By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

The Bahamas, according to the discourse, is a Black country. Majority Rule was established in 1967 and, since then, the language of nationalism has been extremely narrow, exclusive and definitive. Before the power of the majority was inculcated into the halls of Parliament, the language was very different, and usually overlooked the Black population, except as inferior subordinates. However, the face of The Bahamas, while changing, has changed little when seen through messages deployed through art. Yes, art has evolved and developed. The understanding that the Majority are people too, after the end of slavery and the permitting of souls into Black folk was not as earth shattering as one might have expected. The artistic document, though, speaks of differences and similarities of seeing and unseeing that depends little on one’s majority or minority status, but rather on the depth and wealth of one’s artistic practice. Many artists chose to include the more comprehensive and complete vision and voice of The Bahamas. Some chose to ignore or exclude. The nationalist discourse chose to do the latter.

For the last few weeks, this column has focused on the identity as demonstrated, discussed and shown through the exhibition “Medium,” currently on at the NAGB. That show articulates a side of identity and reality that is often elided or erased notwithstanding the shift form minority rule to a majority takeover, which disregards the entire premise of postcolonial empowerment of the folk, as Rex Nettleford might have argued. His folk have been excluded, though spoken for, through electoral representation and majority “empowerment.” In fact, artists who capture the nuanced realities of Over-the-Hill and the interactions between the ‘two worlds,’ are few. The artists who traverse the lines between the splinter groups, of which there are many, that shift and tussle with this either white or Black identity, are few. Though, this is changing as new artists arise, and more seasoned artists see the chinks in the discourse that excludes entire swaths of country and people. The artists who stand firm in the new majority, though loudly unrecognised, are few when compared to the population that chooses to blinker these developments.

