By Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett

The University of The Bahamas

The current show at The Current Gallery & Art Center by Stan Burnside is yet another mesmerising moment in time.Though we do not often think of slices of time, nor do we have the opportunity to enjoy those slices for their intense flavour and spicy complexity, we are far too busy trying to keep our heads above water, to enjoy the aesthetics of life. This is perhaps something that we overlook in our day to day grind and being ground, but in taking a few moments to explore Burnside’s most recent show at Baha Mar, and the first one to be held publicly in ages, (Burnside usually exhibits in personal spaces).

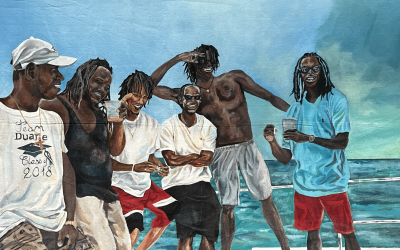

I would like to connect his complexity with the Creative Time Summit that is based in New York and streamed online on Friday, November 15th, at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. It is an opportunity to image futures differently.I want to pivot between Burnside’s ‘Ashanti Tow/A Shanty Town’ (2019 120 x 60” Acrylic on Canvas) and ‘Glyphing decolonial love through urban flash mobbing and Walking with our Sisters’, by Karyn Recollect. Her work offers ways of reading flash mobs in Toronto’s urban centre and their spatial taggings of possibility in what Recollect refers to as “creative acts of indigenous solidarity”. In Burnside’s work, can we explore the image as a spatial tagging that reveals an indigenous solidarity? Although not a flash mob, the space is a mob, or viewed as a mob. The un-deconstructed frame sends a message of alterity that is, that I perceive, as overlooked in Burnside’s strongly masculine gaze and image. The work is dark and abstract over a far more nuanced reading of spatial dynamics and the interstitial layering of historical presences or absent presences and total erasure. Burnside’s work, though this may easily have not been his intention because, as a viewer, I can receive a work of art totally independently or decontextualised from how the artists intended to be viewed. This is also more nuanced as we bring our own experiences to art and seeing that constantly individualises feelings and perceptions, which is so important in being human and in witnessing our truths.Each of our truths are uniquely tied to lives that are differently lived.

There is something very Picasso-esque about the work, yet it is uniquely Bahamian and offers so much of a history of African displacement in the New World and its overwriting, drawing, disappearance under the topicality of lush spaces, textured for misreading.

In Recollect’s work, she goes through a complex study of space and indignity and indigenous people’s resistance to erasure or their decolonial being that is seen in and their experiencing and claiming space. Though her work is far more complex than I make it out to be, I think it provides a glyphing space for imagining new futures. In this process we can imagine a glyph as an elemental symbol within an agreed set of symbols, intended to represent a readable character for the purposes of writing. In this case, I want to use it for art because Burnsides work has a number of symbols embedded in other symbols that work within the frame to provoke dis-meaning or disjunctured meaning. Such is the reading visioning of Ashanti Town/A Shanty Town for me. I find it overlaps with “Warrior Prince of the Misguided Youth Diaspora: Caught in the Crosshairs” (2019 60 x 80.5” diptych Acrylic on Canvas) where we once again see the glyphing that is not for writing but creates a great deal of other meaning. Burnside’s Cubism, in these images, is striking because it overlays so much meaning into another deeper level of image(ined) so that there are internal dialogues occurring between these two works. There may not be a flash mob, but there are certainly people who are present and strong, perhaps not seen or intentionally erased through epistemic violence and structural or state imposed violence that then leads to a culture of violence in these ‘Ashanti Towns/Shanty Towns.

The prevalence of these spaces in splendid isolation speaks a language of violence, that Recollect’s work sees in the attempted erasure of the indigenous peoples of Canada through state sanctioned and enacted epistemic violence. Their ‘corralling’ or displacement to reservations is like creating a disjunctured life of disappearances in presence. The act of removing to a space of alterity is significant and so the act of creating solidarity through spatial tagging or creativity is that much more significant. It is like the delimitation of the gaze that sees the Shanty Town as foreign, not for us, not inhabited by those of us who can no longer afford to inhabit the tropical space of marginal existence. The economic and cultural violence of disappearance is like the glyphing or cubism of life in works. Burnside creates a fantastic world within his cubist imagings of misguided youth (real, imagined or superimposed) and Ashanti Town. These are both real spaces somewhere, some grew up with the knowledge of them, others grew up with the memory of them and more grew up in their disappeared visibility.

There is something very Picasso-esque about the work, yet it is uniquely Bahamian and offers so much of a history of African displacement in the New World and its overwriting, drawing, disappearance under the topicality of lush spaces, textured for misreading. Perhaps this is too abstract but the enacting of beauty through displacement, erasure and epistemic violence, the imaging of possibility in Shanty Towns, already removed from the mainstream by an invisible-visible barrier that separates without bridging a way out; we see the black dispossession many African American scholars talk about and when they say that even educated African Americans are usually 90 days out of poverty. Martin Gilens explores this in “Race and Poverty in America: Public Misperceptions and the American News Media” Public Opinion Quarterly in 1996 and Moynihan (1965) creates policy in his work The Negro Family, yet the family and the racism of poverty or the fact that poverty is deeply racialised shows how dystopic paradise can be (Ta-Nahesi Coates, Edwidge Dantocat). The beauty and mastery of Burnside’s work is stunning, and so much more lies beneath the surface when we bring our own understanding to it. It is a tapestry of life lived after Dorian Inc. (2019) and social exclusion.

Cubism, glyphing and imaging for different futures where solidarity is not only possible but probable, likely is a message that issues from this fabulous work. This is much similar to the ideas in Carlos Rivera Santana’s ‘Aesthetics of disaster as decolonial aesthetics: Making sense of the effects of Hurricane María through Puerto Rican contemporary art’ which looks at the frame as being decolonial and art as being cathartic. The need to touch lives is clear after August 2019, and so many are doing so much. For me, it is simply serendipitous that Burnside’s slice of a moment could have occurred right after such devastation. How do we now bring more people into this space of re-imaging for solidarity? Burnside’s work illuminates so eloquently and magically the presences under the absences overlaid by mistaught and distorted visions.