By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett.

The University of The Bahamas

We are locked in bodies that demonstrate a temporal fixity that is only such. This became more apparent to me on my first experience in Salvador de Bahia, where the material remnants of slavery and colonialism remained intact and on view, unlike in New Providence where most of the remains of slavery are either dematerialised, vanished and decontextualised.

As “We Suffer to Remain” evidences, the coloniality of the postcolonial condition becomes even more poignant when expressed through a clash/confluence of arts. Art allows space for a dialogue that exposes the pasts and versions usually edited out by the passage of time, and the power of the state to redirect what was once empowerment discourses.

“We Suffer to Remain” provides an opportunity to discuss the eradication of slavery from Bahamian material history, and the loss of much of the local vernacular through disinterest and mindful erasure. We erect new palaces of pleasure where modernity and the imagination–unbridled by the local–exist in a liminal space like a boutique and ticky-tacky Miami.

The texture and materiality of this show resurrect the noise history and many narratives that have been erased, overpowered and written out of existence. As Rebecca Solnit states in her essay titled “Nobody Knows” of women’s stories of (s)exploitation and harassment: “these torrents of information come about as women’s status shifts back and forth between somebody and nobody, as people who’ve been silenced are heard”.

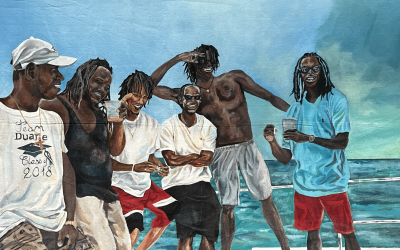

Installation shot of Sonia Farmer’s “A True & Exact History” for the exhibition “We Suffer to Remain”, a British Council supported project featuring the works of Graham Fagen, John Beadle, Sonia Farmer and Anina Major. The show runs through July 29th, 2018. All images courtesy of Jackson Petit-Homme and the NAGB.

Writers, artists, cultural advocates, intangible memory holders, and secret whisperers who visit us in spirit calling the names of generations of women and men whose memories we embody and in whose pain we languish without ever having experienced it directly, are a part of that resurrection. As participating artist Anina Major points out with her use of material, she wanted to, “explore how the harsh realities of slavery in reference to the body are evident today. Using materials that I think express the permanency, the fragility, the transparency, the depth, the underlying, the obvious, the dormant and the latent… To make work that spoke to human characteristics such as wisdom, empathy, endurance, strength and prudence in relation to pains of slavery, but approaching it with a sense of pure and raw beauty”.

Beauty is denied to many enslaved beings. Even after emancipation, we are taught that we are ugly. As the “Support the Puff” campaign demonstrates natural hair is beautiful, though denigrated. The trauma of slavery and marginalisation in this space can be likened to women’s struggle to be heard and seen. This article speaks almost exclusively to the experience women artists and writers have with asserting their voice over the silence of erasure.

In the essay above by Rebecca Solnit, she argues: “As a writer, I am someone whose job it is to hear and to tell the stories of the powerless. That status also means that my knowledge has power, so there is much that will be hidden from me”. As artists, the gathering of ‘We Suffer to Remain” create a similar dynamic where their job is to expose the hidden narrative, the overwritten text, some truisms that tourism and forgetting have erased so that the witnesses can begin to see alternatives to an official discourse of denial. Major notes:

I feel that for too long Bahamian history has been manufactured with an ulterior motive that denies our people of absolute truths and power. With my practice, I try to revisit that history that has been told to us with an investigative eye in hopes to clarify, analyse, (sometimes) mock and question some of the cultural symbols and practices we engage within society today. The goal is to learn from these observations and realise our ability to influence how today’s history is recorded.

This resonates on so many levels with us where the trauma of enslavement and post-slavery abuse and torture, social and political exclusion and deep segregation have damaged psyches. We are not affected because we choose to be, we are scarred because the trauma is denied, belittled, ignored through the erasure of material and silencing of the material past. The history of (s)exploitation and narratives of erasure have served to divide and to inflict more profound pain. Sonia Farmer puts it thus:

I consider my own writing practice a tool for disrupting and investigating existing narratives, forming a response that is not necessarily preoccupied with making new narratives to replace them, but rather exposing different narratives as a parallel, ultimately calling into question the inherent power structure in the existing narrative (such as historical accounts, folktales, mythologies, canonical books, etc). Experimental process of generation. . . are especially exciting opportunities to create direct responses to existing narratives by using [their] own language against itself.

Installation shot of Anina Major’s “Bessie’s Backbone” on view as a part of the exhibition “We Suffer to Remain”. All images courtesy of the NAGB.

As Solnit offers words on women’s place: “So often a man who believes that women have no voice is indignant when he discovers that someone is listening to them. It’s a struggle to own the narrative”. This must be said too for those survivors of former enslaved Africans, those who were brought here or who were forced to migrate like the Black Loyalists and the Black Seminoles.

“We Suffer to Remain” gives a nuanced reading to our cultural materiality and special existence in a space occupied by all those who have gone before but been erased by the deconstruction of history—the material past, as Edwidge Danticat notes “Misery won’t touch you gently. It always leaves its thumbprints on you; sometimes it leaves them for others to see, sometimes for nobody but you to know of.”

This show marks us. The artists demonstrate Solnit’s idea that: “The status of women [and Black people] remains in flux: sometimes, some of us are somebodies, people who can be heard; at other times, we are nobodies, silent and invisible. Perhaps all women are still categorically nobodies in some men’s minds”.

In our realities, we live the decontextualised pain of the past. Poignantly Danticat continues in the esteemable “Krik? Krak!” (1995), “No, women like you don’t write. They carve onion sculptures and potato statues. They sit in dark corners and braid their hair in new shapes and twists in order to control the stiffness, the unruliness, the rebelliousness.”

Danticat’s work–like Farmer and Major’s projects–is a testament to violations of the past visited on the physical bodies of those who remain. They are bold. They create dangerously, “Pito nou led, nou la!” We are ugly but we are here, and we make no excuses for how we disturb the discourse, own the narrative and re-empower the voices of our ancestors.