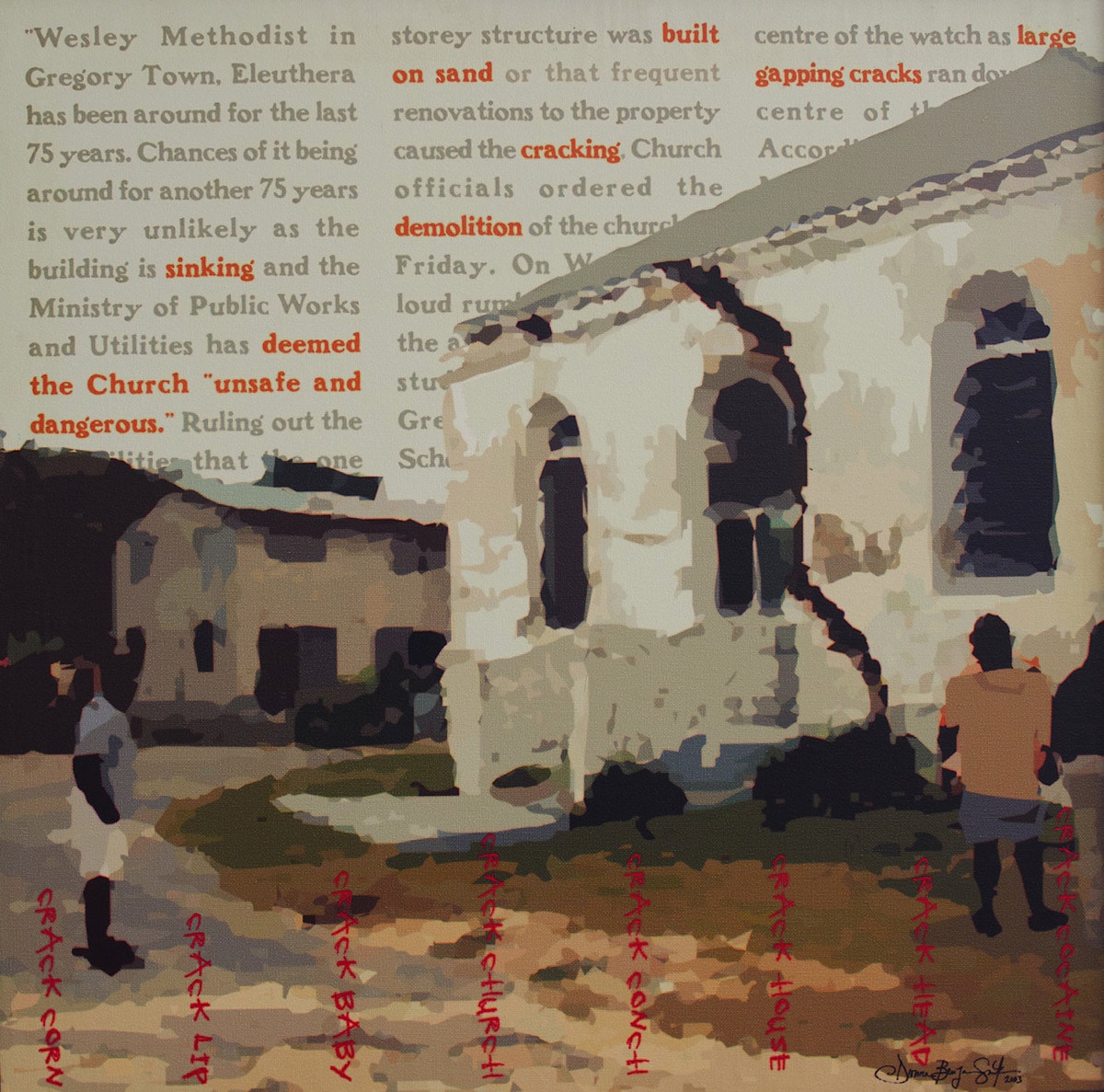

“Built on Sand” (2003), Dionne Benjamin Smith, digital print, 24 x 24. Part of the National Collection (courtesy of the 2003 Collection Fund).

Since Majority Rule, there is an underlying assumption that identity has some how excluded all that was evident before the change. This kind of erasure is powerful; it is as potent as the colonial insistence that nothing was formed in the West Indies without Empire. The need to have voices such as Brent Malone and Alton Lowe is not about token acceptance but about the fullest and complete embracing of Bahamian identity, not small fragments that allow and in fact promote discord. Derek Burrows’ documentary on race and racial identity in Before the trees was strange (date) is a really good start to this conversation. The pain of racism is etched in that screen and the damage this colonising influence does to all in the process is also palpable.

Paul Gilroy is perhaps the best critic to examine when we think about the multi-vocal nature of postcolonial states, which he examines from the perspective of Englishness in his There Ain’t no Black in the Union Jack (1987). Gilroy argues that these are “homogenous national units” such as “a morbid celebration of England and Englishness from which blacks are systematically excluded” (12). By the time we come to Majority Rule, we assume, perhaps wrongly, that post-colonial states where Britain once formed its identity, as Simon Gikandi articulates in Maps of Englishness (1996) and Ian Baucom’s Out of Place that states (199): “Enoch Powell insisted that although a black man may be a British citizen, he can never be an Englishman.” Gikandi, Homi Bhabha, Baucom, Gilroy and many others tackle the overwhelming negative disempowering of Empire through showing how there were always slippages, and that Englishness was usually—if not always—determined, constructed and defined in contradiction to its others. Which is where Benedict Anderson argues that nations are narrated into being through the creation of an identity in literature, art, and news reporting.

Today, the tables are turned and if one is white, Greek, a woman, Persian, Lebanese, one does not belong to this Majority Rule nation. To be sure, we all understand the hard line between Haitians and Bahamians, even if they are as Bahamian as we are because they were born, raised, lived and died here. Indeed, if one is not “black enough” and if one is “too black,” one is also excluded from the space of nationalism and Bahamianness.

Brent Malone’s work, I think, in so many powerful ways, throws this acceptability and spatial and racial determination of identity of belonging into the sharp focus of creation/creativity. He creates work that draws totally on the local. He also creates work that fuses the local with international influences. He and Eddie Minnis are masters of art, or artistic masters, but that also leaves so many other people out of the hard-and-fast, determined majority silenced, once again, by the rulers in majority rule. One of these men is white and the other is black, though of ‘lighter skin,’ he still creates Bahamian work and he is still Bahamian. The narrow enclosure of nationalist Blackness is damaging, as much as that racially poisoned enclosure of whiteness was during colonial days. Malone’s Junkanoo work is as Bahamian as Minnis’s landscapes, yet decidedly and obviously distinct.

