By Kevanté A.C. Cash

NAGB Correspondent

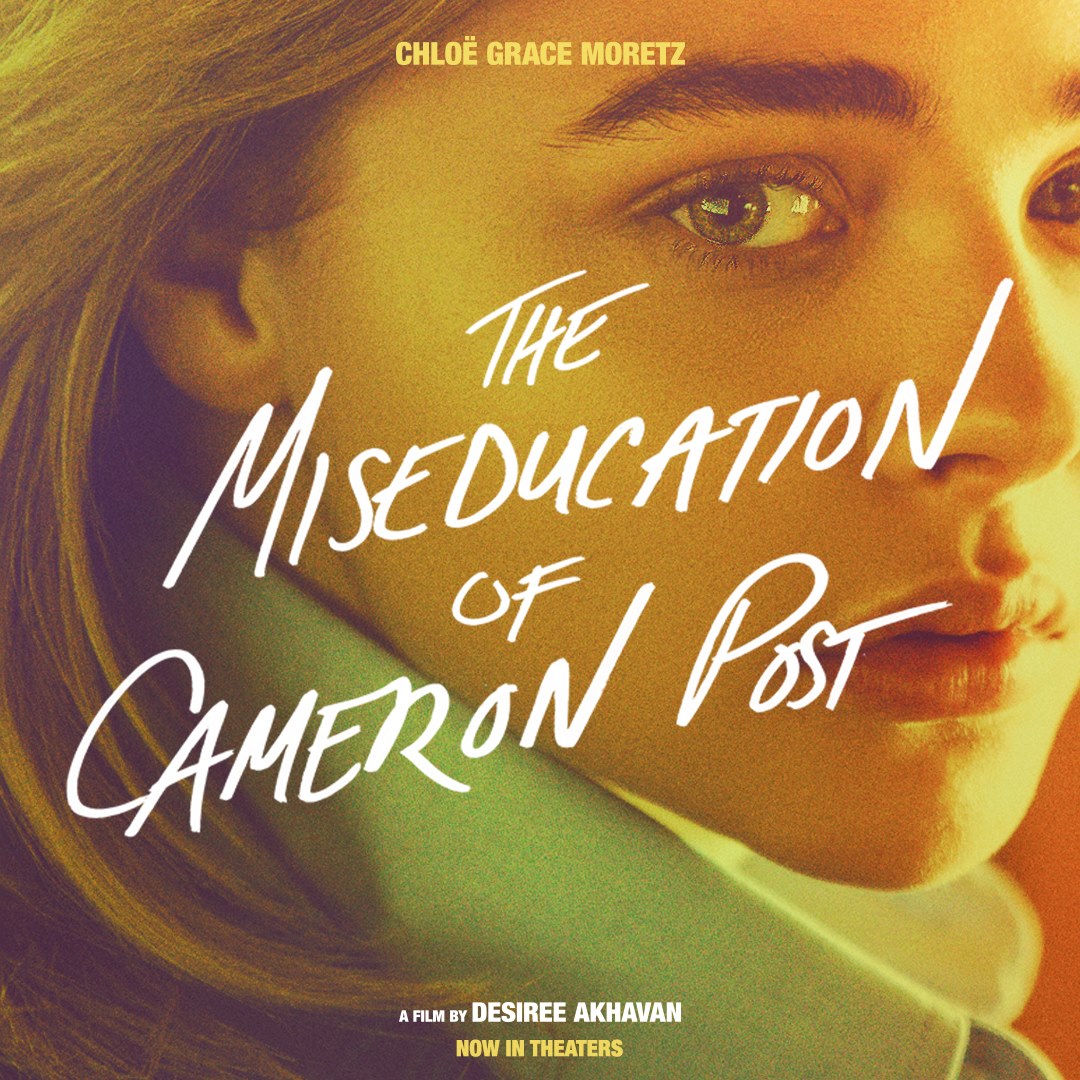

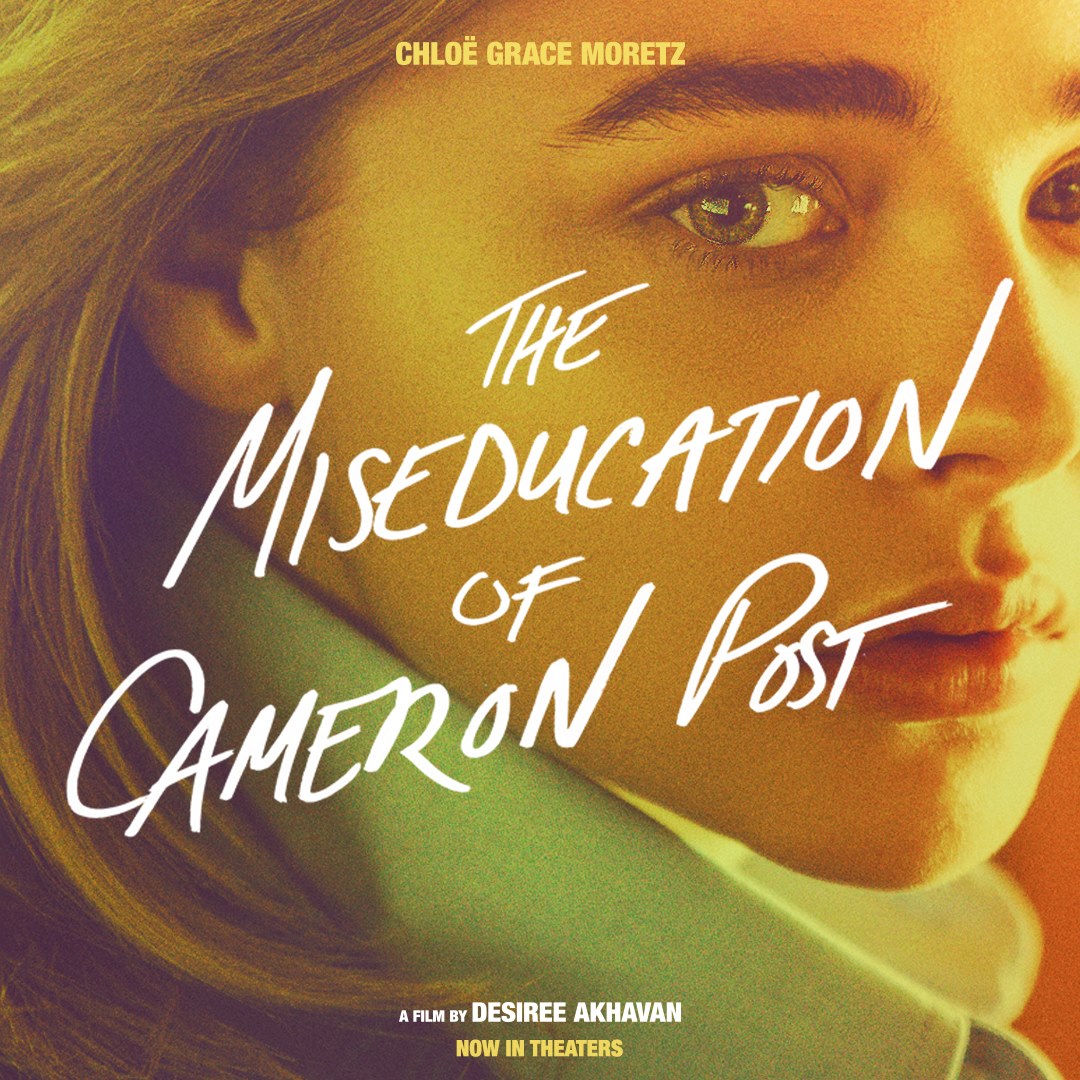

The storyline of the film The Miseducation of Cameron Post (2018)—the Grand Jury Prize Winner at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival—is one not too far-fetched to imagine for a queer person living in the Caribbean today, especially when considering the theme of malicious religious manipulation coming to the fore throughout the film.

Given the recent polarizing conversations via social media and other channels among Bahamian LGBT rights activist Erin Greene and Jamaican singer-songwriter Buju Banton, whose 1992 hit Boom Bye Bye inspired controversy among the Bahamian people just last month, the timing of this film’s showing at the third annual Island House Film Festival (TIHFF) seems rather fitting and almost intentional, as a move towards a step in a much progressive direction.

Based on a book written by Emily Danforth and set in the U.S. in the early 1990s, closeted lesbian teenager Cameron Post is faced with “the consequences of her actions” when she is caught in the backseat of a car having sex with another teenage girl by her boyfriend. Distraught, he leaves in tears and works up the nerve to tell Cameron’s guardians – her very Christian aunt and uncle – about the occurrence. Not in the slightest way pleased to hear of the news, Aunt Ruth packs up her belongings and ships her off to a treatment centre where she is subjected to questionable gay conversion therapies, in hopes she would “get better” soon or be rid of the gay demon.

Immediately, one is cognizant of how powerful the symbol of a parental figure plays within a child’s life; that no matter how wrong or misguided the individual may be, they should and will always have the last say – an attribute that surely is prevalent among our collective conservative Caribbean culture.

Upon Cameron’s arrival at the centre, she makes a connection with a girl ‘disciple’ (the term used to describe new converts), and they become friends. After being forced to sign the membership agreement with the facility, Cameron begins her journey of therapy and treatment.

