The NAGB’s National Exhibition (NE) programming acts as a finger on the pulse of Bahamian art. As our, usually, biennial check-in on the status of creative visual culture in the country, the NE acts a gauge to see what our creative expression says about us as Bahamians: citizens, diaspora, and residents alike. After reaching our landmark 10th National Exhibition, NE10: “MERCY”, we must ask the question: how do we grow from here?

Currently browsing: Stories

Peggy Hering’s “Lilies” (1984): On Being Both Student and Teacher

By Natalie Willis

The Caribbean is in many ways a place of and for the nomadic. There is an irony then in the way that American artist Peggy Hering found herself referencing Claude Monet’s water lilies with her own “Lilies” (1984), which were painted at his home for the last 30 years of his practice. The jarring difference between those seemingly shifting, moving art makers, and those who stand stock-still devoting time to the exact opposite which is the enduring, is all presented to be considered in Hering’s dreamy landscape. Some may be familiar with her work gifted to us from the FINCO commissions of scenes Over-the-Hill, but Hering and her work are a little elusive for those of us who weren’t around in Nassau in the 70s and 80s when Hering lived here. This gem in the Dawn Davies Collection is a good departure point for probing into the life of this expatriate artist.

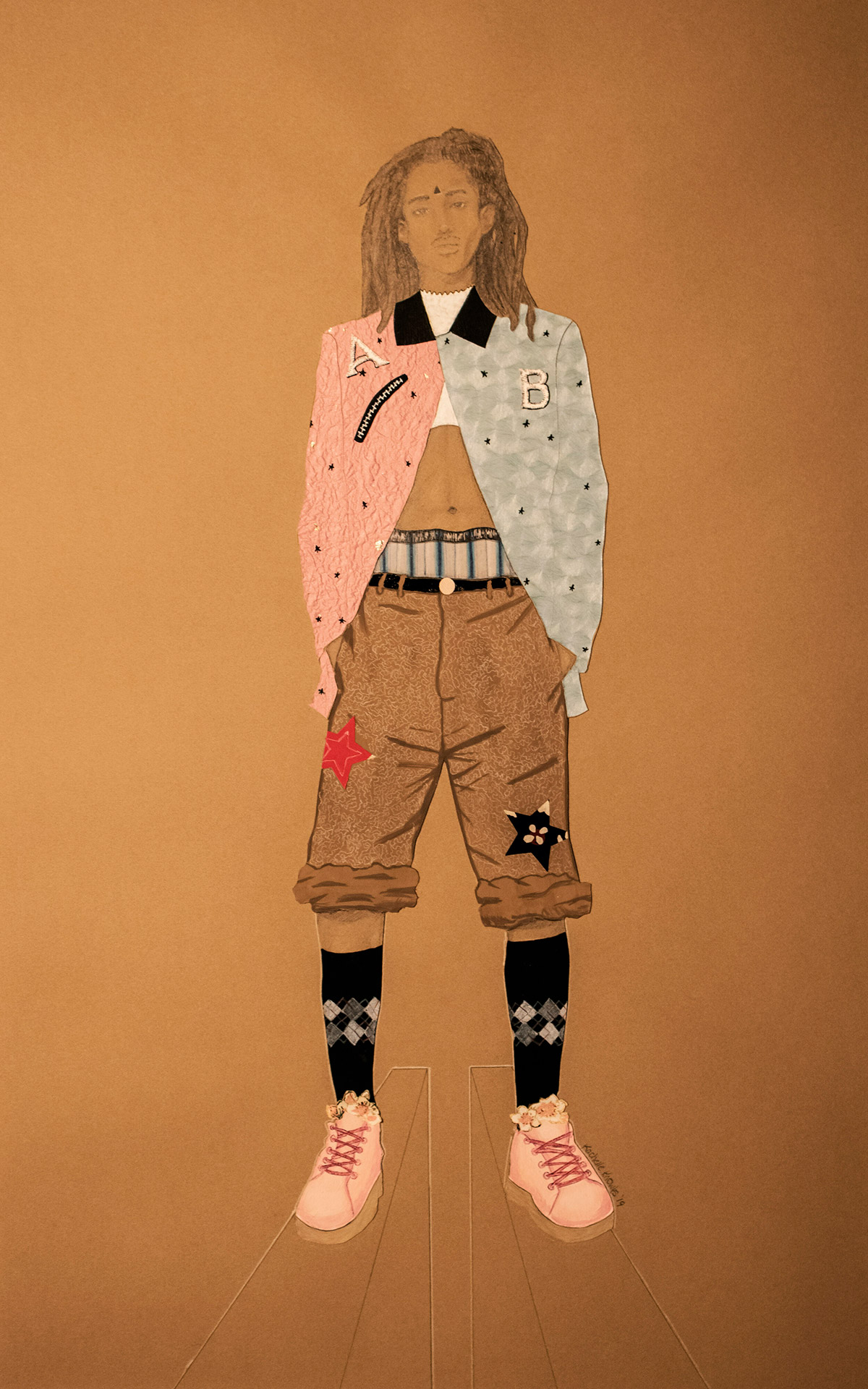

Adaptability & Draughts(woman)ship: Kachelle Knowles Builds a Practice of Representation That Takes Action

By Natalie Willis. We are not used to seeing ourselves outside of the lens of tourism as Bahamians. This is troublesome for a newly-independent nation not yet 50 years old, and with 200 years of tourism weighing in above our heads. The decolonial work of imaging ourselves as Bahamians (particularly as Black Bahamians) is slow-going but gaining more visibility. The representation for many of our Black non-Bahamian people of this nation is in a more dire state. These observations and lines of questioning are brought to the forefront in Kachelle Knowles’ delicate and tenderly draughted portraits of the Black Bahamian man in her body of work for “Bahamian Man Since Time,” which recently closed in the NAGB’s Project Space. In the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian and its painful shifts and turns – and in the museum’s efforts to respond appropriately to hurricane efforts, we wanted to share some words on the exhibition as it became the site of a donation centre for Equality Bahamas and Lend-A-Hand Bahamas. These works were the backdrop to so many of your efforts to assist and to be supported.