When we move to a later generation, we also see the work of Minnis’s daughters Nicole and Roshanne Minnis (now both using different surnames), and theirs is no less Bahamian because they are women, who are a majority though not recognized, and in fact socially marginalized and politically economically and violently excluded. Where did Majority Rule get hijacked by a non-representative group who speaks the language of being the Majority and spawn discord and disassociation?

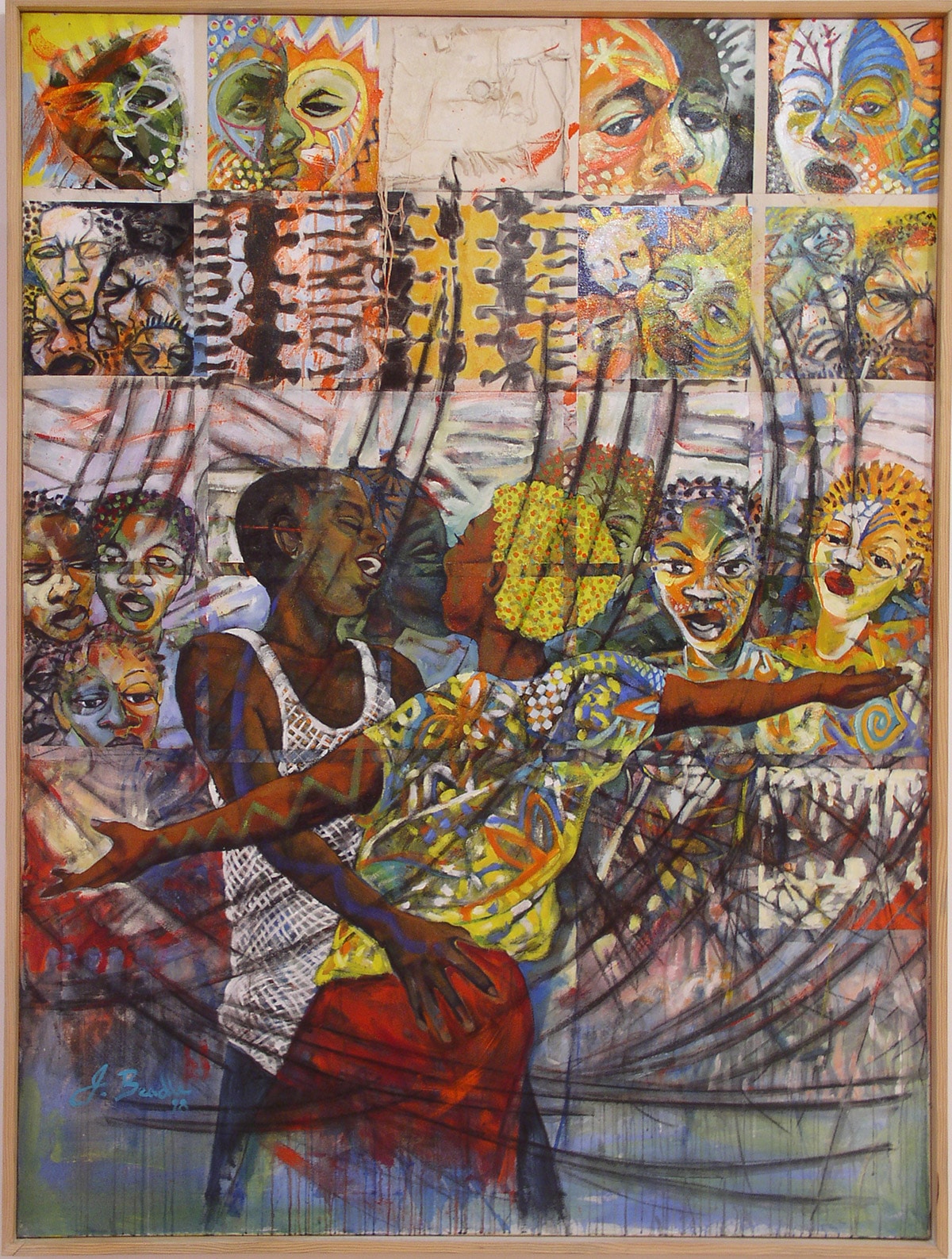

“Emancipation Day Boat Cruise” (2000), John Beadle, acrylic on canvas, 71 x 53. Part of the National collection.

