By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

Beauty surrounds us. Waters flow over us. Sands, pink, grey, white, beige provide support for life. Mangroves with their gaseous smells and nursery roots, sustain coastal health as they prevent full-on impact from storm surges and hurricanes. Art provides a salient view into these natural beauties and the past, as it also imports past ideas into the present. It inspires and it heals. In the early days of tourism in the colony, people came to be healed in the balmy tropics The Bahamas offered. Some in turn captured and marketed this. Others were here and transported the feeling of the space to other shores through their visual and literary experiences. The Bahamas is known for its natural beauty: the way the sun strikes the waves and refracts into the eye of the beholder. This natural beauty is fragile, though it seem everlasting.

Harry Leslie Hoffman, a Pennsylvania-born artist, captures much of the vibrancy and beauty of Bahamian seascape and underwater world. For this he needed clean air and seas, as articulated last week. Again, the beauty of the natural environment should not be constricted by the built environment’s encroachment on it. As we experience the shifting tides of change and development in our lives, the capitalist concept of controlling space and engineering it to fit into an idea that is foreign to that place is dangerous as it shifts concepts and relationships. When we think of development and its balance with loving the natural environment, we must look to visual art and literature and their relationships with the ways we experience beauty and nature. Out of these artistic traditions come artists like Eddie Minnis and Brent Malone, to name only two. However, there can be no line drawn between “inside” and “outside” art because so much art and so many of the artists who would have wintered or ‘springed’ in the Bahamas would have influenced children with whom they had peripheral or direct contact.

Young Bahamians could have been encouraged by the presence of visitors painting on Bay Street or Over-the-Hill. They might have seen scenes from movies shot here. Many were the days of walking past Minnis as he sat or stood and painted trees, houses, scenes. In an earlier period, such would have been the case with Gaspard Le Marchant Tupper, Hartwell Leon Woodcock and Hildegarde Hamilton. We must discuss these works and their value in the way they interpret and present the Bahamian landscape, and as they appreciate a side of life that would have been so important to our own experiences. This view is often seen as feminised, as any appreciation of beauty and nature, is always already termed feminine by masculinist understanding of nature as a space to be concurred rather than protected or valued. Yet we must live in harmony with the environment or it and we die.

Today, we see a proliferation of images that have masculinised our view of the environment. In part, this is a process that sees nature as inferior and feminine that must be altered to fit that consumerist image of progress. So, the beauty that was valued in art, is denigrated by the state’s discourse of progress and success. Success is no longer attracting one million high-spending tourists who seek beauty and nature in paradise. Instead, paradise must be managed into the space of industrialisation that, as in the case of Louisiana and the BP Oil spill, is damaged. No one in any of those communities wanted, expected or planned for that oil spill that changed life ways.

The current view

When we visit Cabbage Beach, we can already see the degenerative impact of mass tourism and overconsumption on the beach and its environs. The degradation of the dunes, littered with refuse, broken-down beach chairs, umbrellas and debris from hurricanes and tidal incursions is obvious. This is not casting blame, nor is it the responsibility of the vendors, or the untrustworthy, as we are like to complain. It is a serious lack of conservationist ideation, planning, and implementation, a joined up process that maintains tourism and natural beauty by managing our natural assets as well as the built environment. There was never any mitigation plan to deal with this kind of massive scale tourism impact. The beauty that our archipelago holds, as seen in the eyes on The Bahamas from international artists, filmmakers and pleasure seekers, is extremely fragile, yet quickly unseen or written over by damage—unintended as it may be—of progress. Reflection and experimentation before implementation are essential if we want to balance the pace of progress with living in what we see as making it ‘Better in The Bahamas”. Yet tourism says nothing about destroying the environment, though it be its lifeblood.

The need to industrialise this natural reserve seems to present itself as the best and only option that can ‘rescue’ the country from its current state. It disregards the beauty and nature fundamental to the country’s and especially that island’s life. The beauty captured by Hildegarde Hamilton in Nassau, Eddie Minnis in Harbour Island and Eleuthera, and Gaspard Le Marchant Tupper in New Providence has been cast as antagonistic, contrapuntal to and against progress. Indeed, these images need to be understood for their confluence, not antipathy.

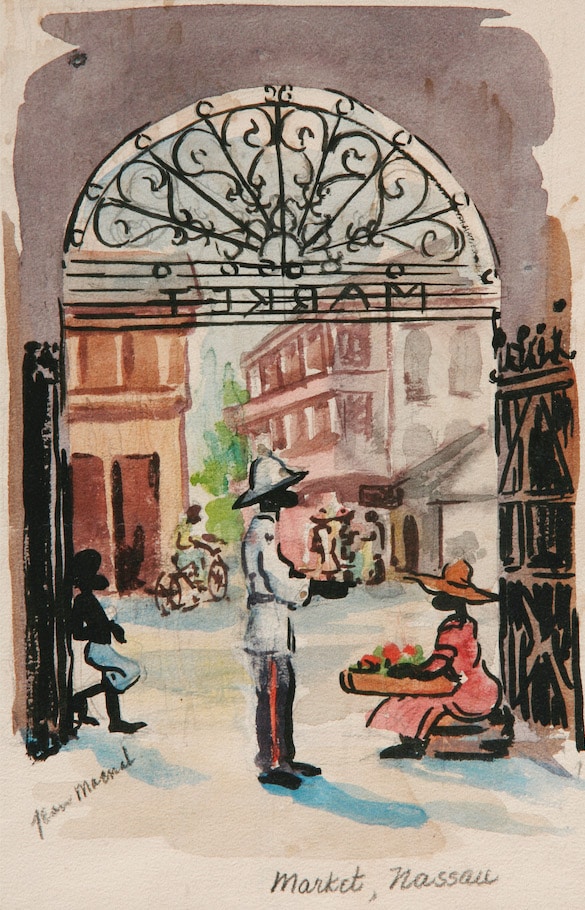

Jean McNab. Market, Nassau. Image courtesy of Dawn Davies

Similarly, The Bahamas now has incredible opportunities to develop a forward looking development model through research and design linked to Expo2020 where the pavilion is the beginning of a new way of thinking of sustainable development that values the balance between cultural resilience and international investment. We cannot be fooled by the elite patriarchal discourse that argues that the beauty housed in these images exists outside of development and prevent development and sustainability from being achievable. So clear here is how antithetical visioning has become to the discourse that argues that environmentalists are against development, when in fact, ‘environmentalists’ are asking how we create harmony that will continue to promote equity and peace and appreciate the beauty of our lived-in spaces while allowing us to continue to exist and thrive in these spaces without being affected by industrialised contamination that would undo the natural beauty of all that went before.

The environment is key to the success of the nation; it attracts the people. Conversations over the last few weeks have consolidated ideas about the significance of “Traversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value”and the moment in which it arises. The area that is planned to house the refinery is critical as an ecosystem and also as an archeological site, yet we are happy to plough through and taint the waters.

We must begin to reframe how we see the art, beauty and nature that allows us to appreciate where we live, even for those who only ever see the water once or twice a year because they live in communities cleaved from the coast. We need to understand the disconnect that has been created between the natural image of beauty and its existence as if in splendid counter-distinction from development. The masculinist discourse must be redressed to demonstrate how flawed its representation is and how limited the approach to the immediate will be. The beauty and nature presented in “Traversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value” exist to provide us with life, it is not outside of us or our experiences and should not be understood as something foreign to or in antithesis of sustainable Bahamian development. Without the pristine environment, more than half of our economy will disappear.