s Annual National show became the premier art exhibition in Jamaica, although it comes with some challenges. In the early days of the growing art scene, it was extremely important to encourage people to dedicate themselves to art and, as such, to support all attempts. The net was cast wide and, as artists reached a certain level of technical achievement, they were given a lifetime invitation. While this might have been a wonderful idea in the early days, the legacy of the initiative poses great challenges today, where a very long list of lifetime invitees must be curated into the juried section. Some of these invited artists may have given up a regular practise, even, and it makes a cohesive single exhibition almost impossible to pull off.

At Devon House, one of the locations for Jamaica Biennial 2017, with NGJ Director Veerle Poupeye (2nd left, back) and the 2017 selection committee, from left to right: Suzanne Fredericks, Amanda Coulson (bottom centre), Chris Cozier (to centre) and Omari Ra (far right)

While the NAGB does not have this particular problem, we have still struggled with the issue of the National Exhibition and what that should mean. Should some “special” artists be invited and not subject to a juried selection? How does one make a sensible, unfolding exhibition with a clear direction out of 100 disparate works? For some editions, a theme was selected to try to curate an exhibition that created a parcours and told a clear story, so the viewer was not presented with a large, random selection of works that had no relationship to one another; sometimes this worked and sometimes it did not.

Also: who should be considered “Bahamian”? Should the show be open to expats resident here and, if so, for how long must one be resident to be considered an integral part of the Bahamian art scene? What about diasporic artists? How many generations may one go back to consider a US or Canada-based artists “Bahamian”?

David Gumbs, project for projection on facade of National Gallery of Jamaica West, Montego Bay, Jamaica Biennial 2017.

Jamaica has also struggled with these questions and is moving forward in a very open and inclusive way, which is admirable. In 2002, their Annual National Exhibition was converted into the National Biennial and, effective 2014; it was renamed the Jamaica Biennial. The 2014 edition kept many aspects of the established framework for previous Biennials but with some important changes, to create a more dynamic biennial that both acknowledges the growing regional and international networks within which Jamaican artists participate and still supports the best of local art production. While it is an exhibition of current art, the Jamaica Biennial is committed to aesthetic and cultural diversity: it includes contemporary, traditional and popular art in all media, styles, genres and features new, emerging and established artists. In fact, a Bahamian artist—Blue Curry—was invited to be part of this exhibition in 2014, with an open-air installation in Downtown Kingston, the vestiges of which are still visible.

Amanda Coulson, Director of the NAGB, was present on the panel of four judges for the 2017 juried section, along with Trinidadian artist, writer and curator Christopher Cozier, and two locals in the persons of artist, art lecturer and head of the Fine Arts department at the School of Visual Arts of the Edna Manley College, Omari Ra, and art dealer, curator and art auction organizer, Suzanne Fredericks. The judging took place at the NGJ on January 9th -11th and the selection panel reviewed 175 works by 110 artists, of which 65 works by 47 artists were accepted.

In addition, select international and regional artists are invited to do special projects during the exhibition—these include Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons (Cuba), Andrea Chung (US, of Jamaican/Chinese and Trinidadian descent), David Gumbs (St. Maarten), Nadia Huggins (St. Vincent & The Grenadines), Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow (Jamaica), Raquel Paiewonsky (Dominican Republic), and Marcel Pinas (Suriname)—which is a wonderful development.

Remnants of Blue Curry’s intervention from the Jamaica Biennial 2014

Such presence increases dialogue between local and visiting artists, and more importantly for the home base, will bring attention to the exhibition from a greater range of locations, press, and public, exposing Jamaican artists to a broader international audience. The exhibition will also contain two special tributes to major Jamaican artists. The Biennial is thus a hybrid between a curated, invitational and submission-based exhibition, which the curatorial team of NGJ—consisting of Director Veerle Poupeye; O’Neil Lawrence, andAssistant Curator. Monique Barnett-Davidson—must craft into a cohesive whole.

Even with their 30,000 sq. ft. of space, just like here—where we have collaborated with Hillside House in order to extend the possibilities of our own NE—the Jamaica Biennial 2017 will be shown at the NGJ and at Devon House in Kingston, as well as at National Gallery West in Montego Bay, with additional venues in Kingston to be announced. The Jamaica Biennial 2017 will open with a series of events from Friday, February 24 to Sunday, February 26, 2017, and will continue until Sunday, May 28, 2017.

The future vision is for the Jamaica Biennial to be visibly positioned on the international art calendar as a Caribbean-focused biennial. Discussions have started to do this in collaboration with other public art museums and art organizations in the Caribbean, such as the NAGB, by creating a coordinated itinerary to make our region an unmissable destination for art and culture.