It is insulting to a population that is so mixed and empowered, to be socially excluded, nationally barred from participation in the national space or to claim one’s own identity because there is a group who have determined that they speak for and control the majority. Currently, artists like Lynn and Holly Parotti, Stephen Schmid, Max Taylor, Jeffrey Meris, John Beadle and so many others explore transnationalism and regionalism through their work, but it does not make them any less Bahamian. They are articulating a social and historical reality that is a part of the Bahamian landscape and psyche, but some ignore. However, according to Majority Rule, if we are born here to non-Bahamian parents, we are somehow not Bahamian and, even if we have lived here for the entirety of our lives, we shall be deported forcibly because we do not fit into a national discourse of Bahamianness. As artists and critical thinkers, we must, as Edwidge Danticat states, Create Dangerously. It is when we say that those who are being ignored, erased, excluded from the national debate, from nationality because of their whiteness, brownness, blackness, Greekness, Lebaneseness, Syrianness, Jamaicanness, must be heard, seen, accepted, understood.

The discourse of separation and otherness learned and internalized from an earlier day, when there was no black in the union Jack, is much, too much, alive in this nation space. It was obvious in 2016 with the language used by the Government of the day to refer to the Paradise Island Beach Vendors and Jet Ski operators as national dangers and threats to national stability. The language “others” them in interesting ways for attempting, though breaking the law, to make their voices heard, because no one was listening to them. The Majority was ignoring, the Majority it saw as beneath them and foiling their enrichments plans. The language was around Blackness and working class insecurity. Conversely, during the ‘Dump Protest’ a similar weapon was deployed, but this time it was that the people were too ‘light-skinned’ to belong to the nation. They were not included in Bahamianness. Majority rule discord at work again.

When we consider the work of Dionne Benjamin-Smith and Nadine Seymour-Munroe, we see two different women who are fiercely Bahamian, and who work articulate similar yet different ruminations on what it means to be a Bahamian woman. This is not a definitive or exclusive space, but an open and inclusive dialogue and national expression of creativity and identity.

Powell, above, would not assent to allowing Blacks into Englishness, today, though, Blacks are not allowing Blacks, women, nor whites into Bahamianness, though they sell off every aspect of what they have come to refer to as Bahamian culture. Ironically, it is a culture that silences and erases most of the real culture and traditions of groups of people who reside in an archipelagic nation that disavows the existence of those other islanders and islands unless and until it serves a purpose of national identity caught up in land sale, national refashioning and tourism promotion. When it comes to Bahamianness and identity, though, Majority Rule has become as narrow and exclusive, sexist, misogynist and racialised as Englishness was when used to battle with colonized non-whites over their right to be. In the case of American imperialism in Hawai’i and Cuba, the power of American discourse was used to whiten the space for tourism by deracinating and culturally eradicating groups of people they did not see as being worthy of white republicanism. Christine Skwiot The purposes of paradise: U.S. Tourism and Empire in Cuba and Hawai’i (2010) argues the American republican project went hand in hand with tourism entrenchment and expansion to render exclusive the space and remove any unsightly natives. Even the landscape was changed so that those who were a part of it, were now totally excluded, as Dr. Krista Thompson articulates in her work. As long as we go along with this project, it means removing us from full, participatory citizenship, as it did in Hawai’i.

