By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

Migration, the moving image, the environment and cultural identity are all a part of the treasure chest of what could be referred to as national or cultural identity. In the context of The Bahamas, cultural identity is distinct and unique because of the archipelagic nature of the country. This, of course, takes into consideration all the nuances and complexities of the differences between–let’s say Bimini and Ragged Island–that have very little in common, but all form a part of what makes up Bahamian national identity.

The Bahamas, in many ways, is defined by the sea, even though many of our communities live with their backs to the sea. The sea is History, according to Derek Walcott, and the sea is life. Much of the experiences are brought together by the sea and its medium for exchange and destruction. At this historical and cultural juncture, the sea holds our bones, it keeps our memories, and it holds our suffering as it washes on every Caribbean shore. The sea contains those souls brought over from the African Continent in the bowels of ships, tortured and chained, transported into a new reality, those who died on board and those who jumped to their death, all of these stories or narratives are held in the sea.

Still from “Cargo,” with feature film veteran Gessica Geneus (left) and newcomer Brian Diligence (right)

It is significant to adopt Edouard Glissant’s use of submerged memory as necessary to grappling with how the sea, in fact, connects us. Cultural identity is linked to the sea as we continue to redefine who we are because who we are is always changing, as much as the sands shift and land masses change with the erosion and impact of climate change, of raging waters slamming into sandy shores, we too are changed by time.

In this year’s Travelling Caribbean Film Showcase, the Bahamian film “In My Father’s Land” by Tyler Johnson was one of the featured documentaries. The film follows a Haitian who has been resident in The Bahamas for over forty years, and who lives precariously given his relationship to immigration. The film relies heavily on water. Water washes all the shores of the islands in question, and it similarly defines a relationship with migration that is at once painful and divisive. An interview conducted with a migrant who has lived in the Dominican Republic for years reveals the depth of feelings of dehumanisation and overwhelming sadness. Meantime, in The Bahamas, countless young people are being told that they do not belong. They are stateless living in a state of transition from nowhere to everywhere and stuck in limbo. They do not belong to the nation they inhabit, yet they also do not belong to the nation they are told they should claim. This documentary contains an important part of the Bahamian story which resonates with Kareem Mortimer’s “Cargo.”

Slavery and post-emancipation labour exploitation are a permanent marker of Caribbean history and cultural identities or realities, often the latter is controlled by forces external to our shores, but these forces define and refine who we are and how we see ourselves and others who look like us. They can either divide or unite; often they choose to separate because in division they gain power and strength. In the division between being Haitian and Dominican, large multi or transnational sugar corporations gain influence because they can employ Black bodies for peanuts, building on a history of disharmony, sown by colonial legacies of exploitation, power and control.

The Sugar Babies (Amy Serrano, 2007), The Price of Sugar (Bill Haney, 2007), The Price of Memory (Karen Marks Mafundikwa, 2014) are three documentaries that draw a line under this exploitation and enforced suffering to maintain the bottom line. These three documentaries, two of which have been presented this year in film festival speak to continued international patterns of neocolonialism that speak to the realities. These all speak to the making of division and the benefiting of large foreign corporations through inflicting policies, creating petit oligarchs in local economies and deepening massive inequalities that drive up violence in Banana Republics. We see not these overlapping images, we do not look at the similarities between Haiti, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic and The Bahamas, in part because we believe those leaders who say that we are exceptional and that if we identify culturally with those less than stellar examples of nationalism and development, we will become like them. Tragically, we are becoming like them as patterns of influence, and our insistence on division based on fictionalised boundaries of nationalism abound.

As we speak of moving forward into the 21st century, we also see language that continues to demonstrate our understanding that there are humans who are inherently inferior and so deserve to enjoy fewer rights than others. This belief is saved especially for those born to Haitian parents in The Bahamas, notwithstanding their claim to citizenship evidenced by the Constitution that gives them the right to apply between 18-19 and to be granted upon application. Our inability to understand the difference between those who are born here and those who come here seems ironically flawed and willfully blind. Meanwhile, the sea connects us with all of the parts of life, of a history of geography we do not wish to see.

