Currently browsing: Stories

Amos Ferguson’s “Jesus and the Good Semeriton” (nd): The Colour of God and Histories of Faith

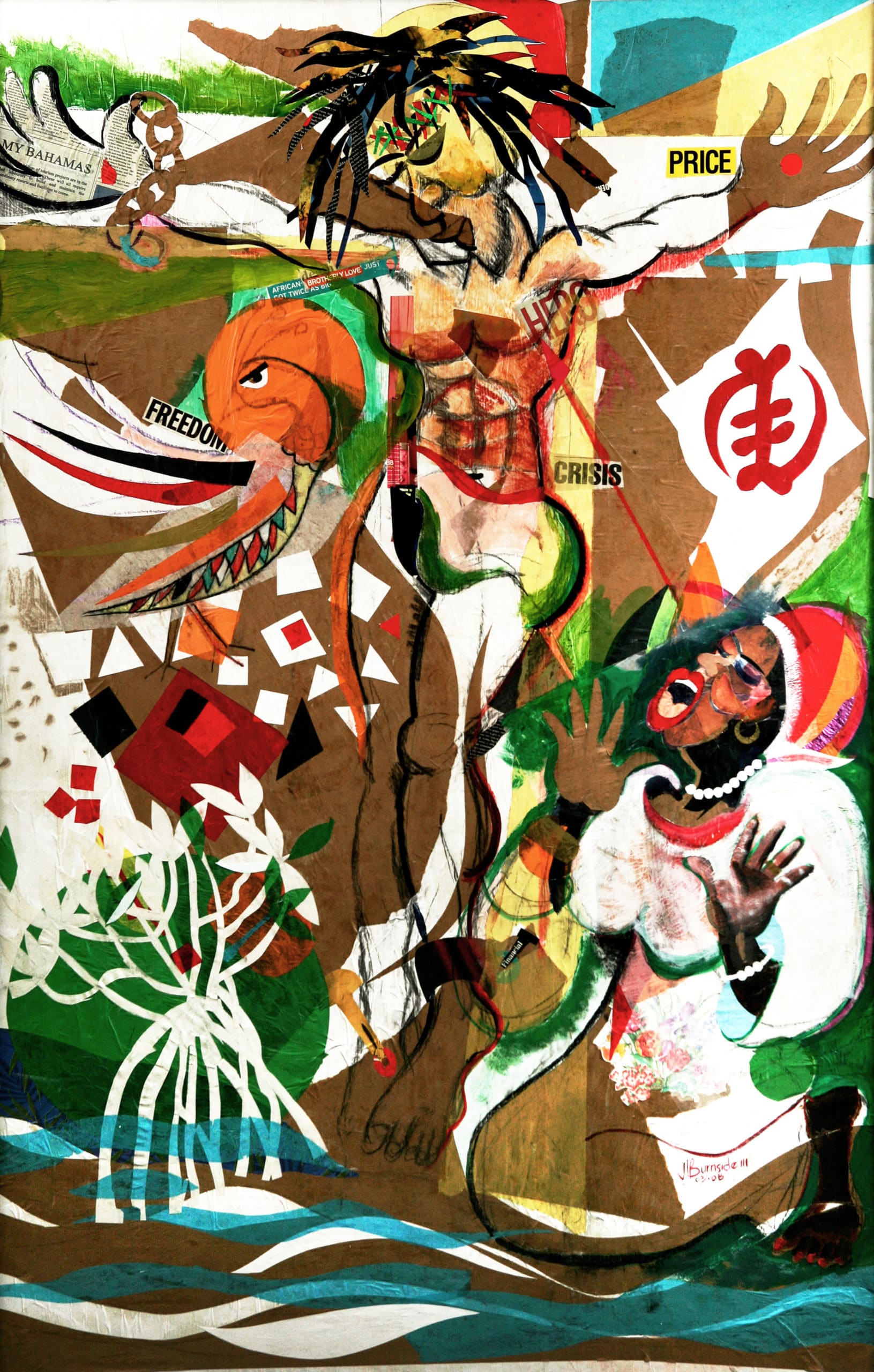

A Glitch in Time: Who’s in for the Saving?

Angelic Remembrance: Antonius Roberts’ memorialises women of faith

Sitting with the Dead: “Medium,” a show of Bahamian Religion and Spirituality

By Dr Ian Bethell Bennett. Tie a black piece of cotton around the child’s wrist, Don’t walk outside at night without covering the child’s head, Be careful how you come into the house at night, Wipe your feet off well. Cover the mirrors with cloth, Open the house if the coffin comes by, let the spirit travel through, Rosemary helps keep away bad-minded things… To our mind, these are all local lore. To many, these are discredited as they are lumped together with Obeah and dismissed as ‘evil, black, Dark and African.’ Our double-consciousness denies the survival or the importance of such cultural elements as Asue, Lodges, Burial Societies, Friendly Societies, all of which allowed our spiritual and physical survival during and after slavery.

Seeking Divine Creativity: Allan Wallace’s new works revisits his religious upbringing

Golden Touch and Go: Jace McKinney’s imagines golden kings and living dangerously in “Trumped” (2013)

Unpacking Identity with Joiri Minaya

The sixth iteration of Double Dutch “Re: Encounter,” featuring the works of Dede Brown and Joiri Minaya, starts to address how important it is from a curatorial perspective to provide opportunities for artists, who are looking for ways to mitigate the sense of frustration that they feel within their practice, by allowing a moment to experiment. The following is the first in a two-part series of long-form Q+As that seeks to expand upon both projects. We connect with Joiri Minaya, a Dominican-American multi-disciplinary artist whose work deals with identity, otherness, self-consciousness and displacement.