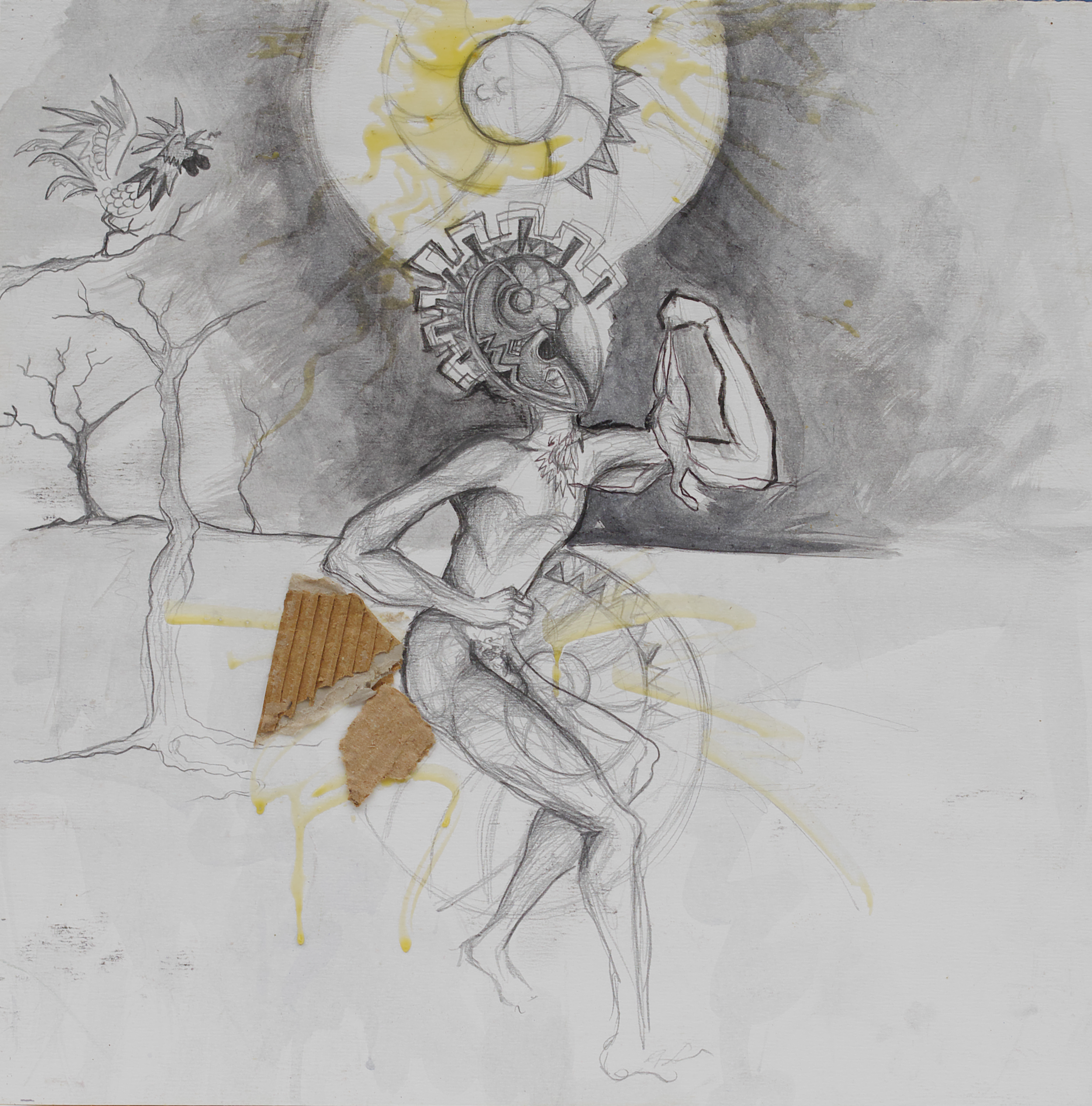

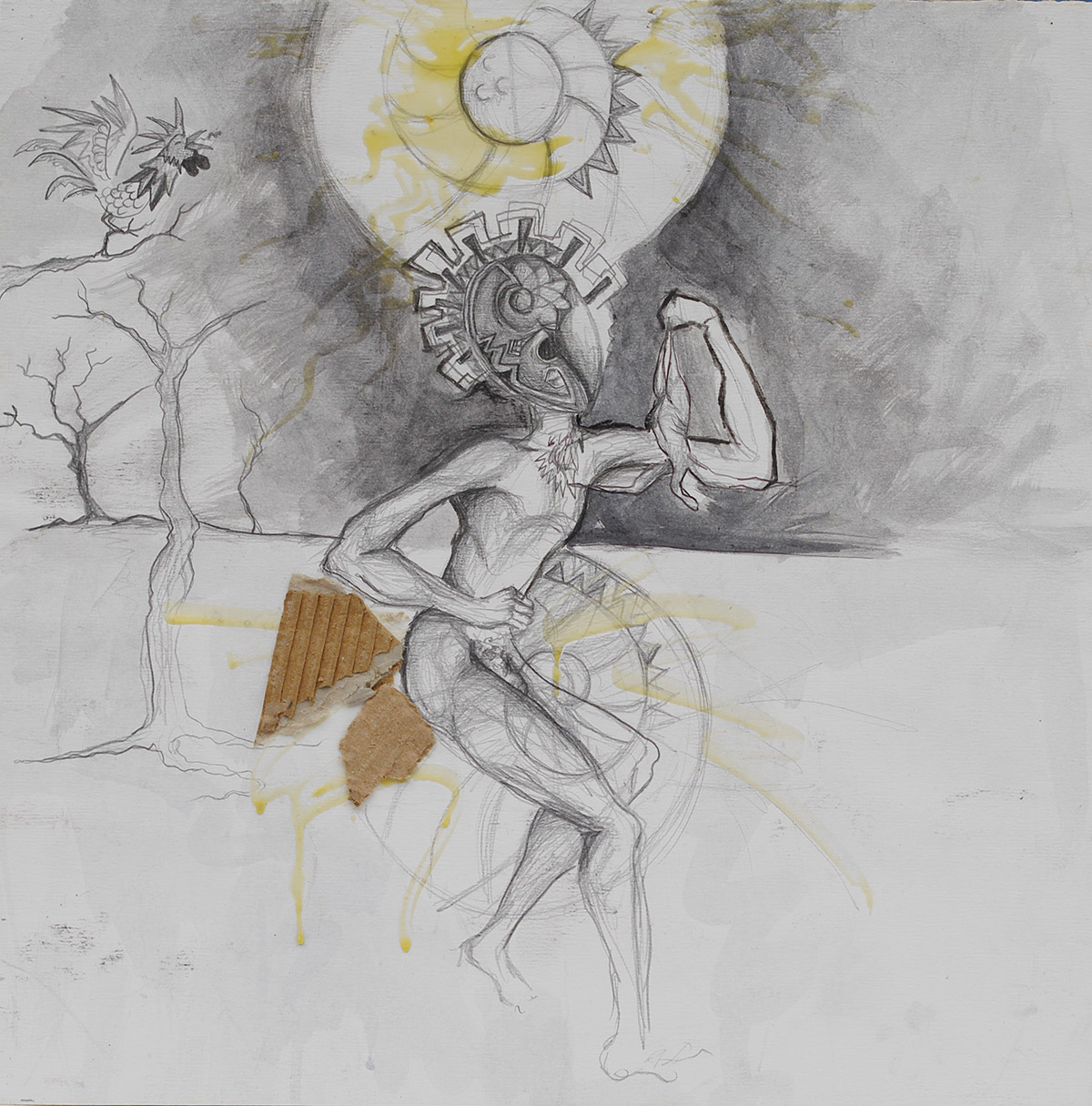

“Things Un-strange” (2010), Jeffrey Meris, mixed media on paper, 19 x 19. Part of the D’Aguilar Art Foundation Collection

“The Waikiki Beach reclamation project opened fourteen hundred acres for development, a broad swath of it for an exclusive recreational and residential enclave. The three-mile Ala Wai Canal built to drain Waikiki and keep it dry reached completion in 1924. Building it destroyed Hawaiian fish ponds, temples, and dwellings, archeological remains of which date back to 1100 C.E., and erased from memory the centuries when Waikiki was shared by ordinary and chiefly Hawaiians, long before ali’i became royals.” (95)

When a people can no longer see themselves in their place of birth, life and death, they have become effectively disarticulated, disavowed, erased deracinated.

The dangerous divide rises more profoundly and the space art cleaves out is essential to articulating a national culture that does not run afoul of speaking for and with a group of people who are allowed to be in every aspect of their identity.