There are parts of the film that makes for somewhat uneasy viewing, and one is left to question the legitimacy of a centre like this. One scene takes place in a field where the disciples are asked to pair up, lie on the grass and reflect on the times they experienced ‘SSA’ (same-sex attraction). Indifferent, Cameron avoids the exercise altogether with her partner and winds up being called out for it. She is then forced to talk about the girl she fell in love with back home in front of the entire class. Any introverted individual can imagine the discomfort and horror Cameron had to endure while being coerced to perform an activity of such nature. After sharing, Cameron is told by the class facilitator that her feelings of romance for her friend are mistaken with platonic feelings of admiration – that the things she admires about her friend are merely the things she admires within herself, and her friend is just the reflection of that.

This form of manipulation, crafty yet dangerous, is recognisable among a culture of religiosity where anything outside of a heteronormative gaze and way of living is not acceptable, and anything, at all costs, must be done to correct this “contrariness”. Victims of homophobia are steadily abused and manipulated on repeat until they are left to feel hopeless and without a reason to live just like Mark, a character in the film, who ends up self-injuring after being denied his father’s permission to return home because his mannerisms still seemed “too feminine.”

After Cameron realises what happens to Mark, she becomes infuriated. She is through pretending to go along with the process to make a way out for herself. She demands answers about Mark and his conditioning and treatment, but when no one can give a logical explanation as to why the facilitators of the centre are “programming people to hate themselves,” she and her newly found friends create an escape to flee the facility and promise never to look back again.

A timeless plot among generations of queer teens about learning to love and accept one’s self through situations of adversity, The Miseducation of Cameron Post was a perfect selection for inclusion to display among films within the TIHFF this past weekend. It calls a level of openness to sit and engage with a perspective outside of one’s own, question the state of The Bahamas today and reflect on how religious principles and values misused and misinterpreted have aided in the reinforcement of homophobia across the Caribbean region. The Miseducation of Cameron Post is recommended for all to see.