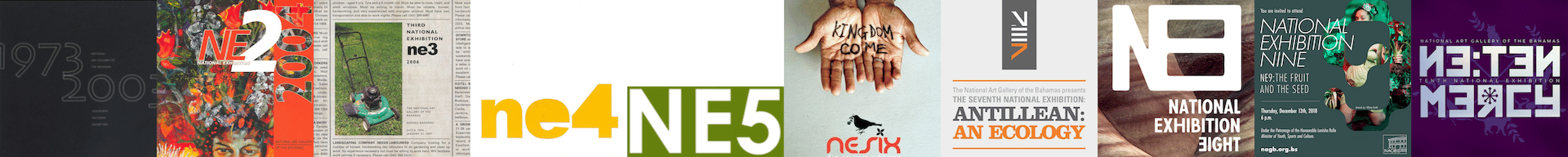

NAGB’s National Exhibition (NE) programming acts as a finger on the pulse of Bahamian art. As our, usually, biennial check-in on the status of creative visual culture in the country, the NE acts as a gauge to see what our creative expression says about us as Bahamians: citizens, diaspora, and residents alike. From the early days of the museum, the first few NE’s challenged what we as a nation believed art in The Bahamas could and should be, despite the occasional bit of furor and pushback given in response to the lack of trope-ical beach scenes many of us were taught to identify our nation with. In these exhibitions, Dr Erica M. James, NAGB’s founding director, and Dr Krista Thompson, both well versed in and passionate about art history, laid the institutional groundwork for critical dialogue in Bahamian contemporary art.

In its execution, the NE is a simple concept: to display artwork by people operating within The Bahamas and its diaspora. But its function is anything but. The NE exists in parallels and contradictions: a snapshot of contemporary Bahamian art, with the view of using it as an archive and gauge for future generations. As our wider history of visual culture gets referenced in current works, the NE exists in the past, the present, and the future as it acts as a time capsule of what Bahamian art looked like at the time. We have moved from the James era of establishing a more inclusive idea of what constitutes Bahamian visual culture, which gave us a foundation to even begin to consider this ourselves, to questioning what aesthetics we identify with in creative production in this country and why. It is from James’ conversation of questioning Bahamian aesthetics and national identity that we are lead to Thompson’s unabashedly contemporary “challenge” to Bahamian audiences. Thompson’s NE3 caused quite the furor with its own questioning of what contemporary art can be in this space and what it means for us to engage with installations and sculptures in our largely wall-based art economy. British curator and former NAGB acting director, David Bailey MBE, made his own mark as the first NE curator to incorporate a theme – something only possible due to the groundwork laid by James and Thompson. Thereby, the NE’s nature is organic as the National Exhibition functions as an organism that lays dormant for two or more years, before emerging from the depths and giving us a mirror to look back at ourselves.

As a nation which prior to 2003 had no art museum, we have certainly covered a lot of ground in a short amount of time. Building on the work of the museum’s first wave of curators and curatorial teams who left their mark on the NE, we have moved into a new moment. John Cox, former NAGB chief curator and curator of the latest NE10: MERCY, first explored the themes of empathy, compassion, and curiosity for the future in the NE6: Kingdom Come. Building on Bailey’s introduction of a theme or prompt for artists to respond to, NE6 was also the first time that the neighbourhood around West Hill Street was truly beginning to be activated, giving the NE a sense of understanding its place and location in a real and tangible way. Taking the theme and running with it, the NE7 gave us our first formally co-curated exhibition with two lead curators: Michael Edwards, a longstanding educator at the University of The Bahamas, and Holly Bynoe. The NE7 Antillean: An Ecology built on both Edwards’ and Bynoe’s work on the postcolonial and how it affects the fabric of Caribbean society and expression. Bynoe would then serve as chief curator for five years, curating the NE8 and NE9 respectively, and through active work of connecting with community, she would draw in our Bahamian diaspora artists into the mix in a meaningful and intentional way. Now we are at the landmark tenth National Exhibition with Cox’s illustrative survey on Bahamian art’s interpretations of what the concept of mercy can mean here, but where do we go from here?

There is a sort of unspoken irony in the idea of a truly “National” Exhibition here, in the sense of the fallacy of a “purely Bahamian” space. We have never been solely and strictly Bahamian (cue the nationalist cries and uproar), but rather representative of the magic that is the mélange of nations and continents distilled in our beautiful and undeniably special Caribbean. But as a community there is a point at which we must learn to be secure within ourselves and what we have to offer and stand tall in our honest and heartfelt creative production enough to let those most like us to enter the fold. Little by little, from its inception to now, the museum has been taking steps to be more inclusive of wider Caribbean and Black Diaspora talent. Though too slowly for some and too soon for others, we all know of the folly in the concept of “perfect timing”. But the main message is this: sometimes we must be willing to “do it scared”, not unlike the careful creative risks and experimental works presented by the artists of the current NE10: MERCY. Producing work as an artist in a country that had to move from the worst hurricane recorded in our history to a global pandemic is no small feat. We recognise those who have managed to maintain a creative practice in these trying times as the shining stars that they are, whether or not if they currently have work on display in the museum’s walls.

If we look at these past ten iterations of the NE as a crucial exercise in nation-building and nurturing a secure sense of Bahamian art identity, then we should consider what the next ten could look like and what their function should be. Looking to the biennial and festival culture of the Caribbean region, as exampled in Kingston Biennial, Ghetto Biennale, Trinidad and Tobago Film Festival, and TransOceanic Visual Exchange, and seeing home-grown art events that make themselves inclusive to artists from the region and diaspora, the question then must be raised: when can we in The Bahamas stand tall and proudly in our National Exhibitions and feel secure in welcoming in our wider Caribbean family? It isn’t a matter of how or why, but specifically when. The growth of these important vital signs and check-ins on creative culture is inevitable – by their nature, to survive they must expand and open the conversation as the art world at large demands. But when will we shake off our insecurity or distrust enough to give it an honest try? In an ever-shifting, ever-growing international community under globalization – made even more palpable with the post-pandemic paradigm shift of remote working – our ideas of boundaries and spaces are either collapsing, or evolving to suit the needs of the digital contemporary.

When it took five continents to make up this rich region that we are fortunate enough to have our roots in, climate crisis and postcolonial traumas aside, why shouldn’t we want to see how carefully our neighbours have tended to their creative gardens too? If there’s one thing that uprisings and rebellions in this region have taught us, it’s that we make true progress and change happen when we do it together.