“Wellington Street Dwelling”: Exploring the Bahamian Vernacular

By Kelly Fowler, Guest Writer. An island landscape in the mind of a non-native may include picturesque coastal scenes of blue and turquoise shaded waters gradually transitioning to crystalline, onto shallow shores of powder white sandy beach, and further to lush foliage of coconut and palm trees. To the native Bahamian, the island landscape may vary considerably. The landscape may range anywhere from the quintessential narrow, yet neat streets featuring well-kept, board houses nestled among vibrant Bougainvillea, Poinciana and golden shower trees, to scenes of markets, daily life and the historic Over-the-Hill community where centuries-old silk cotton grow, fruit trees flourish and royal Bahamian potcakes roam freely. Both the outsider’s notion and the insider’s experience are represented in Bahamian art. Melissa Maura’s 1983 oil on canvas painting entitled Wellington Street Dwelling is a glimpse into an insider’s experience of island life and landscape. The painting draws the viewer into the lived experience of the native Bahamian and invites the onlooker to reflect on the diversity of the island landscape and how the landscape has changed over time.

Chan Pratt’s Work Speaks to the Urbanization of the Bahamian Landscape

By Blake Fox. Slated to open on Thursday, May 2nd, 2019 at The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB), “Resurrection” is a retrospective of over 100 paintings by noteworthy Bahamian artist Chan Pratt. The collection prominently features Bahamian landscapes between the 1980s and ‘90s with scrupulous attention to the local flora. Having died suddenly–and at a young age–much of Pratt’s work was undocumented and there is an unfortunate lack of historical information on the artist and his practice. To resolve this lack of exposure, the NAGB is working with Dewitt Chan (DC) Pratt, Chan Pratt’s son, and over 20 collectors of Pratt’s work to pay homage to his talent which was sometimes overlooked.