Cultural identity

Stuart Hall discusses the concept of cultural identity, where our cultural identities are not ahistorical. They are not resistant to the changes that come with time, place and history (Cultural Identity and Cinematic Representation, 70). Cultural identity, therefore, “is not a fixed origin to which we can make some final and absolute Return” (ibid 72).

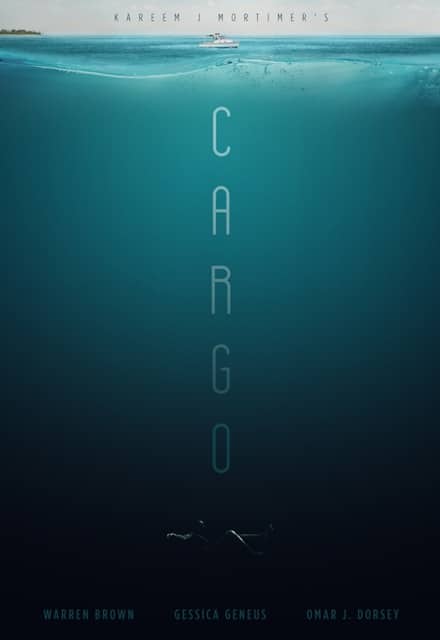

Film poster for “Cargo,” concept conceived by Best Ever Films, executed by Daniel Spatzek.

In the Travelling Caribbean Film Showcase being held at the University of The Bahamas this week, perhaps one of the better encapsulations of the constant intransitiveness of many Caribbean people is the documentary by UK/Trinidadian filmmaker “Dreams in Transition” by Karin Martinez. This is an excellent and thought-provoking exploration of identity and home. Identity, as Stuart Hall says, is always in transition it is being and becoming. It is significant when we look at identity as an enunciation of self, but also an assemblage of aspects of cultural identity. Her documentary of identity and shared parts not separated by migration, never cleaved, should resonate with the identities that allow us to draw stark lines between us in the Northern Bahamas and us in the Southern Islands, though we are a nation.

The travesty of cultural and national identity is that it is always a narration, to use the words of Benedict Anderson, “nation is a narration.” This draws too on Hayden White’s concept of History being a narrative, yet colonial history silences these histories. The other complexity of national identity formation is its exclusive zones, created heavily bordered and reactionary that form arid regions of non-belonging and division that justify and increase violence. These regions are saved for, but not confined to anyone too Black to fit into the national paradigm of Blackness and too white to match into the widespread understanding of Bahamianness.

Johnson’s documentary builds on this identity and the polemics around it by speaking with and allowing them to speak for themselves though Bahamians may choose not to hear them. It is ironic that the construction of Bahamianness can be so anti-Black while being anti-white. Johnson brings together his nuanced reading with Mortimer’s oxymoronic and disconsolate disjuncture of reading under, over, through Bahamian identity created through normalising artificial separation based on colour and class and buttressed by distance and misconceived differences and divergences that have allowed the power dynamics and division to continue.

The narration that we do not belong to the Caribbean has been flogged to death, yet we are as Caribbean as our neighbours. We are in a sea of connectivity. The sea is life, as is so clearly shown in Johnson’s “In My Father’s Land”, and yet it is also death as seen so clearly in Mortimer’s “Cargo”.

However, as Anina Major attests, we are a fragile body yet a resilient people, we must now hear the true stories of nationalism and division for what they are. When we see images, moving or still, artwork, installations and the day to day of life filled with hardships and discordance, but complete with moments of deep feeling and connectivity we are reminded of our humanity. Art in all its complexities brings us back to our humanity, our discordant belonging and our soulfulness. Identity can never be fixed, mainly when its fixed rigidity benefits those in power and those they enact policies on behalf of, not those they are meant to serve.