Dr Ian Bethell Bennett

Sorry, Not Sorry a short experimental film by Alberta Whittle juxtaposes tourism and post-enslavement-dispossession in the British Caribbean. An intriguing mise-en-scène combined with sharp overlaying and interweaving text, image, audio and nuance that brings all sorts of feelings to the fore, from contradictions to harmonies. The harmony in the background, though clashes with the discordant foreground that allows the moving image the salience it has to document, to articulate, to illustrate the unbecoming side of colonialism and independence. Again, the irony of postcolonial independence is that there is no real sovereignty as governments are only held in power by foreign direct investors who own the economy, by owning resorts where the Bacardi-sipping-frolicking-lithe bodies stay during their fantasy time in paradise.

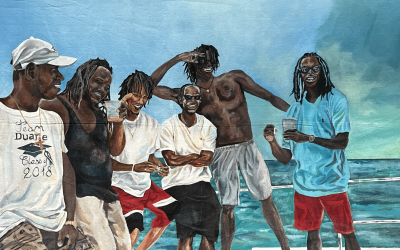

Still from “Sorry, not sorry”, Alberta Whittle, 2018, HD Video, 6 mins.

Sorry, not sorry, is coupled with seminal film Handsworth Songs, which is a painful yet revelatory documentary of British civility and colonial ‘savagery’ or incivility. This is a theme that resounds throughout E.M Forster’s A Passage To India (1924) and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), later re-penned by (but really reconstructed from before the story unfolded) by Jean Rhys in Wide Sargasso Sea (1966). So much can be said about the un-civilising of the savage as seen, but when the other story is told, as Rhys does, we see context.

The first of four programmes of the newly launched film series, “One Turn of the Revolution”–in partnership with LUX Scotland and the British Council–coincides with the artistic response to slavery in the We Suffer to Remain exhibition, which articulates in the very title the hardship and long enduring suffering, exploitation, sexploitation and defacement West Indians ‘suffer’ through as they insist on their humanity in the face of ongoing erasure and disavowing of responsibility for slavery.

Ironies are deep and profound as slavery, always touted as a gentle reality in The Bahamas and almost not discussed in Britain except that so much of the economy and wealth of Britain derives from slavery and indenture. An anthology of 100 Years of the abolition of Indenture edited by David Dabydeen has just recently been published while ongoing, is the study and work being done on slavery and abolition “Legacies of British Slave-ownership” at University College London, which explores all those rich and power families, their links and linkages and their wealth garnered on the backs of negroes enslaved in the transatlantic slave trade and resident in the West indies.

Much research and writing has gone on around these themes and is coupled with research on the East India Company 1757-1857 which explores, in part, the linkages between home and East India Company which was also displayed in Trappings of Trade Display at Osterley Park and House. The last ten years has witnessed much interest in these themes, a great deal of it, however, has been a nostalgia for a return to the past, the simple past, of empire and belonging. Or a past where people ‘knew’ their places. On the Caribbean side, a study edited by Madge and Andrew Hann Slavery and the British Country House provides an excellent and beautiful tool for re-reading slavery’s influence on/over Britain. These projects seem to remove the political bite from the atrocities of ‘ancient’ history, though much of recent history continues to play out these and similar atrocities. These moments are salient readings of how and where the Caribbean fits into the British Empire, and the post-imperial commonwealth.

We are greatly indebted to LUX Scotland, the British Council and the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas for bringing this wave of confluence to our screen. The films screened on Thursday 17th May, deal expressly with the legacies of enslavement and British incursion into the Caribbean that results in the later movement of naturalized or indigenized Caribbean people, British citizens at that time or subjects under the Nationality Act of 1948 to Britain to serve the mother country/empire. These people suffered awful racism and discrimination, as can be clearly and almost palpably witnessed in these films, throughout their lives in Britain.

Watch Whittle’s film here: https://vimeo.com/265731769

The artistic frame allows the bitter sting of empire and racism to remain intact without raising hackles in a deeply polarized and conservative present day world and discourse that has redeployed projects of alienation and erasure. This was experienced firsthand with censoring the hard conversations.

Documentary film often, especially when combined with experimental film, allows a certain levity within the toxicity of a horrible story, history, herstory usually erased by imperial/colonial mechanisms to silence and oppress the other-versions of exploitation and marginalisation. Film, much like music, is less hard to communicate through as there is less burden on the viewer to ‘read’ text or to understand language usually foreign to today’s limited readership. The soundscapes and visualscapes of both films provide much food for thought as well as deeply nuanced silences and makes audible voices and retellings that were often overlooked, undervalued or totally ignored.

Handsworth Songs (1986), captures this along with the horrible reality of the Handsworth riots that have scarred Britain and, and more so, those who suffered to remain. As a child, I would have felt some of this resentment against Caribbean folk in England, though few cared to know that their time in the tropics had paved the way to this ‘colonisation in reverse’ Miss Lou’s words. The sour after effect left in so many mouths remains, decades later. The film begins with two disconnected images and songs that seem to belie normalcy. The second image is reminiscent of Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), followed almost immediately by the sound of a siren and then people shouting and then more birds. The narratives are compelling and powerful. Yet the resonance is deeper than one would expect. It brings up painful records, often consistent with music’s ability to thrust us back into the past, where we were and what we were doing when we heard a particular song or smell a particular scent. Memories flood back and we are rendered almost unreasonable by the impact of emotion.

As the waves wash up against the shore in Sorry, not sorry (2018), the song strikes up, a melody of a light Caribbean instrumental that flows into “be what you want to be, taking things the way they come, nothing is as nice as finding paradise and sipping on Bacardi rum” captures light skinned and white revelers in the surf and doing the paradise thing, juxtaposed by cane-cutting negroes, at hard labour in the fields. The bitter irony is clear, as are the paradoxes. Yet, paradise is never for those who inhabit it.

Still from “Sorry, not sorry”, Alberta Whittle, 2018, HD Video, 6 mins.

The Windrush generation becomes the sugar in the bottom of a cup of tea as British Labour Party politician–Member of Parliament for Tottenham–David Lammy states: “I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea”. Whittle’s experimental film, similar to the documentary, articulates the bitter savage promises broken of coming to the mother country. In fact, as Windrush Brits are rounded up, deported and/or rendered illegal in their own country, the British government encourages a sharp and forked dialogue around dispossessing them and condoning far-right activists’ racist and racialised discrimination, we see that little has changed except for the stiff upper lip with which it is delivered. The absolute travesty of this particular historical moment and the documentaries when ‘read’ in concert with works of art from across history and enjoyed with a glass of rum and a song of resistance, tells the story of history revisited.

How did we get here, again?