The Black Woman Body Paradox

Feature The Black Woman Body Paradox Natalie Willis ● April 10, 2019 There are certain things that should unsettle us,

The Weight of the Tide: Lynn Parotti’s “Time Under Tension” in Review

By Letitia M. Pratt,The D’Aguilar Art Foundation . Lynn Parotti’s Time Under Tension was a compact exhibition that communicated a profound message in its simplicity. All of the work shown was a homage to The Bahamas’ aquatic environment, which – according to ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies – is suffering major damage because of coral bleaching, a direct result of global warming. Nestled carefully in The D’Aguilar Art Foundation’s (DAF) intimate gallery space, Parotti’s new series of works, “Bahama Land” is a vibrant epitaph to the beauty of the Bahamian coral. Her seascapes are illustrated from the point of view of somebody who is just above the water looking down (perhaps over the hull of a boat), or right above the ocean floor. When confronted with the vibrancy and electric colours of these spaces, which are depicted with such indulgent, viscous applications of oil paint, the works speak like relics of the past.

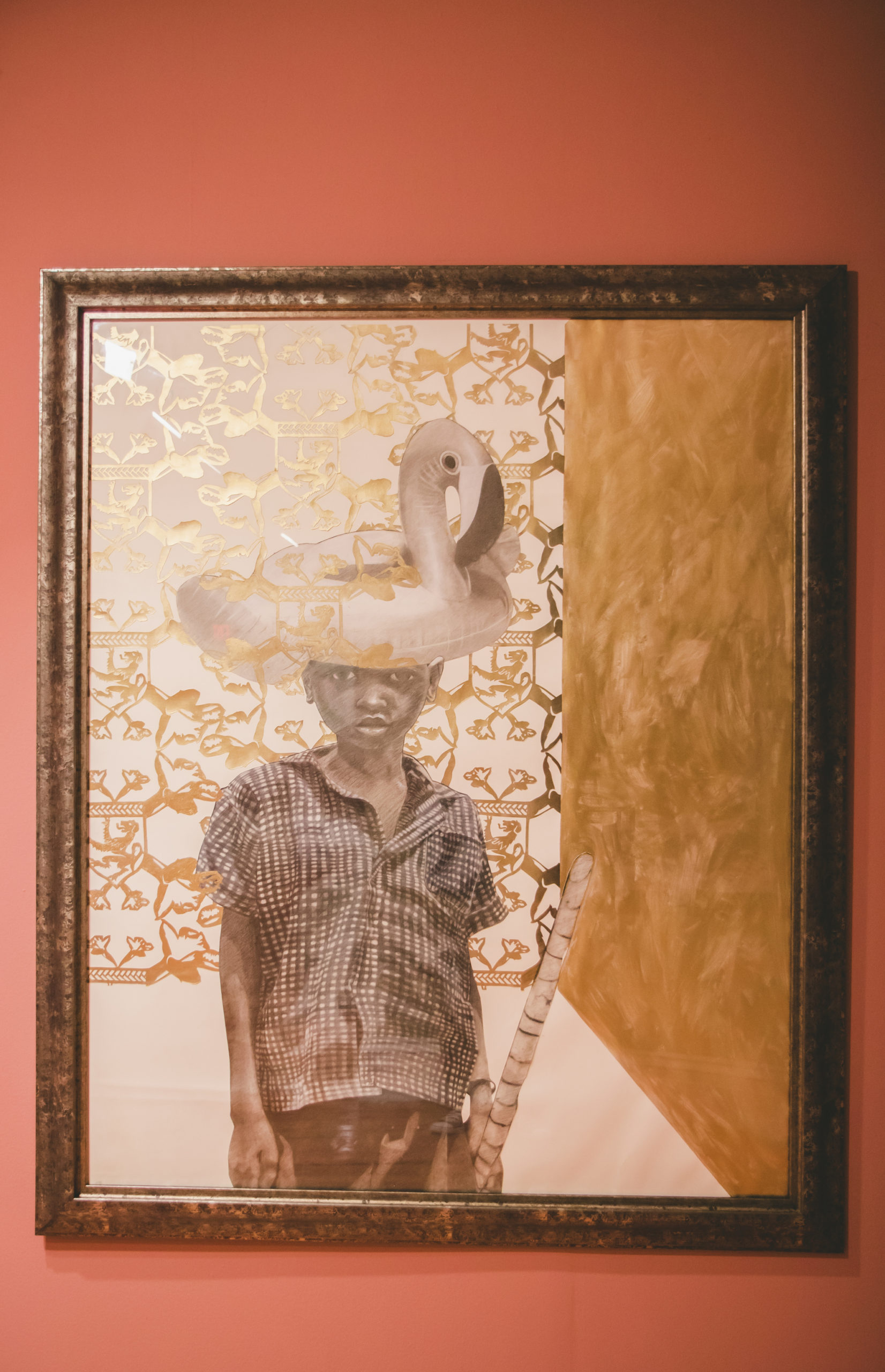

The Island Repeated: Toni Alexia Roach’s Patterned Approach to Confronting the Past

By Natalie Willis. The land we live in feels like a repetition. We are a repetition of limestone rocks across shallow seas. We are repetitions of faces across families. We repeat the things we learn in school and church and wherever else – many times without critique, and, most disconcertingly, we repeat the same models of power–mainly paternalistic–from hundreds of years ago. This is at the heart of what Toni Alexia Roach gets to in her work for the “NE9: The Fruit and The Seed.” We look at the visual repetitions – palm tree after palm tree, and beach after beach – but we also see that these images are not symbolic of the place we live in, of the Caribbean, they are symbolic of the very idea of the Caribbean picturesque.

A Botanical of Grief: Yasmin Glinton and Charlotte Henay Connect with Ancestors’ Voices and Put Mother Tongue to Poetry

By Natalie Willis. In much of cultural studies, the Caribbean region has been discussed as a place where people feel an uneasy, tense tie to landscape due to our history of people being displaced here. Paradise or purgatory, whether these islands were viewed as restorative or a place of exile – and truthfully, we have had both stories ring true throughout time, it’s all in the branding. Tourist narratives aside, this space is a difficult one to feel truly