By Natalie Willis

Anyone who has taken the BGCSE Art in the past 20 years can perhaps agree with me when I say that if I never see (or paint) another seascape it will be too soon. It’s the picturesque gateway drug of art – along with the painfully ubiquitous local fruit still life – and we teach 16 and 17 year olds how to render these aspects of our Bahamian everyday and by design fail to teach them to question the history of these images. There is undoubtedly a joy in accurately technically executing a realist work, but it doesn’t teach us to see. These exercises don’t really teach us to question our landscape, why we know of local fruits but many of us don’t have these trees in our yards, why we have rarely tasted them, why we don’t have easy access to the isolated, private beaches we’re meant to portray, that apparently portray “Bahamian”. Or worse still, we show ourselves in a patronising stereotype of parochial island life – a centuries old image we still regurgitate.

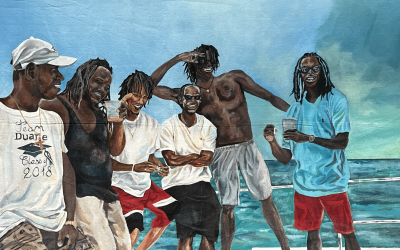

Mhudda, (1978), Jackson Burnside III, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48. Part of the D’Aguilar Art Foundation Collection.

Be it poverty-porn or the “smiling native”, the tropes of poverty around Black people are many, and those dealing with it in their lived experience are many still. It isn’t that the image itself is problematic or that it doesn’t hold truth, it is the framing. The everyday quality of Jackson Burnside’s Mhudda,1978 belies its clever and aware use of metaphor, far from the Bahamian mundane it shows. The late architect, artist, and avid Junkanooer gives us a scene that could be almost anywhere in the country. Seaside, men in boats, potcakes, a woman – the mhudda, screen doors, children, and a single lizard. This is the norm for many. The assumption being that this woman is looking after her children, and perhaps even those of neighbours dropping by, as is common for most of us growing up here who had the benefit of truly being able to engage in an open neighbourhood community.

Children from neighbouring homes find their way to the nearest matriarch, who, stern, kind or both, would often look after and feed them. So often we hear “it takes a village to raise a child”, but who raises us when the village is gone and replaced with city, hotels and offices? Where is the space for community when the space is gone and crime is prevalent? These are some of the questions stirred up by Burnside’s image.

Mhudda also gives us key information that illustrates Bahamian visual cultural references, and also highlights the fact we are losing this information. The several children and animals in the image, paired with the woman’s stern expression as she looks into the distance, make obvious certain things for us: she has many children to care for, and she is on her own (here) in doing so. The smallest detail, insignificant to someone outside of this region, is also one the of the most vital for delineating this image as Bahamian and Caribbean: the green lizard. The stories differ from island to island, and even person to person, but the connecting thread is the same: green lizards, whether they jump on you or they are present or you dream of them, they mean a baby is on the way. With this in mind, the story of Mhudda (1978) begins to flesh itself out. Is the woman staring off deep in thought because she is expecting another mouth to add to her sizeable, hungry brood? The men on the boat, are they missing in action in the home due to work at sea? The potcake mother and her pup with its ribs showing through, are they are a representation of Mhudda and her situation currently?

Mhudda, (1978), Jackson Burnside III, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48. Part of the D’Aguilar Art Foundation Collection.

It is the unfortunate conundrum of far too many Bahamians throughout our history. The work is erratic and irregular, and women – rather than choosing – are often relegated to the home and domestic duties. It is honorable work, but it is often thankless. But what is this mother doing, and where is she going? The ocean, painted in blue stripes, with the yellow sand beneath it, and the stoic, dutiful Mhudda and her dark skin center – Burnside paints the flag and this particular Bahamian story in one. Like the Black triangle of strength, she looks out to the distance, the future, and rather than shaken, she is determined. Women always find a way, but most of all so do mothers. It is something that Burnside clearly meditated on over the years, as a second painting, Mhudda II, 1982, further opened up his initial interpretations of the cult of domesticity and struggles of Black Bahamian women.

This work is so simplistic at first glance, drawing us in with the stylised representation, but then we dig deep and find our story told back to us in critical awareness of the state of the nation. Burnside is remembered as a passionate advocate for the arts in The Bahamas, and the current way of representing ourselves visually in schools, the way we actively teach a lack of engagement with our issues and culture in favor of the picturesque – it does us all, and not just his memory, a disservice.

Mhudda (1978) is on view as a part of the current Permanent Exhibition at the NAGB, “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean”, dissecting the way language (visual and verbal) shape The Bahamas. The Permanent Exhibition is open through June 2019 and as a reminder, the NAGB is free and open to locals and residents on Sundays from 12 – 5 p.m.