Creative Youth: Reevaluating Our Values and the Work of Young People

By Dr Ian Bethell Bennett. The Bahamas has quickly become a country with multilayered and multifaceted youth conflicts. Over the last ten years, these issues have taken the fore and removed the focus from real and positive change. Violence, youth disengagement and youth disaffection can be addressed through creative expression and creative practice. However, in a school system that argues for a focus on the STEM and not STEAM, but without any real engagement–where art and performance are seen as outside and unwanted stepchildren–it is significant that some young Bahamians are excelling in their work and their creative expression.

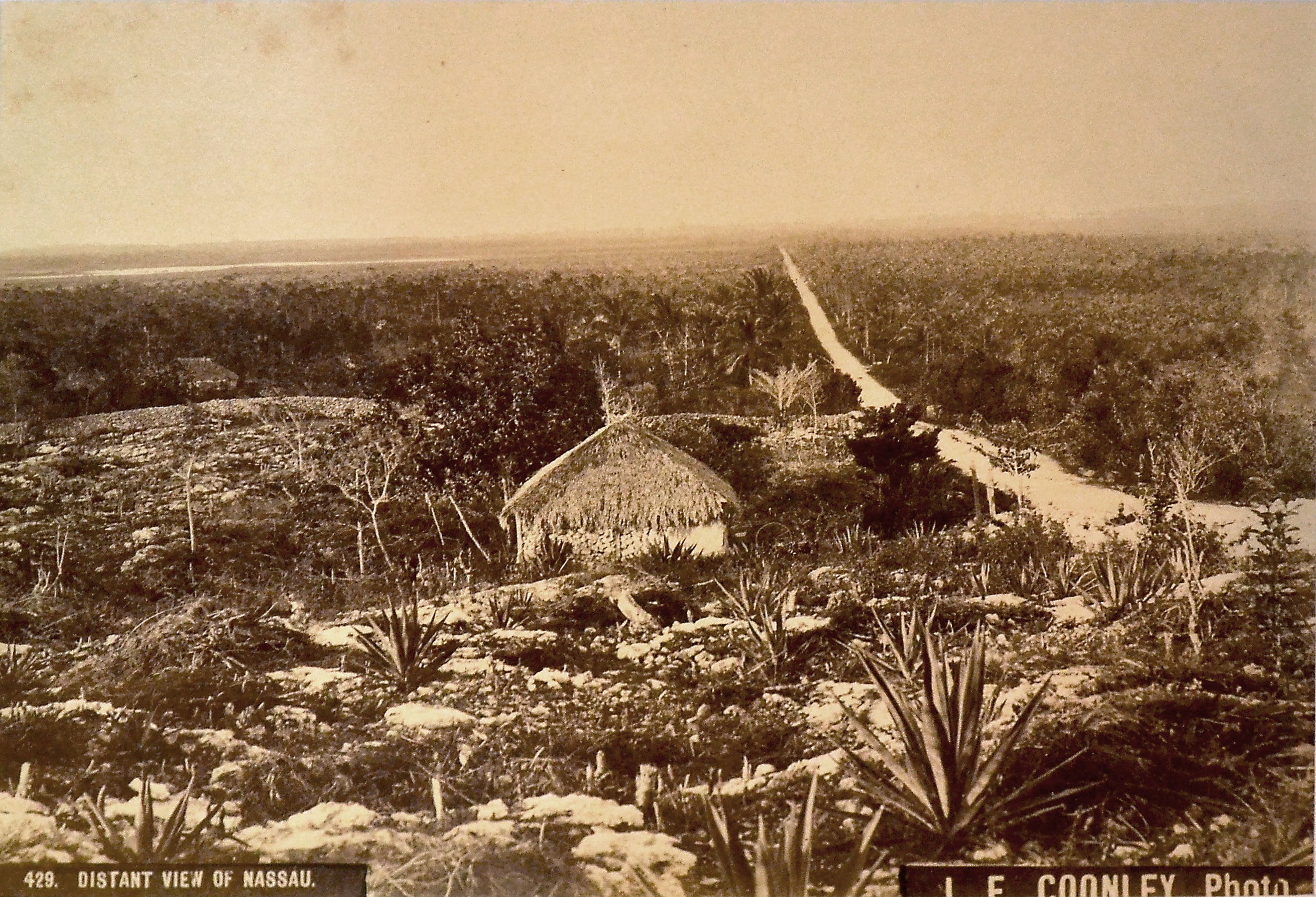

From the Collection: “A Distant View of Nassau” (c.1857-1904) by Jacob F. Coonley

By Natalie Willis. Looking at this photograph, “distant” is certainly apt in different facets of the word. It is a distant, far off view. It is a distant time, a bygone era. It is also a distant idea to think of Nassau in this way – so largely uninhabited with stretches of green bush for miles, sisal and rocky paths to illustrate this difficult land – formerly difficult for our floral inhabitants, now harder for the people living in what feels like harsh social terrain. The reactions witnessed to this image are very telling, the astonishment on locals faces when they try to imagine a Nassau like this seems like having to tell someone to imagine us in prehistoric times, not just over 200 years ago. That surprise speaks to the way the development has become so utterly integral to our identity in the capital, and truly the country as a whole.