By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

Colonialism sounds romantic somehow. Alongside Victorianism, it seems to speak of stories and tales of old. Given that from the age of Elizabeth to the Georgian, the Caribbean was captured in a definitive enclosure along with many other colonies around the world. We have not been liberated, concepts of beauty, ownership and empowerment seem trapped in hidden spaces beyond the national imagination.

Art, however, challenges us to unseal these traps and to think about our beauty on its terms, without the complexity of colonial desires and occupational hazards. We see the dawning or the ebbing of empire as something to be proud of and if anyone chances to challenges that perception they are rebuked. It is not just about being royalists in a country that was raped and pillaged and then ‘civilised’ through the force of civility, but that we were not good enough to civilise ourselves. In the French colonial experience it was referred to as assimilation and in Belgium called brutality, a native.

Power Girl (Incarceration Queen), 2018. April Bey, “African” Chinese knock-off wax fabric, hand-sewn into canvas with drawing ink, Chinese knock-off pearls, made-in-China thread and needles. 72” x 48”. Images courtesy of the artist.

Colonialism had a particularly damaging relationship with gender as it painted an ideal of the Madonna or emasculated negro, happy to serve but always just beyond salvation. The Madonna, whose beauty was not available to Black women has served as a whipping post for colonised femininity for decades. Though derided for not being good enough and being jezebels, vixens, workhorses or whores, Black women were used to exploit their people and to undermine their power, while Victorian womanhood was exclusive and built around white purity. We can see clearly in April Bey’s “Power Girl” series that is called into question. The art of the late Victorian and through the second Elizabethan age, beauty was particular, constrained or built around whiteness, exclusive of the thicker-lipped, rounder figured and full-busted beauties.

Victorianism was a period of defining Englishness in contrast to otherness. Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria become symbols of Englishness, strength and virtue. Queen Elizabeth II embodies this legacy as she symbolises untouchable feminine beauty and Victorian ideals of virtue. She represents whiteness locked in the British crown that was exported to all corners of the imperial world and then re-imported to Britain under “colonisation in reverse,” as Louise Bennett– aka Miss Lou–Jamaican poet and performance artist presents. At home, however, something was still amiss. Art was trying to struggle free of the self-hatred fed by colonial inferiority programmes, it then found a voice, but nationalism and politics remained stuck.

Los Angeles-based Bahamian artist, April Bey’s work, challenges the reductive and controlling nature of Victorian imaginary as it relates to femininity and exclusivity. The mythology, imagery, and manners are certainly controlling metaphors for colonial space and relations. In Bey’s wall hangings interrelations between the two types/moments of colonisation in Bey’s work; the juxtaposition of a Chinese takeover with British remnants. The time and context, as well as method and mode of contact, may be different but the result is similar.

“Chinese knock-offs,” as Bey terms them, have swamped markets internationally and cheapened many national brands so that other nations cannot compete with the real thing anymore. As cheap Chinese cloth displaces authentic African fabric questions of cultural authenticity, appropriation and erasure raise their heads. In the Caribbean, similar to Africa, art is captured by the displacement of local space not through war or hostile takeover, but through a trojan horse investment that has removed all entry ports and coastlines from public space.

“Power Girl” is a play on imagery and reality that leaves the colonial woman in a deconstructed depreciated position. Bey states:

“The Queen is depicted with bars of hand-sewn fabric that were purchased in West Africa, and that is marketed as “authentic” African fabric but in reality is just Chinese knock-off fabric sold due to the “authentic” fabrics costing too much for the actual people to afford. Hung around her neck is knock-off Made-in-China pearls referencing the obscene levels of wealth the crown carries while at the same time alluding to the Chinese hidden wealth through their knock-off industries built on slave wages”.

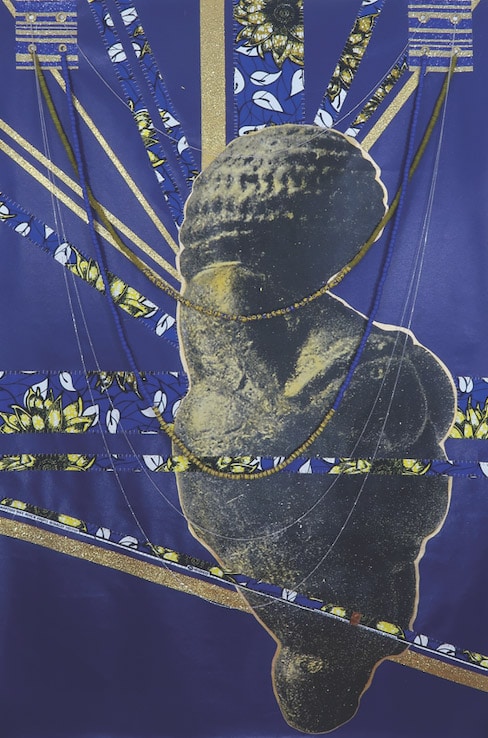

In contrast, is the Venus of Willendorf—an anonymous woman (icon) and yet representing an Asante Queen. Around her neck hangs truly authentic beads from Kumasi, Ghana—the Asante region. The Asante are recognised as winning the war against the British colonisers in unique ways and uniting several tribes against one enemy—a first in this region.

April Bey Power Girl (Asante Queen) 2018. April Bey, “African” Chinese knock-off wax fabric, hand-sewn into canvas with drawing ink, glass beads from Kumasi, Ghana. 72” x 48”. Images courtesy of the artist.

To appreciate the beauty of Africa, one must see it without the colonial underpinnings and trappings. To understand the realities of poverty, one must tear down the colonial façade of civility and see the exploitative scaffolding of the empire(s) hidden behind it. As seen in HuffPost’s “Britain’s New African Empire,” (2016) and the exposés on Chinese investment in Africa and the Caribbean, from ports to mines and stadiums, colonialism is still deeply embedded in most of the former-colonised world. To honestly see Black beauty, one must see it without the occlusions of colonialism; the constructs of civilised beauty or working towards deconstructing imposed beauty, while celebrating natural, wild, unabashed and dynamic ranges of beauty.

Today, despite claims of Black majority rule and being a proud Black nation with Black beauty, today the acceptance of natural Black hair is limited. Schools still require students not to wear their natural hair untreated or ask them to tame it. Employers still request that their sales clerks not wear natural hair exposed as it will turn off the shoppers. So, as much as the coloniser has been replaced by yet another “colonial” power and the limits of Bahamian space moved inward, respectability and social politics reinforce these power dynamics and shun those who refuse to conform.

Bey’s work while juxtaposing Chinese and English colonialism deconstructs the restrictions around seeing the beauty and power of Blackness and Black femininity. It is a work that speaks to continued exploitation of a continent, rich in natural wealth and resources, but poor because of the geopolitics of history and development.

It also shows the complexity of the colonial relationship and how deeply it is invested in and internalised in the Caribbean as we continue to look to our oppressors for liberation. The work is disarmingly pretty and approachable, but it narrates a reality of complex relations hidden behind that façade of post-colonial “independence” mired in debt and systemic dependence.

Bey’s work will be on view at the NAGB as part of the 9th National Exhibition, “NE9: The Fruit and The Seed” through Sunday, April 7th, 2019.