close to, the landscape feels at once that it is ours and that it is without of our reach given the fact we are all “from elsewhere”, as Stuart Hall (the late Jamaican scholar and father of cultural studies) stated. Poetry in visual art can also be a difficult fit – is it language? Is it visual? Is it both? Problematising our ties to the land and the neat boxes that traditionalists might wish to shove the vast world of poetry into, are the unapologetic works of Yasmin Glinton and Charlotte Henay. “A Botanical of Grief” (2018), displayed in subtle silver script bearing powerful words of great weight, exists between – like so many of us in the Caribbean. The work is between voices: of the authors, of their ancestors, of poet and of artist, but it also exists in a liminal space physically as it spans the high walls of the stairwell of the 1860’s old bones that make up the Villa Doyle. Stairs are between places, and so are we as children of the Caribbean. We are between Africa and Europe, between India and China, we come from Arawaks, Tainos and Caribs with difficult access to those mother tongues – and most importantly, we are an amalgam of any and all combinations of these continents.

Under Attack: Averia Wright’s Elevating the Blue Light Special and the Dualities of Bahamian Identity

By Ethan Knowles. War for much of the Caribbean is a remote idea – a thing of books, films and faraway lands. In a region characterized by calm waters, light breezes and laidback locals, the notion seems oddly out of place. But the idea is not just a distant one. It’s also awfully dangerous. War necessarily conflicts with what Caribbean nations like The Bahamas ‘should’ be, that is, a peaceful escape for the worn and overworked. Put simply: conflict in the Caribbean is off-brand. And in our Bahamaland, where at least sixty percent of the GDP and half the workforce rely on a carefully manufactured and embellished brand image, being off-brand can be about as deadly as armed conflict. As the daughter of a straw vendor in a family of straw vendors, Bahamian sculptor and expanded practice artist Averia Wright is well-acquainted with the brand of paradise we manufacture here. Her work, which grapples with issues affecting both The Bahamas and the region at large, is particularly concerned with tourism and its role as a neocolonialist system in the country today. Elevating the Blue Light Special (2018), Wright’s submission for the “NE9: The Fruit and The Seed,” addresses just this concern, exposing and critiquing the commercialisation of identity which is so central to the contemporary tourist economy.